Read the full article at The American Spectator

On Juneteenth, I decided to celebrate the day by visiting the Metropolitan Museum of Art. The Met currently has a variety of fascinating exhibits on display, including the Afrocentric Before Yesterday We Could Fly: An Afrofuturist Period Room, The African Origin of Civilization, and Juan de Pareja: Afro-Hispanic Painter. Earlier that morning, I had published a piece for Newsweek arguing that “conservatives” (basically referring to people who aren’t very “woke”) need to come around to embracing Juneteenth and taking concern with the reality of systemic racism.

I argued that while poststructuralism—which currently has a monopoly on race-related discourses—is very quick to reduce racial justice to mere abstract identitarianism and mechanistic analyses of power imbalances, this doesn’t necessarily mean systemic racism doesn’t exist. Those with traditional values ought to be concerned about systemic racism not for some moralistic reason, but because it destroys black communities and families’ capacity to take responsibility for themselves and contribute to the Common Good, as well as deteriorating their cultural roots—on an aesthetic and spiritual level.

Thus my satisfaction upon visiting the Met later that day: the exhibits presented fairly nuanced conceptions of racial identity that weren’t purely identitarian, and didn’t indulge in self-serving, blasé virtue signaling. They were comprehensive, capturing the rich cultural legacy of the African diaspora while also drawing attention to certain pragmatic matters of social justice. But I was most impressed by the exhibit on Juan de Pareja, which placed a strong emphasis on the importance of recovering one’s roots and traditions in order to discover one’s true identity (as opposed to identity as self-determined), as well as the role of aesthetics and spirituality in race relations.

Juan de Pareja was born in southern Spain in 1606. Of mixed ancestry (Spanish, African), he was enslaved by the renowned Spanish artist Diego Velasquez for nearly twenty years. Upon discovering de Pareja had a knack for painting, he decided to begin training him. After emancipating him in 1630, de Pareja went on to paint a series of well-received paintings, including his most famous “The Calling of Saint Matthew.”

