if you’re interested in preordering a copy of cracks in pomo: the zine or in making a financial contribution, email stephenadubato at gmail dot com

“More and more frequently, and it pains me to admit it, I felt a desire to be liked. On each occasion a little thought convinced me of the absurdity of this dream; life is limited and forgiveness impossible. But thought was powerless and the desire persisted–and, I have to admit, persists to this day.” -Michel Houellebecq in a letter to Bernard-Henri Lévy

I’m getting tired of these trads—both the ironic and unironic ones—decentering Jesus from Christianity. The whole point of Christianity—as Pope Francis has reiterated over and over again—is to be happy. Not to be right, not to be good, not to be based, but to be full of joy. While the moral and political implications of Christianity are deeply important, they are secondary to…flow out of, the relationship with the person of Jesus. To reverse the order is to render Christianity and ideology…which will make no one happy.

Thank God Houellebecq has figured this out.

On Good Friday of 2023, my understanding of the relationship between Houellebecq’s works and the Easter Triduum was made more profound, more personal. After walking in a Way of the Cross procession from Brooklyn into lower Manhattan, I made my way uptown to a Tridentine Passion service in Midtown. I got distracted en route by a “subversive” bookstore filled with young people decked with nose rings, purple hair and gender-nondescript clothing. I quickly put out my Lucky Strike, rubbing it into a fire hydrant until I had annihilated the last orange spark (tobacco is the one indulgence I allow myself whilst fasting). As I walked in, I hesitantly asked the sales clerk, who was aimlessly scrolling through Instagram whilst manning the register, to help me find a book.

