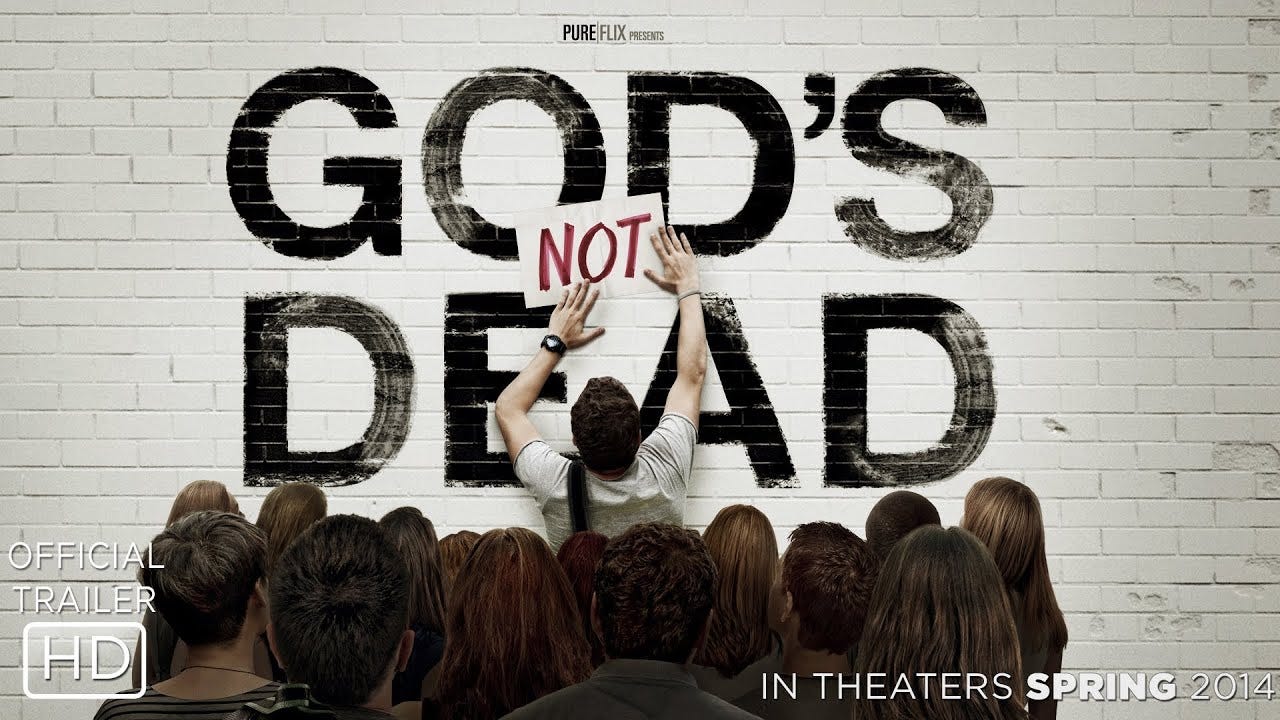

Some of the biggest fans of the hit evangelical series God’s Not Dead are radical leftists. So much so I’ve often wondered whether PureFlix has subversively marketed to the Jacobin crowd under the radar. YouTube is full of Breadtubers who’ve watched and deconstructed the series every which way from Sunday, even making sure to keep up with the story as it goes on in true fan style. Some of this is undoubtedly just the perverse joy a lot of us smug leftists get out of hate watching bad movies (see Tommy Wiseau’s The Room for the gold standard) made by right-wing fundamentalists, ironically evidencing the condescension resented by the filmmakers. Though in fairness, they are in the last position to cast stones at the left for not taking alternative political viewpoints seriously.

