After long await, here are some excerpts from my essay on Benedict, the postmodern Pope:

For me, Benedict’s affect, style of thinking, and overall aesthetic was emblematic of Catholicism’s unique cultural vision. With his esteem for the arts, his affinity for engaging with intellectuals whom most would deem far from the Church’s tradition, and his campy flare, he was perhaps—despite his measured critiques of it—the pontiff most in tune with and capable of speaking to the postmodern tides that Western culture waded into. Far from being a philistine, intellectually arid, or a bigot, Benedict—more than his predecessor and successor—is par excellence the pope of the postmodern era.

…

Written off later in his career by the mainstream media as “God’s Rottweiler,” Joseph Ratzinger was widely considered a progressive during the Second Vatican Council because of his openness to engage with postmodernism. His 1968 tome, Introduction to Christianity, straddled the paradoxical line between theological traditionalism and the contemporary, anti-foundationalist air of doubt and skepticism, allowing him to dig into the foundations of Christian belief.

…

Benedict shared with skeptics, postmodernists, and existentialists the suspicion of the modern trust in the benevolence of the human will. He was ready to admit that humans are messy and the natural world unpredictable. His willingness to grapple with the darkness of existence has more in common with thinkers like Marquis de Sade and Sigmund Freud, Nietzsche, and Albert Camus—as much as his conclusions may have greatly differed from theirs—than with the likes of Jean-Jacques Rousseau and John Locke.

…

As literary critic Wayne C. Booth once observed, “postmodernist theories of the social self have not explicitly acknowledged the religious implications of what they are about. But if you read them closely, you will see that more and more of them are talking about the human mystery in terms that resemble those of the subtlest traditional theologies.”

Benedict’s theological legacy foreshadowed the recent “horseshoe” phenomenon that occurs when divergent forms of religious traditionalism and contemporary counterculture (almost) intersect. The conversion of “Red Scare” podcast host Dasha Nekrasova comes to mind. According to recent pieces in the New York Times and Vox, Catholicism’s artistic, spiritual, and liturgical tradition is drawing in bohemian, artsy types who typically are considered alien to the Church. As mainstream culture continues to head in a stiflingly bourgeois direction—between its unimaginative aesthetics, puritanical political correctness, and repetitive political deadlocks—so-called hipsters are finding that they have more in common with the Roman Catholic Church than they do with conventional progressivism.

Perhaps the most overlooked and misunderstood of Benedict’s “horseshoes” is between his comments on sexual morality and his surprising resonance with queer culture. During his lifetime, Benedict received vehement backlash for his decisive stance on the moral implications of same sex sexual relations and his blocking of men with “deep-seated homosexual inclinations” from the priesthood. In his infamous 1986 “Halloween Letter,” Ratzinger insisted that sodomy is an “intrinsically disordered” act. “To choose someone of the same sex for one’s sexual activity,” he wrote, “is to annul the rich symbolism and meaning, not to mention the goals, of the Creator’s sexual design. Unable “to transmit life,” sodomy is “essentially self-indulgent.”

…

Figures such as Wilde would likely (and ironically) have felt more at home, not with Francis, but with the theology and cultural sensibility of Benedict, whose affect—like Wilde’s—has an undeniably “campy” flavor. Camp, according to Susan Sontag, “is not a natural mode of sensibility, if there be any such. Indeed the essence of Camp is its love of the unnatural: of artifice and exaggeration.” That is why gay men like Wilde—caught perpetually between the “extremes” of supernatural chastity and unnatural debauchery—have been known to be drawn to camp.

In an essay on camp, literature scholar Fabio Cleto comments on how Benedict was “totally démodé, so alien to popular experience and the limelight as to retire from the throne in impenetrable, Garbo-like indifference, thereafter graciously considering his successor’s efforts from a distance. So viciously elegant, so unrelentingly medieval.” Benedict’s papacy, he says, made for an “ultra-camp story.” What with his flare for the baroque, his appreciation for aesthetic beauty and the arts, his taste for extravagant liturgical vestments and pageantry, his reputation for reading people’s logical fallacies and being outspoken without much concern for social conventions, his keen awareness of the tension between the finite and infinite, the sacred and profane, the natural and artificial, one might dare to call Benedict the real “gay-friendly” pope.

With a knack for stirring the pot, Benedict had little concern for sentimentality, refusing to pander to or appease the public’s sense of complacency. Take his letter on the resurgence of the Church sexual abuse scandal in 2018, which, while demonstrating humble respect and obedience to his successor, obliquely criticized those who deemed simplistic bureaucratic solutions would be enough to clean up the Church’s messes. Similarly, his “politically incorrect” comments about the reality (as much as it may have been expressed in an imprudent manner) of Islam’s history of violence was stated so glibly, as if to follow his caustic speech with the phrase “just saying…”

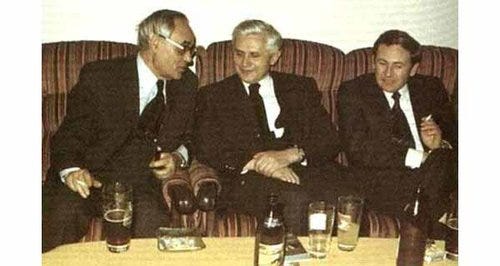

Benedict was the Christian equivalent of the Nietzschean Ubermensch. The antithesis to the bourgeois “last man,” he lived with gusto and a fervor for the finer things in life. He reveled in art, literature and music, and was a connoisseur of beer as well as indulging in the occasional Marlboro Red—unlike his party pooper-successor, who in 2017 banned the sale of tobacco in the Vatican as “the Holy See cannot contribute to an activity that clearly damages the health of people.”

Read the full essay at Hedgehog Review.

$upport CracksInPomo by choosing a paid subscription of this page, or by offering a donation through Anchor. Check out my podcast on Anchor and YouTube and follow me on Instagram and Twitter.