by Jonathan Mittiga

In A Grief Observed, C.S. Lewis reflects on the loss of his wife, Joy Davidman. Overwhelmed by grief, Lewis pours his emotions into a series of diary entries, a departure from his usual prose. "Her absence is like the sky, spread over everything.” Once a self-proclaimed bachelor, Lewis married Davidman at 58, only to lose her two years later. Was he too busy reading and teaching for a family, or did he simply prefer solitude? Hard to say—but his grief is visceral, described as akin to fear: “I am not afraid, but the sensation is like being afraid…. There is a sort of invisible blanket between the world and me. I find it hard to take in what anyone says. Or perhaps, hard to want to take it in. It is so uninteresting.”

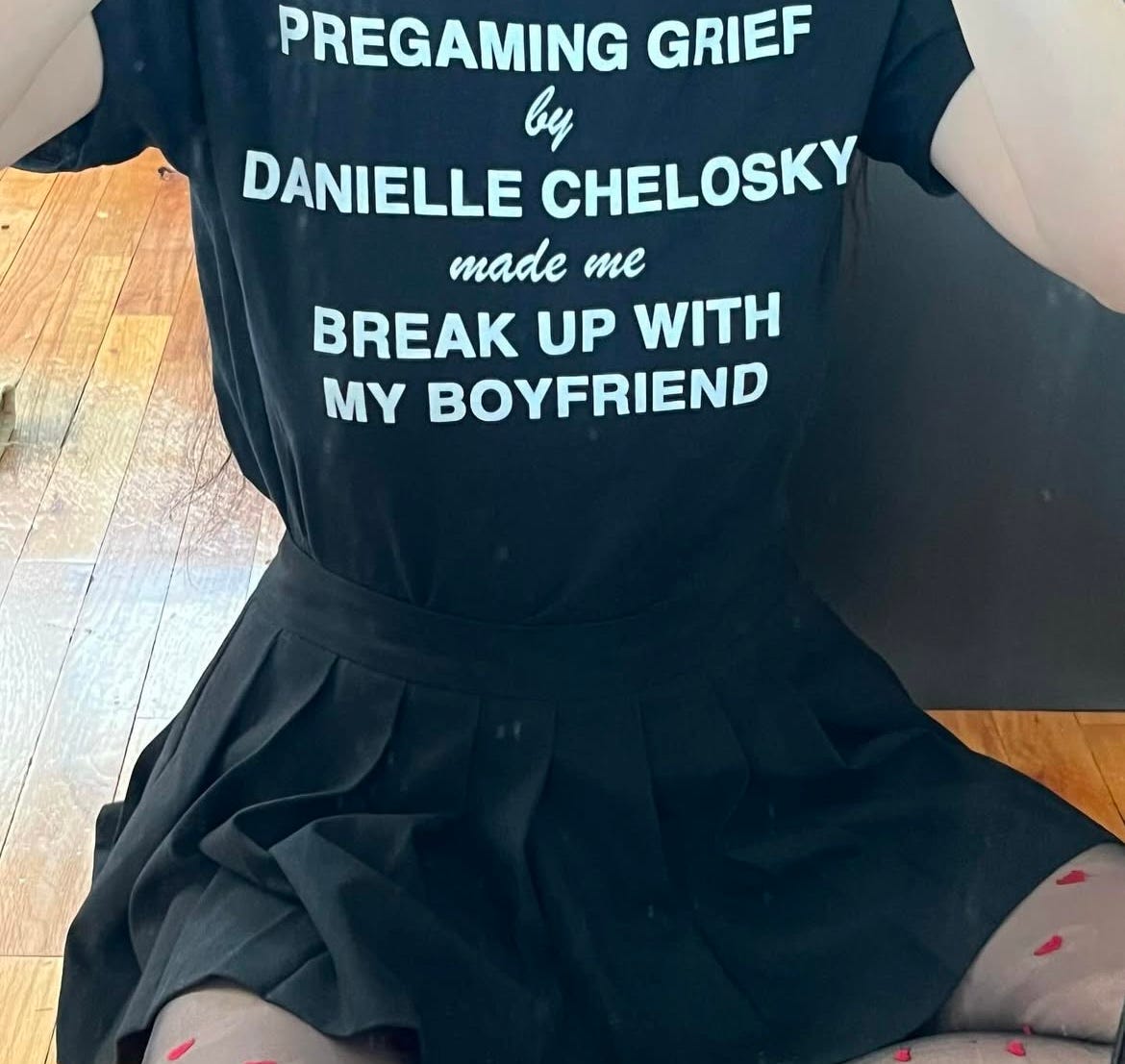

Pregaming Grief (2024) echoes a similar emotional cadence—structured as a diary but presented as a novel. Its nameless heroine is, transparently, the author: music journalist and Hobart editor Danielle Chelosky. The book recounts the summer of 2020, when Chelosky, a college intern living in Bushwick, becomes involved with two primary lovers: a 25-year-old heroin addict (to whom the book is addressed) and a thirty-something music journalist named Andrew.

