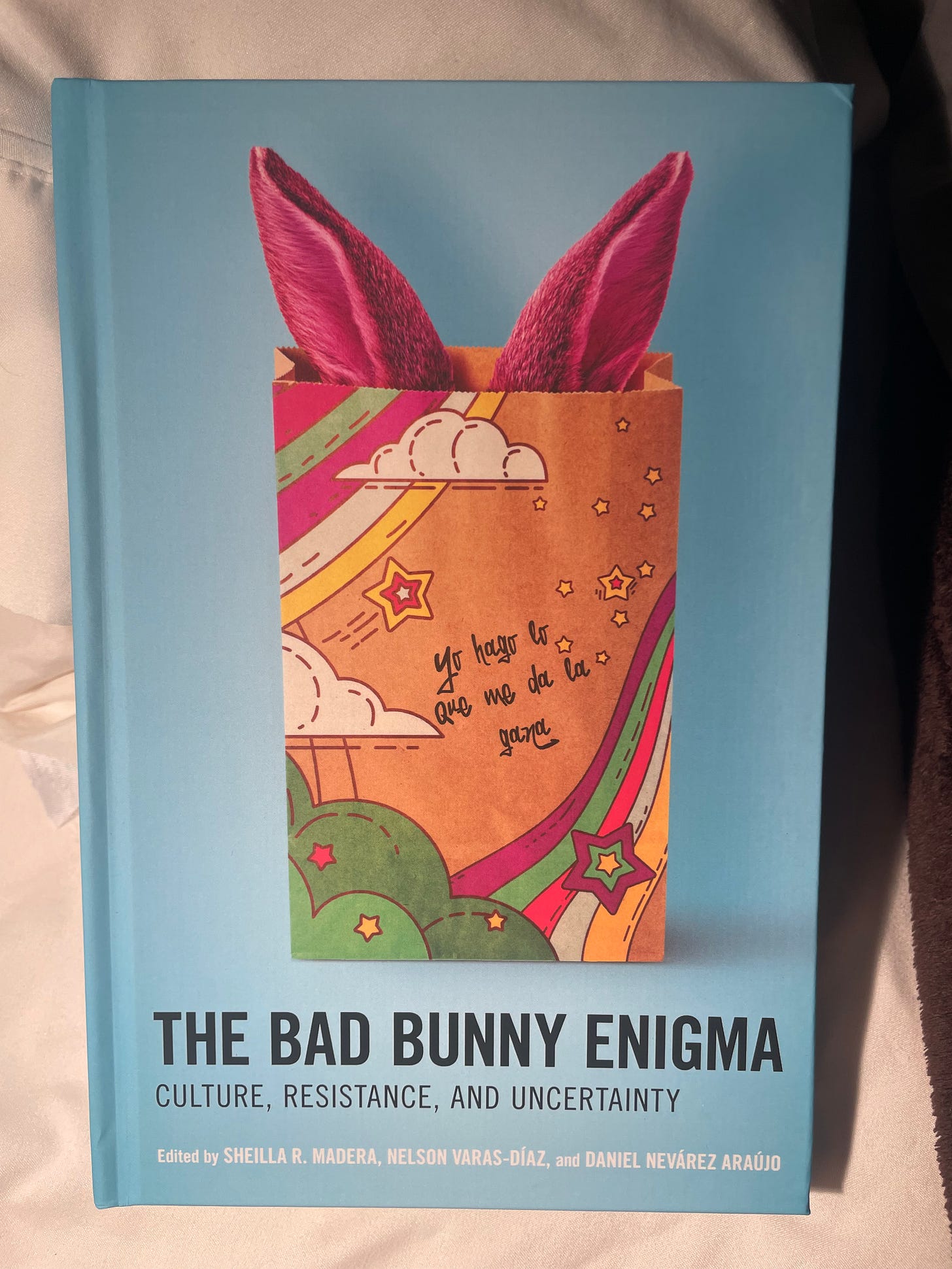

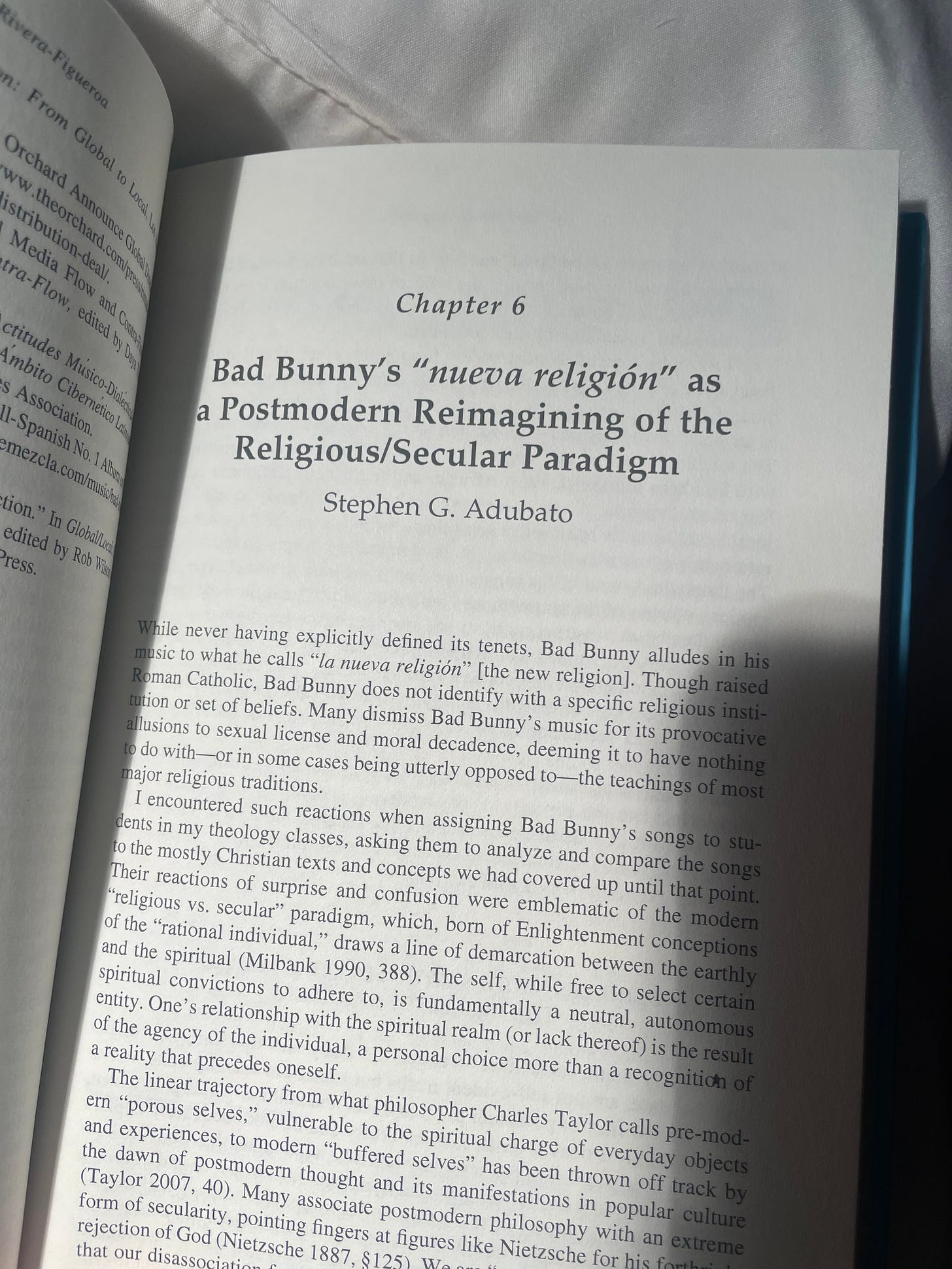

No, we’re not gonna review ‘DeBÍ TiRAR MáS FOToS’…at least not now. Instead, we’ll leave you with an excerpt from Stephen’s chapter in the new book The Bad Bunny Enigma: Culture, Resistance, and Uncertainty, published by Rowman & Littlefield.