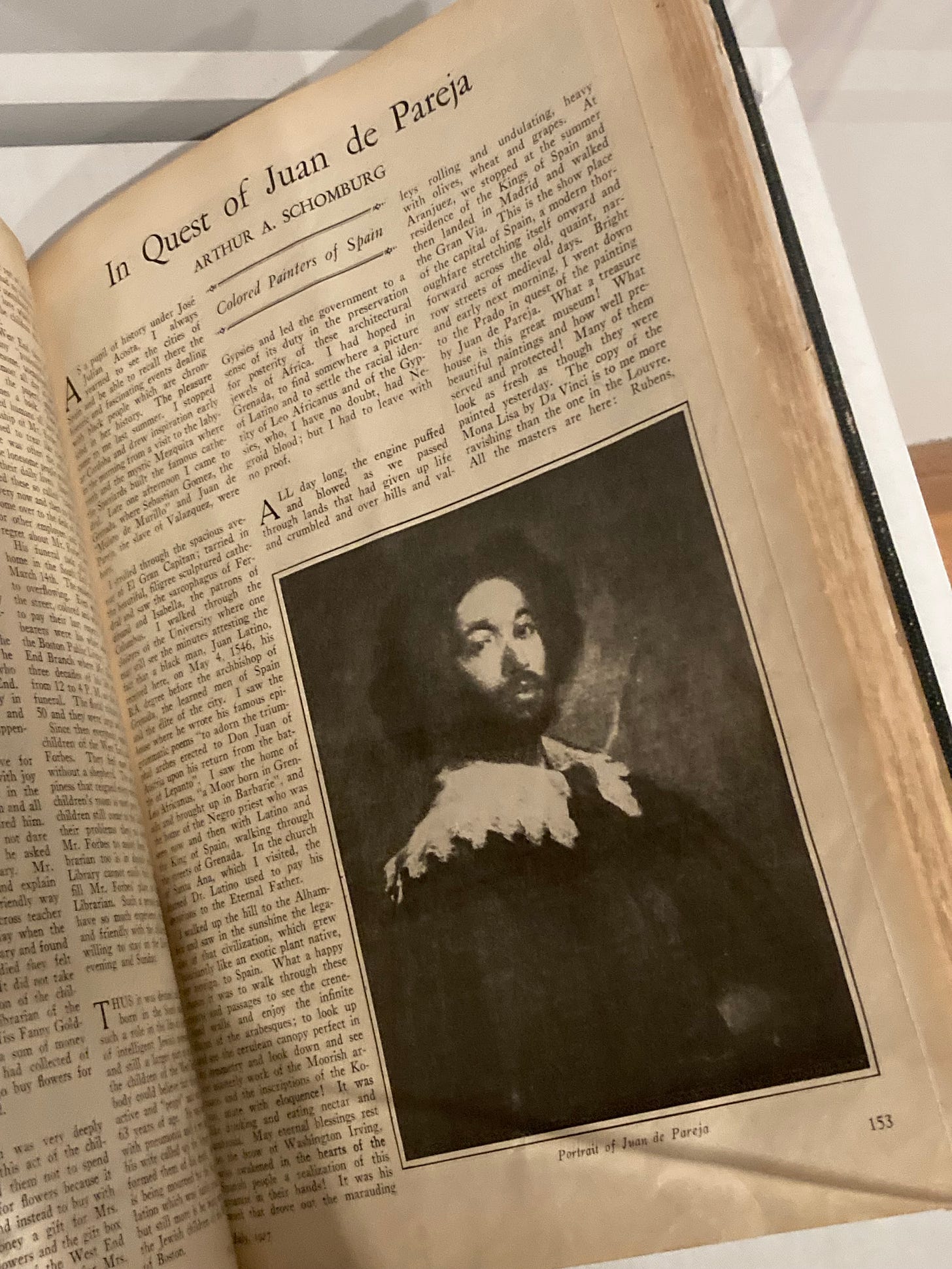

What’s most remarkable about the exhibit, however, is the inclusion of a component about Arturo Schomburg and his discovery of de Pareja’s work. Schomburg (after whom the Harlem branch of the NY Public Library is named) was a writer, historian, and activist who was born in Puerto Rico in 1874 to parents of Black and German ancestry. When studying in elementary school in Puerto Rico, “he asked a teacher when would they get to learn about Black history? And the teacher told him there was no such thing. That Black people didn’t have a history.”