Diaries of nymphomaniacal scenesters are trendy. Fans pose with Pregaming Grief on Instagram, calling it “their diary,” romanticizing its emo-style melancholy. But youth culture is a feedback loop, and Chelosky’s writing reflects the same influences that shaped her generation. She draws from the early 2010s wave of auto-fiction—decadent, self-destructive, self-referential—as well as from Annie Ernaux and Anais Nin. Naturally smart and clever, Chelosky is also young and impressionable. She recounts past events with a tone of reflection, yet continues engaging in the same behavior. Time needs to pass, and circumstances must change for introspection to yield true insight. A fast life does not mature into wisdom on its own—wisdom is weathered by time.

Chelosky’s prose is sparse, her storytelling direct. Her sentences do not show; they tell. When describing her infatuation with the heroin addict, her language meanders: “Being with you was some sort of cleansing, the kind that made me a good girl in a Catholic kind of way…I documented all my experiences with these men…like I was kneeling during confession and absolving myself of my sins.” There is an implicit spiritual yearning beneath her words—an inherited mustard seed of the Catholic faith. But for now, she is rocky soil.

Throughout the novel, she moves through a haze of parties, road trips, and hookups. She maintains “situationships” with her two primary lovers but also has sex with men she barely knows. One encounter is described starkly: “I dissociated, realizing I was finally in the moment I’d been waiting for all night, and it was nothing special, nothing even enjoyable.”

Her two main lovers are objectively bad men. The heroin addict goes to rehab and writes her sweet, scatterbrained messages like “I want to marry you, truly.” But she does not trust his amends, calling them a “weapon” he wields to re-enter her life. He is unreliable, and she is co-dependent.

He hits her—a kink she isn’t sure she enjoys: “Uninhibited by my intoxication, I told him to hit me....When his hand struck my face, it felt like waking up, or being resuscitated. I started crying...I was an emblem of shame. I was disgusted with myself.” Another time, he shoves her underwear into her mouth. “The degradation I felt was so antithetical to the feminist beliefs I held.”

As the book nears its end, her two lovers cycle in and out of her life. She begins matching with men on dating apps—out of boredom, or spite—not grief. She goes on dates, has sex with them, repeats. Nothing is learned. The loop continues. She convinces herself that Andrew loves her, “even if he is awful at it.” In the very next paragraph, she contradicts herself: “...I was unsure if what he provided me was really love.” At the novel’s conclusion, she resolves to reconcile with him. So much for empowerment.

Chelosky is not a bad writer, just lost. At times, she parrots feminist talking points from her women’s studies classes, grasping to cast her behavior as empowering. In that sense, she is not unlike Lily Phillips, a self-described feminist and OnlyFans star who made headlines in December when she produced a documentary of her experience allegedly sleeping with 100 men in one day. But like Phillips, Chelosky’s actions tell a different story, one of disillusionment and brokenness. She is not pregaming grief so much as pregaming nihilism. One day, she may grieve the dignity she forsook at an SLAA meeting.

Bridget Phetasy, writer at Beyond Parody, once reflected on her own hookup years: “At the time, I would have said one-night stands made me feel ‘emboldened.’ But in reality, I was using sex like a drug; trying unsuccessfully to fill a hole inside me with men. (Pun intended.)” She continues, “Let me be clear, being a ‘slut’ and sleeping with a lot of men is not the only behavior I regret. Even more damaging was what I told myself in order to justify the fact that I was disposable to these men: I told myself I didn’t care.”

Another mature writer, Louise Perry, writes in The Case Against the Sexual Revolution,: “The new sexual culture isn’t so much about the liberation of women, as so many feminists would have us believe, but the adaptation of women to the expectations of a familiar character: Don Juan, Casanova, or, more recently, Hugh Hefner.” Chelosky is charismatic and friendly, but she is caught in a cycle of proving her worth to men through sex. She forms emotional attachments to bad men, too caught up in the moment to consider her future marriage—if she ever considers marriage at all.

It goes both ways. Perry argues elsewhere, “When men must be marriageable in order to access sex legitimately, they will do everything in their power to transform themselves into marriageable men.” But in a culture where marriage is no longer obvious, or necessary, some women resist it as patriarchal.

C.S. Lewis, it is rumored, never consummated his marriage with Davidman. His love for her did not manifest in physical desire, which might have seemed queer, even in the pre-sexual revolution 1960s. But it was a mysterious and deep love nonetheless. Chelosky, by contrast, is a product of the post-sexual revolution. Freely giving herself away to numerous men, she might struggle to comprehend what made Lewis so spiritual.

Chelosky is still searching. Her actions may be a forgivable rite of passage for a scenester in Bushwick, but they will not satisfy her long term. She is not soulless—just empty—and her novel reflects this. But emptiness can be filled, and that might make for a better story.

One day, she may yet be surprised by the joy of love. Hopefully, she’ll document that experience with the same care she poured into Pregaming Grief.

Note: This review falsely indicated that one of the characters’ names in the novel was the real name of an actual person in the author’s life. We removed the error.