You can also check out Stephen’s Bad Bunny content at Law & Liberty, Nylon, America Magazine, The Federalist, Substack, and the Hispanic Theological Initiative.

While his music has propelled him to the top of Spotify’s global end-of-year chart three times, a good deal of Bad Bunny’s fame is indebted to his public persona. Moreover, the ethos of the “nueva religión” is expressed not only through the cosmic imaginary of Bad Bunny’s songs but precisely through this public persona. A master of the spectacle, his performances, social media posts, merch, and offstage outings have garnered the public’s fascination to the point that the media can’t seem to stop talking about him.

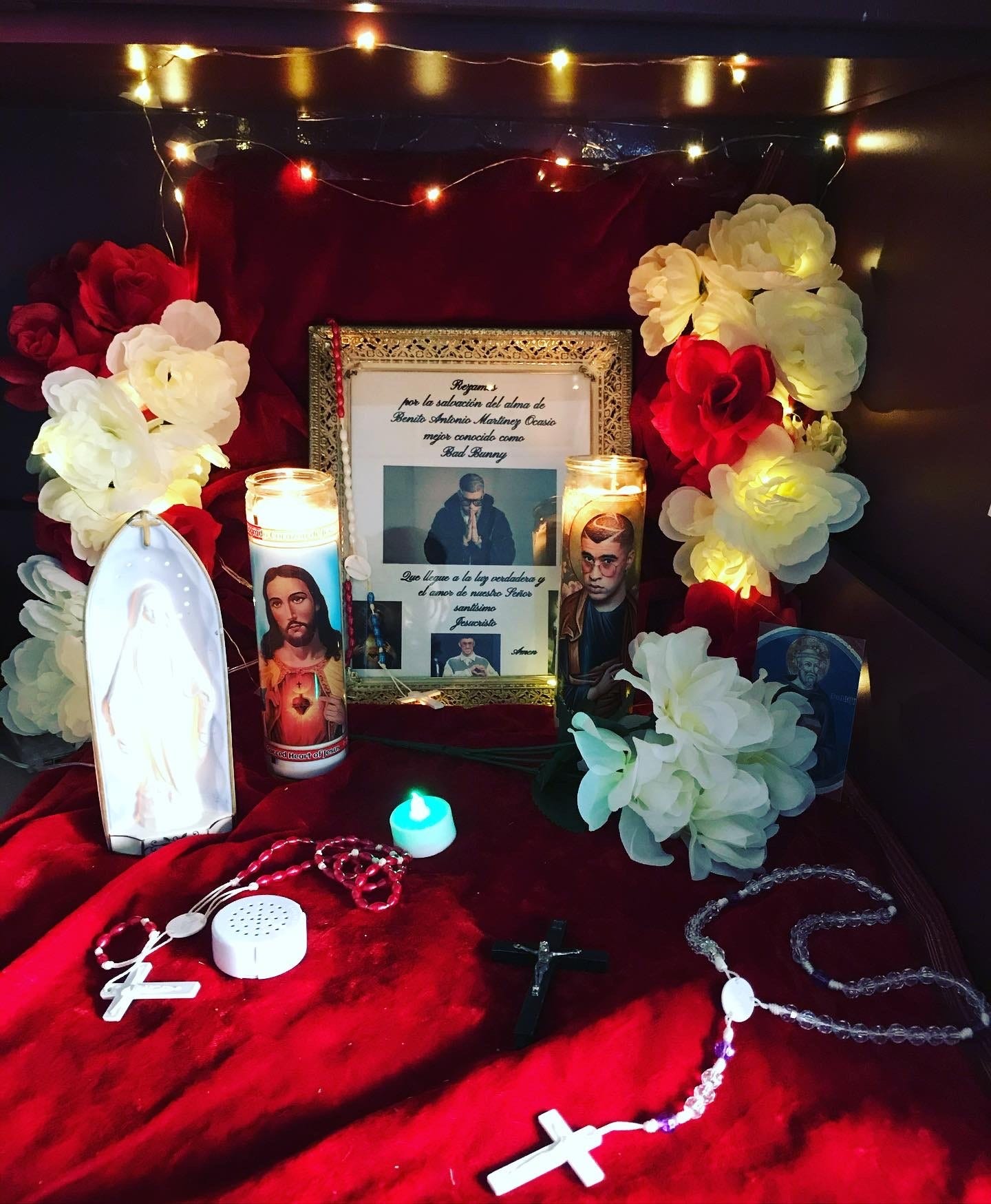

The way his performative genius captivates the public’s attention implicitly deconstructs and comments on—albeit in a subtle, oblique manner—the notion of the modern buffered self. The aura surrounding his public image is a manifestation of the contemporary cult of celebrity, which—whether we are cognizant or not of what the term literally implies—is a matter of worship. The pantheon of musical idols in today’s culture indicates that, contrary to the naive assertions of modernism, we are hardly living in a “neutral” secular sphere. Thus, our identities and agency are more porous than we may realize. Bad Bunny’s pervasive and iconoclastic public image speaks to the tendency of postmodernism to debunk such anthropologically naive modern constructions. Furthermore, it provokes us to reassess our perspectives on ourselves and the world we inhabit, challenging whether it is truly us who shape the narrative through which we see these realities.

To say that Bad Bunny has “gone viral” is a drastic understatement. His omnipresence on our feeds is further bolstered by the reposting on the part of both fans and critics alike, who seem always to have something to say about him. His frequent cross-dressing and fluid sexuality are only the tip of the iceberg.

…