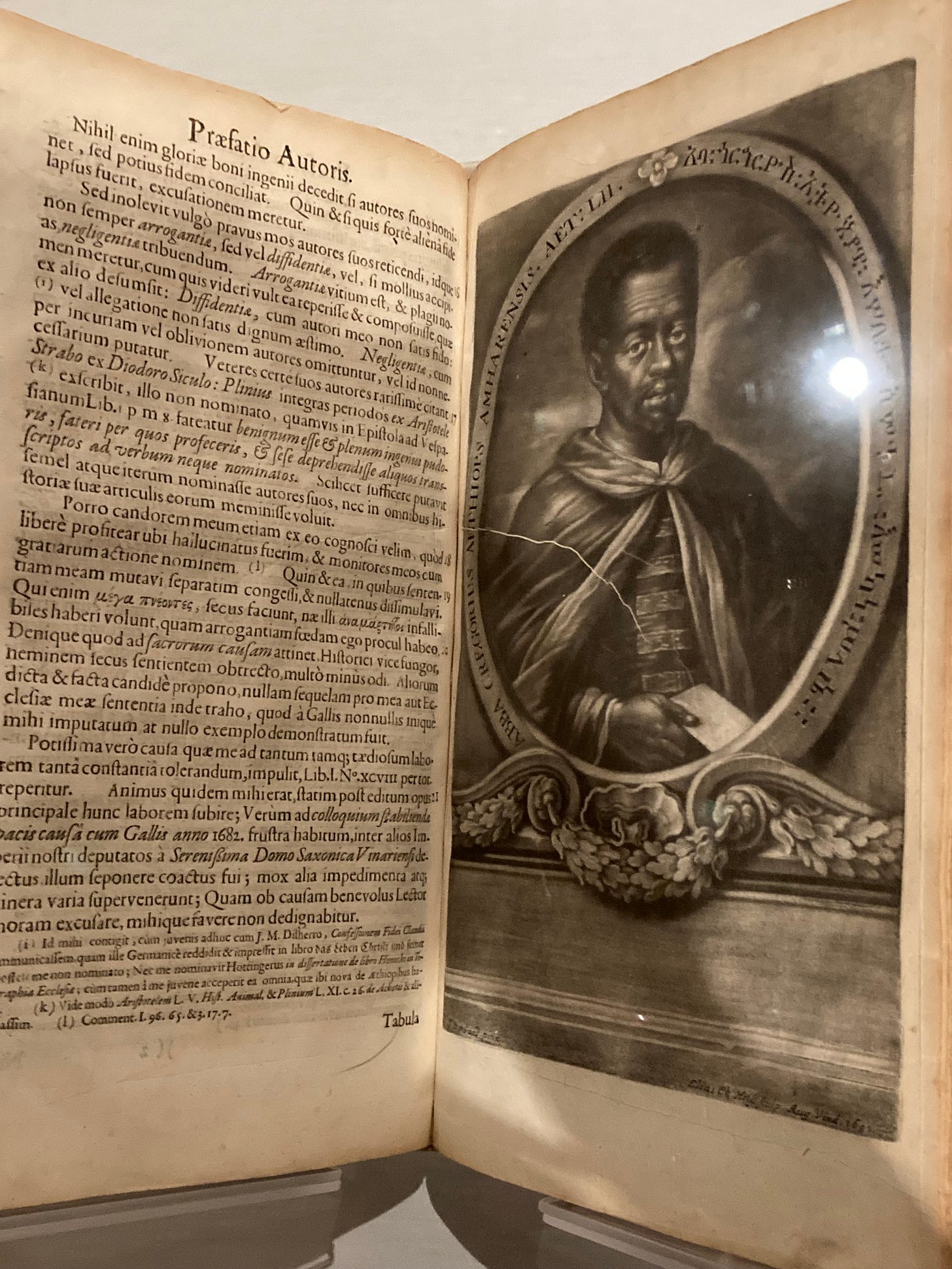

This answer spurred him to embark on a lifelong journey of uncovering the history of his roots, eventually going on to co-found The Negro Society for Social Research. While visiting Seville, Spain, he learned about the extensive history of Black enclaves that have persisted in the city, as well as others in the south of Spain, among whom were figures like de Pareja, Leo Africanus, Sebastian Gomez, Diego Ortiz de Zuniga who contributed works of art, theology, and history.

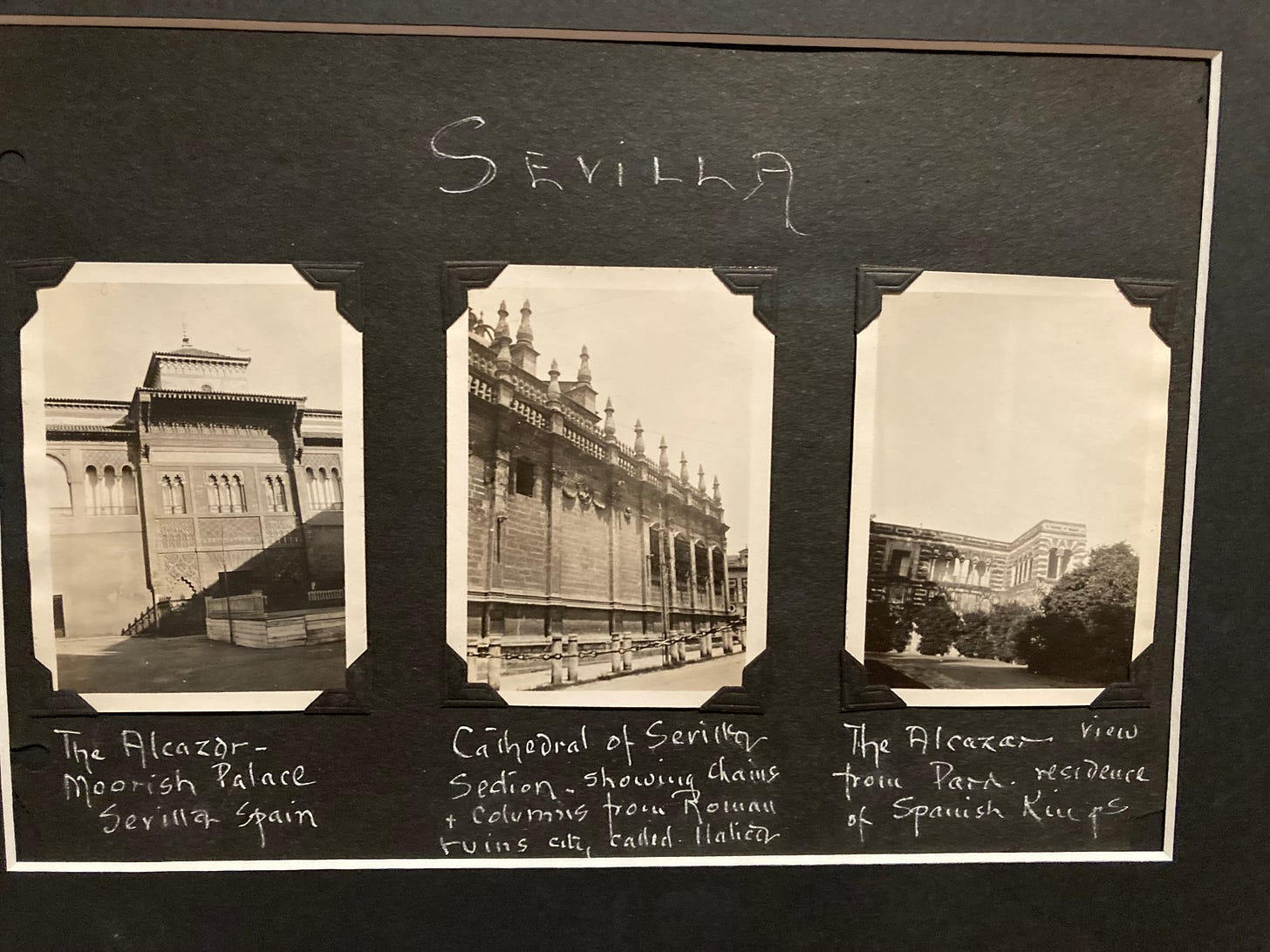

For Schomburg, discovering the existence of such communities, and the works they created, shaped his sense of his own identity, filling him with pride and dignity (which he vividly describes in his essay “In Quest of Juan de Pareja”). Thus his sense of mission when returning to the Americas to not only create more educational and economic opportunities for descendants of the diaspora, but also to forge meaningful communities that were spiritually nourishing and connected people to their rich histories—which had been deprived of them by the slave trade and racism. Schomburg wrote:

