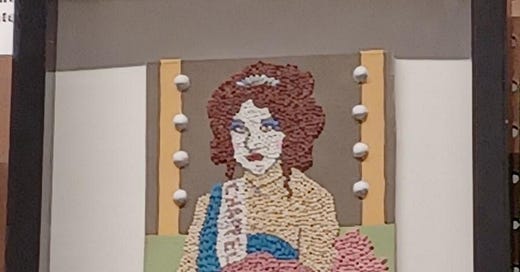

The Rise & Fall of a Midwest Princess: Chappell Roan – Crop Art by Jaren Yambing at the 2024 Minnesota State Fair

The cultural highlight of 2024 has been the ascent of Chappell Roan to stratospheric popularity, with her campy drag queen aesthetic, high-energy performances, and string of exuberant hits celebrating queer love and unselfconscious fun and hedonism from her album The Rise and Fall of a Midwest Princess and subsequent smash single Good Luck, Babe!

A friend who is in the demographic (a queerish Gen Z Catholic woman) suggested I give a listen, and so I listened to The Rise and Fall on repeat throughout much of the 1100 miles I drove each direction from where I live outside the Washington, DC suburbs to visit my family in Minnesota. What better way to drive home to the Midwest than by listening and singing along with a self-proclaimed Midwest Princess?

It's a phenomenal (Feminonomenal?) album: building on the strength of her vocal power and range, her emotional expression, and lyrics ranging from fun and playful (“Red Wine Supernova” and “After Midnight”) to heartfelt and lovelorn (“Kaleidoscope”) to vengeful and menacing (“My Kink is Karma”).

From anthems celebrating women finding sexual satisfaction with each other rather than with men (“Femininomenon” and “Super Graphic Ultra Modern Girl”) to a life of carefree clubbing “where boys and girls can all be queens every single day” away from the bewildered eyes of dismayed parents back home (“Pink Pony Club”) one might infer a rejection of home and a culture of colorless conformity, where instead it’s a consistent fulfillment of the “all-American” culture of the Midwest, more love letter than repudiation.

I could digress on how the republican ideals underlying the Northwest Ordinance of 1787 inform the region, but I’ll pass for now by saying simply that the Midwest (the region northwest of the Ohio River, but less clearly defined to the west and south) embodies an egalitarian spirit: polite, informal, industrious. However imperfectly we live it, Midwesterners have an optimistic spirit about the American dream.

The politeness, skepticism of socially complex rules, and informal bonhomie all combine as “Minnesota nice.” We have a simplicity and sincerity that others more jaded than us might call “cringe” or naivety. “If you can’t say something nice, don’t say anything at all” and “it’s impolite to talk about politics and religion at parties” are instructions we learn in school, for better or worse.

That Midwestern Nice has a darker side. The politeness can mask hatred and indifference, the silence can prevent speaking up against injustice for the sake of keeping peace, the skepticism of things perceived as fancy or arrogant can lead to a narrow-minded provincialism.

Against this darker side, we raise up talented satirists and individuals with great talent and colorful personalities and individual charisma that sets them apart from the conformity and social pressure to go along to get along. Satirists such as Sinclair Lewis (from Sauk Centre, Minnesota), Zucker-Abrahams-Zucker (the Airplane! filmmaking trio from suburban Milwaukee), the Coen Brothers (from the Minneapolis suburb of St. Louis Park), and the founders of The Onion (begun in Madison, Wisconsin) are among those that make us laugh at our foibles and shortcomings.

Charismatic performers and musicians such as Bob Dylan (from Hibbing, on northern Minnesota’s Iron Range), the entire Motown sound and Eminem from Detroit, to name just a few, have risen above polite conformity to iconic status, from which they call us to question our political, sexual, economic, and moral certainties.

Long before Donald Trump became a Camp King, former pro wrestler Jesse Ventura rode dissatisfaction with the political status quo to an improbable election as Minnesota governor in 1998 as a third-party candidate. He secured his place as political camp icon by wearing his trademark feather boa to his January 1999 inaugural ball.

Minneapolis’s native hero Prince combined galactic musical talent and vision with singular style and charisma in such a way that the overt sexuality of his music and the gender bending persona were just part of his being. “He’s kind of weird,” we might say, “but he’s a damn good musician, and he’s ours.”

The Midwestern intolerance of pretense makes it OK for you to be weird, queer, campy—provided you’ve got the talent and skill to back it up. In turn, there’s a mutual affection: We love the ones who put us on the cultural map, and they have a love for home.

Chappell Roan, from small-town Missouri, continues this legacy. Her raw talent and the obvious hard work she’s put into crafting musically and lyrically interesting songs, her campy, larger-than-life stage persona with no qualms about calling out VIP section fans who won’t cut loose and have fun dancing at her shows are part of this legacy.

The sexual liberation and hedonistic fun of her songs refer to the freedom found in the clubs of LA, but they’re tinged with a love and affection for home, for the sound of a mother’s voice in her head, for the seasons in Missouri (“California”). Even when we’re conflicted about it, about home and family, the love is always there.

And home loves back, too, as it can, whether it’s when the organist for the St. Louis Cardinals plays the native daughter’s hit “HOT TO GO!” during the seventh inning or when the Minnesota State Fair displays a portrait made of colorful seeds. We might be weird, but we love.

Colin O’Brien is a Minnesotan in exile in the Washington, DC area. He’s an Oblate of St. Benedict of St. Anselm’s Abbey in DC and writes at the recently-founded Substack “In Whose Blent Air.”