Let us further examine the deeper implications of Bad Bunny’s performance of gender stereotypes, much of which operates within the Caribbean paradigm of machismo—which he simultaneously conforms to and defies. This paradigm holds that men not only must distinguish themselves from women but must do so by demonstrating their dominance over them along with projecting their sexual prowess. The patriarchal charge of this paradigm carries with it an aversion to homosexuality and gender cross-identification as diminishments of one’s masculine persona. Perhaps his least viral form of gender-bending is his inversion of the male gaze in his songs. Many critique the male gaze for objectifying women for the sake of male pleasure and dominance. But in songs like “Andrea,” “Yo perreo sola,” “Solo de mi,” and “Callaita,” Bad Bunny allows his fascination with a woman to take on a reflexive effect in the form of speculating about her life story and trauma, even allowing himself to be objectified and manipulated by the allure said woman has over him. We are left to ponder the nature of identity and who or what truly has the power to define us, as if Bad Bunny is hinting that this power lies in the hands of whoever can most fully capture our attention.

…

There exists a chasm between the actual substance of Bad Bunny’s career and the spectacular “hype” surrounding it. The society of the spectacle culminates in the cult of the celebrity, in the exaltation of godlike figures who pervade the collective consciousness. The hype and the reverence surrounding these celebrities often have little to do with the substance their work offers (assuming they do have something substantial to offer). But what exactly are we looking at? Does what attracts us to the hype have anything remotely to do with the concrete, pragmatic needs of our quotidian affairs?

Enlightenment humanism holds that reality itself is not charged with any substance in itself nor any intrinsic meaning of its own (Schindler 2017). Subsequently, buffered selves are afforded the agency to impose meaning onto objects. This separation between substance and reality is what philosopher David Schindler Jr. calls the “diabolical” tendency of modern freedom. Dia-balo, “to separate” in Greek, is the polar opposite of the symbolic sym-balo, “to put together” (Schindler 2017, 151). To call the modern conception of autonomy “diabolical” may sound far-reaching. Yet, the false assertion that individuals can truly live as autonomous, self-interested, buffered selves often comes with sinister consequences.