The work our race students now regard as important, they undertake very naturally to overcome in part certain handicaps of disparagement and omission too well-known to particularize. But they do so not merely that we may not wrongfully be deprived of the spiritual nourishment of our cultural past, but also that the full story of human collaboration and interdependence may be told and realized. Especially is this likely to be the effect of the latest and most fascinating of all of the attempts to open up the closed Negro past, namely the important study of African cultural origins and sources. The bigotry of civilization which is the taproot of intellectual prejudice begins far back and must be corrected at its source. Fundamentally it has come about from that depreciation of Africa which has sprung up from ignorance of her true rôle and position in human history and the early development of culture. The Negro has been a man without a history because he has been considered a man without a worthy culture. But a new notion of the cultural attainment and potentialities of the African stocks has recently come about, partly through the corrective influence of the more scientific study of African institutions and early cultural history, partly through growing appreciation of the skill and beauty and in many cases the historical priority of the African native crafts, and finally through the signal recognition which first in France and Germany, but now very generally, the astonishing art of the African sculptures has received. Into these fascinating new vistas, with limited horizons lifting in all directions, the mind of the Negro has leapt forward faster than the slow clearings of scholarship will yet safely permit. But there is no doubt that here is a field full of the most intriguing and inspiring possibilities. Already the Negro sees himself against a reclaimed background, in a perspective that will give pride and self-respect ample scope, and make history yield for him the same values that the treasured past of any people affords.

While studying abroad in Spain, I lived in the neighborhood along the Guadalquivir River called Triana, which was once home to one of the Black enclaves that Schomburg studied. My program was fairly progressive, repeatedly reminding us about the evils of the Inquisition and promoting the values of tolerance and equality…as well as checking the boxes of pro-LGBTQ and Muslim programming. I was appalled upon discovering that such Black communities existed, and of the aforementioned figures who lived there—which were never once mentioned in my classes. How could I have spent an entire semester in Spain (being taught about and visiting the works of Velasquez and Murillo) without having learned anything at all about de Pareja?

The exhibit highlighted for me how much of standard “woke” social justice discourse—and their anti-woke reactionary detractors—miss the mark. The actually stories of real people, real communities, in all of their complexity and nuance, too often get overshadowed by abstract moralizing and reductive discourse on power relations. It is too quick to ignore that which makes us human, and which makes society actually progress forward in concrete and meaningful ways.

The relationships between Caucasians and people of color surely was (and continues to be) characterized by unjust power imbalances—which includes matters pertaining to economics, legal rights, access to property, labor, education and healthcare. But there are also factors in this dynamic that are not measurable which complicate the narrative of race relations—factors like psychology, culture, art, faith…which was prominently featured in the presentation of de Pareja and Velasquez’s relationship in the exhibit (I explore this in my critique of cultural appropriation discourse aimed toward the Spanish singer Rosalia).

Further, social justice, when reduced to utilitarian matters of political and economic expediency (or worse, to regulation of speech), can give way only to short lived changes. “Man cannot live on bread alone.” Schomburg’s story accounts for the need for roots, beauty, tradition, spirituality, and communal bonds, in order to give people a sense of dignity and purpose…to provide them a reason to live.

My hope is that upon visiting the exhibit, proponents of wokeness and their conservative detractors will be provoked to broaden their scope toward matters pertaining to race. Further, I hope it will provoke people to, as Camille Paglia once said was a solution to the vapid and genteel moralism of the assimilated/WASP sensibility, “be ethnic!”—which is to say, to tap into their own ethnic roots, their own history, and to discover the artistic, spiritual, and communal legacy that their identity springs from.

For more on this topic, check out my essays on Rick Caruso and on Fr. Geno Baroni’s advocacy for multiethnic urban enclaves, as well as my podcast interviews with Albert Thompson, Justin Giboney, and Bill Melone.

$upport CracksInPomo by choosing a paid subscription of this page, or by offering a donation through Anchor. Check out my podcast on Anchor and YouTube and follow me on Instagram and Twitter.

photos taken at the Met.

Did Diego Ortiz de Zuniga have African ancestry?