Before reading this piece on the NYC pride parade, check out my piece in Compact on ACT UP’s Stop the Church riot, in First Things on how everyone is gay now, and my appearance on the Compact podcast on the anniversary of Obergefell.

While visiting a friend in Washington, DC, last month, I was perplexed by the sheer number of premature rainbow flags, logos, and crosswalks adorning the city. “It’s not even June yet,” I scoffed to my friend. “Besides, these people clearly missed the memo that Pride is out.” That last bit is in reference to the fact that many gay people I know in New York City no longer attend Pride events. Indeed, the only people I know attending the parade in NYC today are straight girls.

When visiting DC, I’ve had to get used to checking my New Yorker privilege at the door; Gotham always seems to be ahead of the curve. It will only be a matter of time until the DC gay community catch on to what their brethren in the Big Apple have long ago realized: that with the legalization of gay marriage, the subsequent domestication of gay sex, and the mainstreaming of gay lingo, Pride didn’t feel it belonged to gay people anymore. If your Pride march was sponsored by J.P Morgan, was it any fun?

More recently, a new and even stranger twist has unfolded. To wit, this year, there was a mass exodus of corporate sponsors afraid of upsetting the Trump administration by supporting LGBT rights. Millions of charitable dollars have been pulled from these events. The flight of so-called rainbow capitalism highlighted true culprits behind Pride’s ruin: straight girls who’ve turned the event into a boozy brunch opportunity in the name of “allyship.”

“Allies have taken over Pride,”

, a Brooklyn-based writer and photographer, told me. As a result, gay men flock to spaces that “have nothing to do with Pride as a celebration.” But what happens,” he continued, is that straight girls “like to post content and messaging” that signals their “surface-level allyship” without understanding the nature of gay culture and “emptying it of its subversiveness,” which comes off as “so annoying and base.”It has become something of a mark of status for professional-class straight girls to acquire a gay bestie or two, just as she might a trendy accessory or article of clothing. Yet the heat of Nietzschean réssentiment and Freudian tension boils under the surface of the relationship between a gay man and his fawning friend.

At first, the dynamic between a “hag” and her “GBF” (gay best friend) is transactional. He tells her she looks fabulous in that dress, and in return, she encourages him to “slay,” “go off,” and “sashay away, queen.” On top of this, he affords her easy morality points—making her feel good for being on the “right side of history” without even having to lift a finger. He provides her all the benefits of male attention without the fear of rejection or the menace of aggression, and she offers him a quasi-maternal affirmation. She becomes, in short, what Lady Gaga has become to her devotees: a Mother Monster, feeding off of her “child” and thereby infantilizing and emasculating him.

I’ve known many gay men who, after a while, begin to resent their straight-girl friends for keeping them stuck in the womb, so to speak. There’s a yearning to break out and assert his manhood, to live as a gay man — with all the risks and thrills that come along with it. At a certain point, some gay men will forgo the straight bestie — and likewise the rainbow-flag-toting nanny state that assures him that his lifestyle is tame and bourgeois, threatening ostracism for anyone who thinks otherwise.

The inverse of the straight female ally is the “gay icon”: an archetypally powerful, goddess-like woman. She is an object of worship—embodying an eternal ideal that transcends the mundane and earthly—unlike the bestie who is reluctantly put up with. The extensive history of diva-fandoms demonstrates this difference.

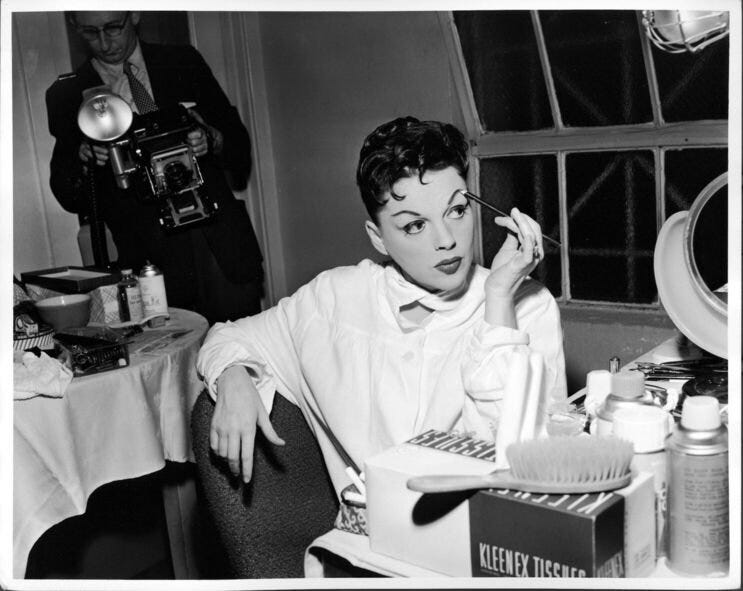

Perhaps the earliest and most iconic example is Judy Garland, whose glamorous yet tragic life and death fascinated gay men. Her funeral in New York City on June 17, 1979 (the same day as the Stonewall Riots) drew her devotees in droves, becoming a pilgrimage of sorts for many gay men. Garland, who played Dorothy in The Wizard of Oz, inspired the code “friend of Dorothy,” which is used to indicate someone is gay. And some believe that her rendition of “Over the Rainbow”—whose message of hope after having overcome a struggle spoke to persecuted gays—gave way to the gay rights movement’s use of rainbow flags.