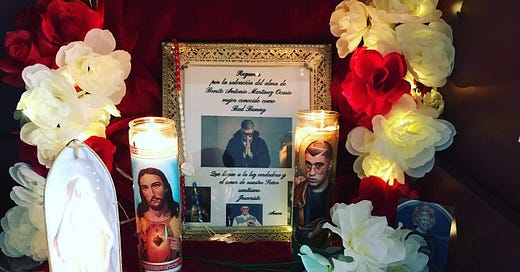

The illusion of neutral secularity is shattered by phenomena like the cult of celebrity, which, as theologian William T. Cavanaugh describes it, embodies a “migration of the holy” (Cavanaugh 2020, 70). Echoing Marx’s theory of commodity fetishism, Cavanaugh insists that the “holiness” of a given object “migrates” or is transferred elsewhere. Though we are told that spiritual forces lie outside of the neutral secular realm of self-regulating individuals, we inevitably confer a sense of enchantment to realities that have little (or a negative) value in themselves. The mystical aura surrounding the experience of purchasing a product is what has allowed companies like Amazon to capitalize on customers’ desire for spiritual fulfillment, while underpaid and abused workers must face less than “enchanted” circumstances—thus the irony of Amazon’s “Fulfillment Centers” (Cavanaugh 2020).

Similarly, musical artists are signed to major labels by corporate elites with little consideration of their actual musical talent and instead are groomed to be demigods who are capable of winning over the attention (and bank accounts) of the masses. This lack of regard for substantial artistry results in the further empowering of elites, while the signed artists are often taken advantage of and manipulated, and other artists with considerable skill but who are less “hype-worthy” are left with few opportunities to build a lasting career.

Who, then, defines Bad Bunny’s public persona? More importantly, who defines our sense of identity as individuals—from our taste in music to our lifestyle choices—and the narrative that surrounds our sense of what is real? It turns out our world may not be as disenchanted as the Enlightenment thinkers thought it could be. Consequently, we may not be as free as we tell ourselves we are. Hidden, “mystified” elites assume a deific power to fill in the vacuum of modern disenchantment. In the end, they turn out to be the only ones who can actually “hacer lo que les dan la gana” (i.e., do whatever they want).

Through the lens of these larger questions about public spectacles and the power of those who lie outside of our field of vision, we can better understand the ways Bad Bunny experiments with subverting gazes and perspectives in his work. His frequent reference to checking if his love interest viewed his Instagram story forces us to ask if the identity we construct for ourselves is truly our own or if it is swayed by the power of someone who is “virtually” present. Among his many songs that invert the male gaze, the video for “Callaita” offers a provocative visual that further causes us to question what draws our attention and why.

His love interest holds up a mirror that reflects the sun’s light toward the end of the video (Bad Bunny 2019). It is as if she is challenging us to ask, “Who do you think I am, and why are you looking at me? Who is it that really controls the narrative of how you perceive me . . . of how you perceive yourself?” When I check my phone and see Bad Bunny appear in my Instagram feed and like the post or share it to my story, do I look into the mirror and ask myself why I am drawn to him? Is it pure hype, or is there something here of substance that impacts the way I look at my own life?

Further, can we truly claim to live as buffered selves? When we blatantly ignore our inherent porousness, we make ourselves vulnerable to the control of others who may not have our “fulfillment” in mind. When Bad Bunny incorporates imagery from the occult and esoteric rituals, is he merely following current trends in pop culture? Perhaps it is the case that he is trying to communicate something about the true nature of the music industry.

There was an article in The New York Times Arts section either yesterday or Tuesday about Bad Bunny. I didn't read it, but I think part of it was done in an interview kind of style.