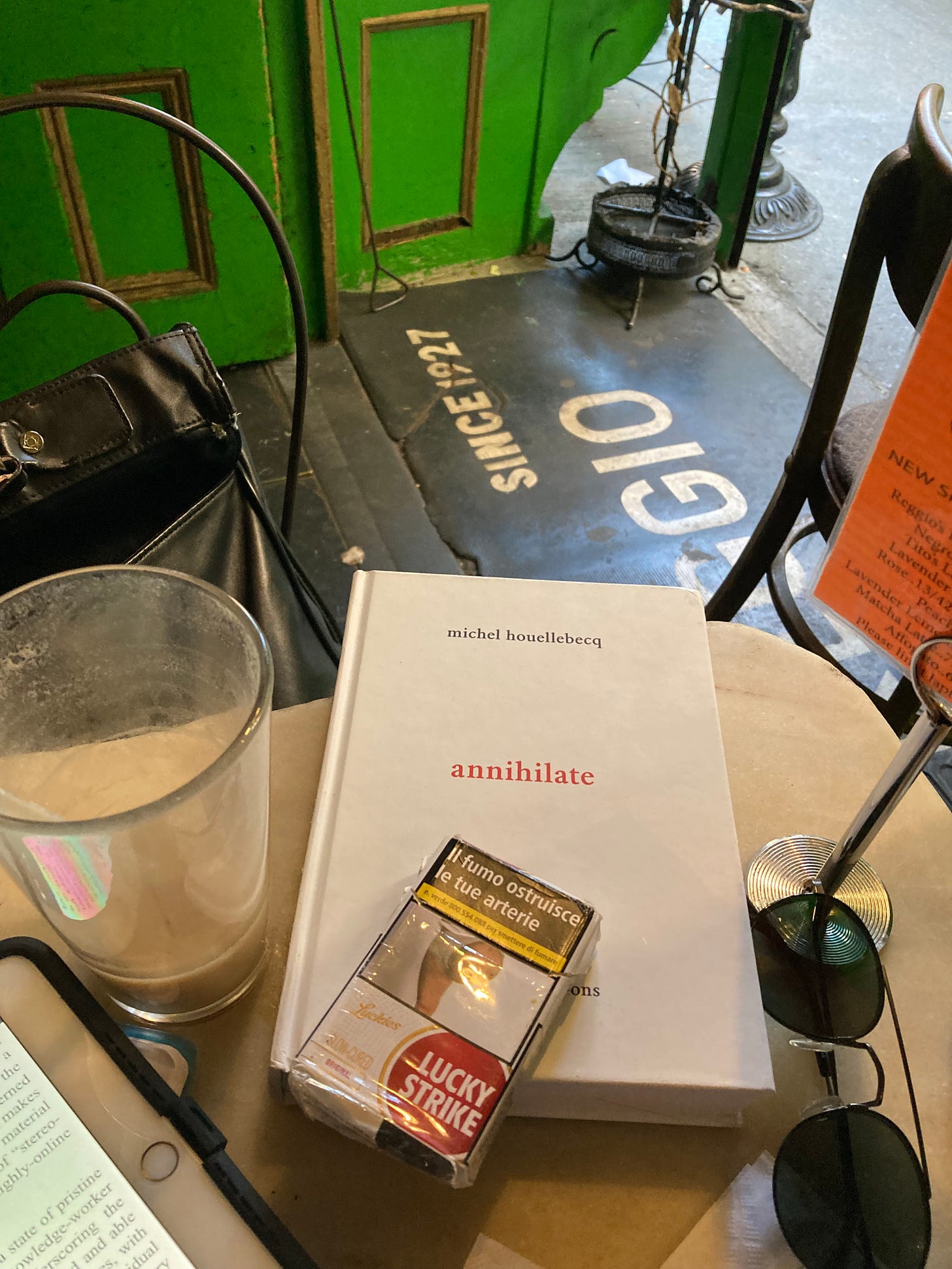

“Sorry, we don’t have a computer database” — how countercultural, shocker — “but you can look in the fiction section.” I should have known better than to presume to interrupt his scrolling session. As I began searching, I happened upon a thick, square-shaped book with Houellebeq’s name written along the top in all lowercase characters. It was lying on the “Featured Books” table, with annihilate traced in a blood-red tone across the middle.

“Damn, this is out already?” I exclaimed to the clerk, baffled by the fact that I was not aware that the long awaited novel had already been released. “I didn’t hear anything about it online yet.”

“Yeah,” he muttered without looking up from his screen. “We just got that one copy in yesterday.”

On my way home from the church service, I started searching the web ravenously for information about the book’s official release date. The English translation was unavailable on all major book vendors’ websites, and no news about it was to be found anywhere. Weird …

As I spent Holy Saturday devouring the novel, it quickly became clear to me that there was no way that this copy could be an official translation. Littered with literal translations, it read like it was put through Google Translate. Could it be, I wondered, that the apathetic clerk accidentally put a galley copy of the book out for sale? I never thought I would say this, but thank God for millennial laziness.