Such deific divas include others actresses like Liza Minelli and Barbara Streisand, singers like Cher, Madonna, Beyonce, Lana Del Ray, and Kylie Minogue, comediennes like Joan Rivers, media personalities and public intellectuals like Wendy Williams, Camille Paglia, and even the conservative commentator Ann Coulter, who has been called “the right-wing Judy Garland.”

There are conflicting theories as to what incites gay men to worship these kinds of women. Aside from the fact that most of them have vocally supported the cause of gay rights, these women usually have endured and overcome some kind of hardship or tragedy. The “tragic figure theory” has been advanced as early as 1969 by writers like William Goldman, who wrote in Esquire that “homosexuals…are a persecuted group and they understand suffering.” Who goes on to cite Garland, who has “been through the fire and lived—all the drinking and divorcing, all the pills and all the men, all the poundage come and gone—brothers and sisters, she knows.” Patti Lupone, the Broadway diva, made this clear in her recent viral New Yorker profile, when she said: “Why am I a gay icon? … I think they see a struggle in me, or how I’ve overcome a struggle. What else am I going to do?”

When LuPone recently threw shade at black Broadway stars Audra MacDonald and Kecia Lewis, it was mostly straight girls who condemned her “micragressions” as “racist.” Such insipid reactions demonstrate their inability to appreciate—let alone comprehend LuPone’s characteristically “cutting remarks and “refreshing candor,” which appeal so much to her gay fans.

When asked why she is considered a gay icon, Kylie Minogue said that “it’s always difficult for me to give the definitive answer because I don't have it.” Despite having had “a lot of tragic hairdos and outfits,” she admits that she hasn’t had a very tragic life story. “My gay audience has been with me from the beginning…they kind of adopted me.” Many gay men flock to the glamorous, larger-than-life personas of performers like Minogue, whose beauty and gravitas reaches cosmic proportions. Others are admired for their fierce attitudes, unafraid as they are of breaking taboos, and rarely if ever backing down from a fight or conflict.

The dynamic between the gay devotee and his iconic diva is markedly distinct from that of the cloying ally and her Gay Best Friend. She desperately wants him to feed off of her, and feels entitled to appropriate gay culture and lingo without fully understanding any of it, whereas gay icons and their fans have a more mature, reciprocal relationship. They respect each other as adults, and mutually inspire each other.

Unlike monstrous mommies like Gaga, “mothas” drag their gay male devotee out of the womb and tense his being toward the prospect of greatness, forcing him to become a man. She will not console him, telling him that he’s fine as he is since he was “born this way.” She’s not one to coddle—she’s a mother who will whip him into shape, inspiring him to risk his life for ideals as lowly as hedonism or as high as artistic creation. She wants him to endure the struggle and emerge from it stronger, tougher, and more fabulous—just as she has.

While she advocates for gay rights, the diva has no interest in pandering to her gay fans, nor in enabling their victim complex. Furthermore, the icon has no need for her disciple: She does not depend on them as the hag does on her GBF, which is precisely what makes her so alluring.

And so, ten years on from Obergefell, it should be no surprise that numerous gays in New York City are leaving behind pride celebrations—and their straight girl besties—to pursue greener, more thrilling pastures. If there’s any hope for queer culture to flourish again — to become exciting and subversive—the rest of the world must follow the cues of these gay New Yorkers by exiling the straight-girl ally for good.

In the words of Cher, “If grass can grow through cement, love can find you at every time in your life.” It was the goddess-like divas like Cher who smoked through the suffering, belted through the drama, and turned pain into pageantry. Let us pray for such a resurrection of a true diva out of the ashes—not one that will post a rainbow-flag Canva post on Instagram, but who could turn water into vodka sodas and homophobia into dust with a single raised brow.

As an avoider of crowds I have seen this from a distance, having to come up with excuses to a broader swath of the public every year, and am glad to know I was not seeing things.

Years ago there was a Dan Savage caller who was, for lack a better term, a jilted fag hag. He talked about how many women get a lot of emotional support from gay men, particularly in high school before he has fully come out. So when the man fully embraces his identity and starts spending less time with her, it's like having her best friend break up with her. Dan used it as a chance to remind gay men to treat these women with compassion.