I’ve recently finished going through all five of the God’s Not Deadiverse films, starting with a long overdue rewatch of 2014’s OG and ending with 2024’s appropriately election heavy God’s Not Dead: A Light in the Darkness. They are a lot of hammy fun, though very much unintentionally. At least some of the fun comes from seeing a who’s who of 90s TV stars like Kevin Sorbo (Hercules), Melissa Joan Hart (Sabrina the Teenage Witch), Dean Cain (Lois and Clark: The New Adventures of Superman) and John Corbett (Sex and the City weirdly enough). Of the quintet (and counting) only the third God’s Not Dead: A Light in the Darkness approaches being of mid made for tv movie quality. This is because it is the only film that has something like recognizably Aristotelean characterizations, where by now series lead Rev. Dave Hill confronts both external hardships wrought by the secular world and internal difficulties resulting from his own flaws—-in particular, failing to get along with his amiable atheist brother Pearce Hill, and confusing his own attachments with the good of the Christian community. It’s a long way from G.K Chesterton, but relatively inoffensive.

The other films are by and large unrepentant fundamentalist propaganda that struggle to outdo the last in intensifying their persecution complex and taking extremely broad swipes at the secular world. Even Matt Walsh, in his itself very superficial book Church of Cowards, makes fun of them. He described God’s Not Dead I as “possibly the most torturous thing a Christian has constructed since the Inquisition” because it “insults its audience’s intelligence, demonizes the outside world with cult propaganda, forgoes authenticity for emotional manipulation, and does it all under a slick, Jesus-y veneer.” I couldn’t have put it better myself beyond adding God’s Not Dead I was the most torturous thing a Christian constructed since the Inquisition until Lady Ballers was inflicted on the world.

Nevertheless I agree with Zizek that there is always something to see in any work of art, sometimes most especially those that make no effort or perhaps just have no aptitude at concealing their ideological impulses. This is why it is worth looking a little closer at what makes the God’s Not Dead films so myopic that even a self-described “theocratic fascist” like Walsh feels compelled to look away. It can tell us quite a bit about the reactionary worldview in its most distilled form.

Quid est Veritas?

I mentioned that of the quintet only the third comes across as anything like a real movie. This is because Rev. Hill is not only driven to doubts about his role in the increasingly hostile external world and how to work within it. Instead he very gently questions, if not his core convictions, at least some basic attitudes towards atheism and secularism as embodied by his likeable and helpful brother. The movie ends with him growing somewhat as a person through self-reflection on his priors, which helps him become a better sibling and reverend. Not exactly Graham Greene, but largely inoffensive.

Every other movie is structured very differently. The main characters never seriously question their core conviction that Evangelical Christianity is undoubtedly correct. And even when they are sometimes shaken, a quick chat with a fellow believer rapidly helps them see they were of course right after all. The extreme one-sidedness of this is relentlessly demonstrated by the enormously caricatured portrayal of secularists, atheists, liberals, Big Business, and “socialists” throughout—-who are sometimes literally portrayed as being aided by Satan. The two worst offenders in this regard are the bookending films.

In God’s Not Dead I, college student Josh Wheaton takes a class with philosophy professor Jeffrey Radison, who orders them to immediately write “God is Dead” on a piece of paper because great minds from Noam Chomsky to Richard Dawkins insist that it is so. Wheaton refuses and Radison, who must be tenured beyond limitations, decides to publicly challenge his first year student to a series of debates after which the class will judge. Despite being confronted by a few softball-atheistic arguments lobbed by Radison, Wheaton never doubts he is right and eventually prevails over Radison (who you’d think would know a little more about how to respond to very basic theistic arguments given his specialization.

In God’s Not Dead V, our good friend Rev. Hill returns and decides to run for public office. He’s up against returning nemesis Pete Kane, who apparently both wants to institute socialism via Medicare for all and has the support of Big Business. Kane is an even more mustache-twirling and unrepentant villain than Radison, and loves nothing more than insisting a good Christian should support social programs that help the poor while also defending a secular approach to morality. At the end, Rev. Hill triumphs in debate by pulling the meme, and insisting he’s tired of being lectured to by non-Christians who weaponize a few verses of scripture to argue for liberal causes while trying to banish Jesus from the public square. Kane’s bad faith point about the immanent Christian case for a better economy is sidestepped.