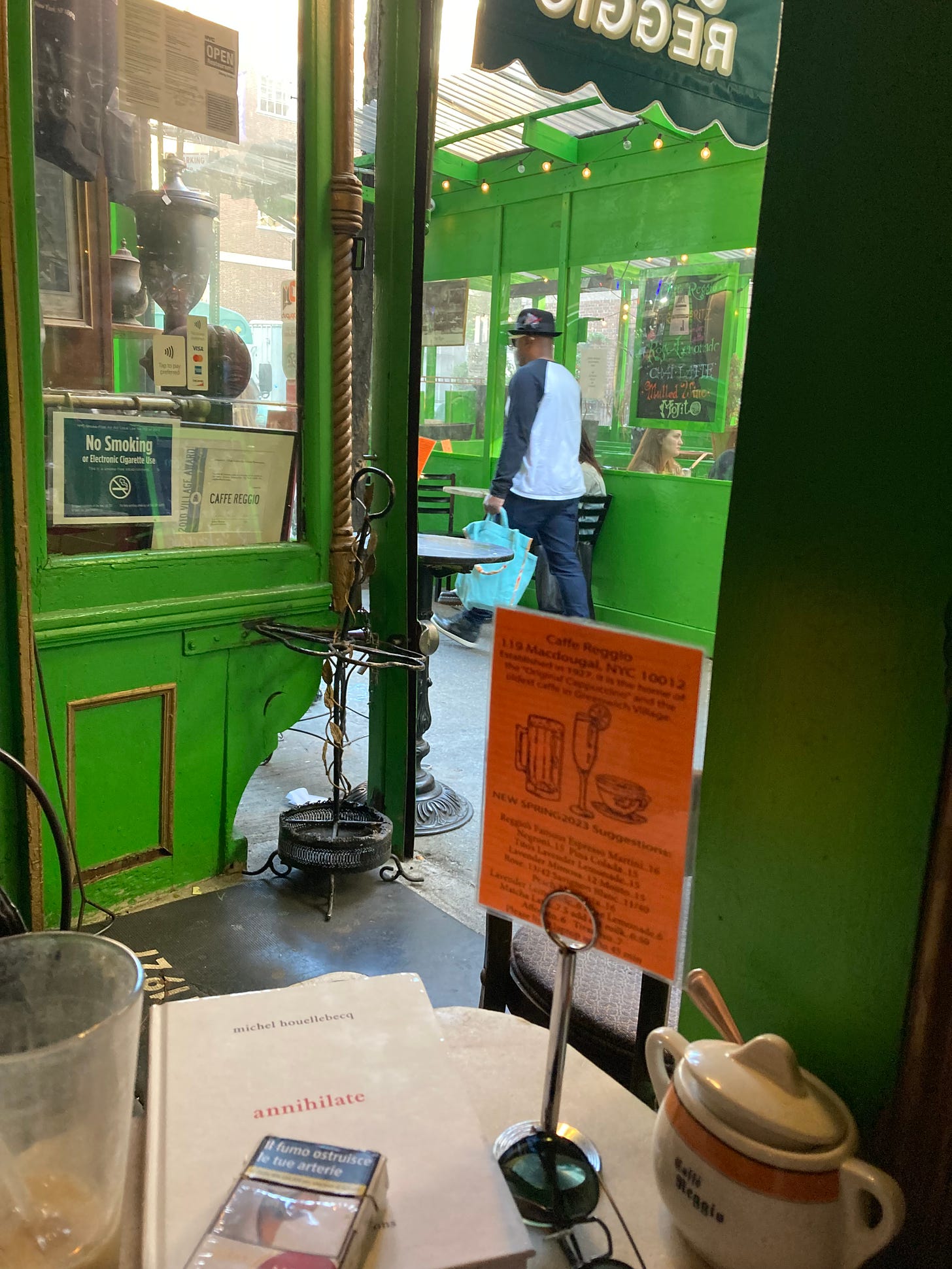

On Easter Sunday, I gave praise to God — becoming the first person in the anglophone world to read Aneantir was evidently his reward to me for “submitting” to his will on Good Friday by following the cross, the instrument of his “annihilation”, over the Bridge. I carried the book with me throughout Easter week, ostentatiously displaying it on the table where I was sitting at a coffee shop and posting pictures of myself reading the book on Instagram … much to the envy of my followers — some of whom offered to buy it off me. But no. This was my reward from the Almighty, who had smiled widely upon me and showered me with this gift.

Perhaps the novel’s greatest surprise is its implicit esteem for Christianity. This time, his treatment of Christianity is not merely ideological — which is to say, reduced to its secondary, political or moral implications — as it usually is in his others. In Annihilate, Christianity is presented in a much more personal and simple manner: the Christian characters’ faith in the God who “so loved the world that he sent his only son” are the only ones who appear to be genuinely happy and free in the midst of suffering. For the first time, Houellebecq seems to be getting at what is essential, what is most primary to the Christian faith: the person of Christ himself.

Raison finds himself struggling (as his surname alludes to) but desiring to believe in the god his sister, Cecile, worships. What attracts him to her faith is not its ties to moral order or “Western Civilization”. On the contrary, his sister has little interest in the “traditional Catholic fundamentalists” who are involved in political conflicts that arise throughout the novel. Those Catholics seem to have lost sight of the fact that the Incarnation, Passion and Resurrection of Jesus are impetuses not to engage in ideological battles, but to “rejoice and be glad”.

Whilst visiting their ailing father in the hospital, Paul feels a sudden urge to “grill a cigarette” (good job, Google Translate). “If there is a place that produces stressing situations, if there is a place where the need for tobacco quickly becomes intolerable, it is a hospital.” When facing the possible death of a loved one, what could satisfy one more than a cigarette, he asks. “Jesus Christ, Cecile would probably have answered. Yes, Jesus Christ, probably,” he admits (and I couldn’t agree more, especially when lighting up a bogey after having walked three miles in the cold to pay public witness to Jesus’ death on Good Friday).

Cecile’s joy, her sense of peace and hope in the face of suffering, and her willingness to be a loving presence in the midst of their family crises, all captivate her brother. Paul is inspired to start frequenting a nearby church — not exactly to pray in a formal sense — but to offer his desire to have a special “connection” with God, to be on a first name basis with God, as does Cecile.

It’s no secret that a slew of “trad Catholics” — from Dimes Square scenesters to integralists — are fans of Houellebecq. His derisive, satirical attitude toward Western secular neoliberalism overlaps with their ideological commitments. I won’t be surprised if said trads find themselves bored or disappointed with Aneantir, however, for taking its cues more from Pope Francis’ “joy of the gospel”-type rhetoric than from Cardinal Sarah’s “funeral march of the West” rhetoric (though I’ll be the first to point out the convergences between the two).

As much as my trad sympathies are no secret to those who know me, I must admit feeling refreshed and even inspired by Houellbecq’s shift in tone. Faith in Christ does indeed invite us to a measured engagement in social and political affairs, but I find that too many of my contemporaries allow their ideological agendas to cloud their familiarity with the person of Jesus and the joy born from that encounter with him. By itself, a Christian “moral revolution” will likely prove incapable of making people happy in the midst of their humdrum daily affairs and the pangs of suffering. At the end of the day, isn’t that what matters most — what has the capacity to attract people in the way that Christ himself did 2,000 years ago?

Read the rest at The Critic UK.

$upport CracksInPomo by choosing a paid subscription of this page, or by offering a donation through Anchor. Check out my podcast on Anchor and YouTube and follow me on Instagram and Twitter.

photos taken in the West Village.

This is very intriguing. I will wait (patiently, I hope) for the official English translation to come out.

You made me buy it in French