My point here is not to pick on the bad and straw-manning arguments developed in the films. It’s instead to highlight what they represent. One of the reasons the characters are incapable of fundamentally growing or changing is they are abjectly and confidently dismissive of any and all calls to reflect deeply on their own worldview. Indeed any such calls are taken to be made in bad faith or are presented as intrinsically hostile, and so require confrontation rather than dialectic. Each film in microcosm is therefore not so much a defense of evangelism as an affirmation of it, and a call to banish uncertainties in the name of dogmatics.

Ironically, the affect of all this is to make the movies come across as exceptionally arrogant. Arrogance that comes cloaked in humility; doubling and tripling down on unearned certainties defended because they are consoling. The ego implied by such an attitude is displaced—-but in so doing is also intensified—by ascribing its source to God himself, whose desires the protagonists have a privileged understanding of, which in turn entitles them to a level of righteousness rarely seen in art. I’ve seen Aaron Sorkin films that better display a modicum of Christian humility (though that is, without a doubt, purely by accident).

I’ve written before about how many on the right privilege an affect of certainty over a fallibilistic approach to the truth. While not a vice in itself, an intense emotional need for metaphysical certainty can become a positive barrier to truth insofar as it leads one to accept pieties on the cheap rather than earn convictions through consideration of their plausibility to others. All this reaches a level of egomaniacal intensity in God’s Not Dead that is extremely rare and spiritually problematic. Precisely through so insistently banishing the specter of spiritual and metaphysical doubt, the movies convey a sense of religiosity that has been earned on the cheap. Whatever struggles one has with faith arise only from the need to convince a yet unconvinced world that you know what is true and right and it is time for them to come on board for their own sake.

The Joys of Victimization

All of this feeds into my core quasi-Nietzschean point about the relationship between the affirmation of unearned certainties and the persecution complex displayed in every one of the films. Each one presents the evangelical Christian community as an object of intense hatred and hostile interest by the secular world, which never misses, however petty, an opportunity to fuck with Reverend Hill and his flock. It’s said that many an accusation is a confession and that is very much the case here. The faux humility displayed by rote invocation of Christian pieties is perennially belied by the presentation of evangelicals as victimized precisely because they are in possession of righteous truths the world simply must deny. If they affirm anything, it is Nietzsche’s assertion that the failure to instantiate a belief in one’s own definitive superiority can be sublimated into a victimization narrative, where the world wishes to destroy you precisely because it cannot abide your holy goodness.

This immensely self-flattering narrative aligns with Angelia Wilson’s recent The Politics of Hate: How the Religious Right Darkened America’s Soul, where she characterized the Religious Right as firmly convinced of its own moral superiority and very willing to insist upon that. Seen this way, the sense of ubiquitous victimization conveyed in the God’s Not Dead films doesn’t come across as a Christlike willingness to die even for the good of one’s enemies. Instead, it comes across as a sneering conviction that the morally inferior world of liberal enemies is intensely and sleeplessly trying to displace the religious right of what is rightfully theirs: their country governed by their people and their values. Indeed the “redemption” arc of deathbed converts like Professor Radison or abusive Muslim men like Misrab in God’s Not Dead IV indulges a fantasy where the irreligious and heathen will come to see the truth evangelicals already know. So many of the films come across as cinematic equivalent of adolescent debate bro revenge fantasies, where smug liberal intellectuals and influencers are put in their place by perfect riposte after perfect riposte and the audience literally cheers for our wholesome protagonists.

Conclusions

There is nothing that says Christians cannot produce truly extraordinary films. Martin Scorsese’s The Last Temptation of Christ remains my favorite movie ever, and his more recent Silence is a remarkable mediation of the actually-trying sacrifices Christians might be called to make. What makes both edifying is how seriously they take the spiritual mission—-in this case seriously enough to follow the Christian Platonist injunction to question even the truth of Christianity, if that is what is called for, to better understand God’s creation.

What makes the God’s Not Dead films so offensive is not that they defend Christianity, which can and has been a catalyst for some of humanity’s most noble enterprises. What the God’s Not Dead franchise does instead is insist on Christianity, which is another way of saying they don’t take it seriously enough to even bother defending it.