Originally Published in Convivium Journal, available for purchase at Amazon

My grandfather grasped the chant stand with both hands, the rest of his body vibrating along with the timbre of his voice. His soaring notes and roller coaster-like melismas painted a luscious, colorful backdrop against the stage set before me. It was Good Friday, the day in the Orthodox liturgical calendar I've always awaited anxiously, because of its sacredness and theatricality.

As the priest bolted down the main aisle flinging droplets of rose water out of gilded bottles onto the people, who then prostrated themselves and vigorously made the sign of the cross three times, an acolyte began swinging a censer back and forth. Behind him, seven young girls processed around the wooden tomb, their white dresses ruffling against the beams supporting the structure as they strewed red rose petals onto the floor, while mourning the death of their Bridegroom.

“O my sweetest springtime, O my sweetest Child, where has your beauty vanished?” The byzantine Good Friday lamentation hymns consist of vivid poetic verses; some come from Psalm 118 (chanted during Orthodox funerals), and others are a creatively imagined dialogue between the Sorrowful Mother and Jesus as he awaits his resurrection from Hades.

Though I barely understood liturgical Greek when I was six years old, I was fluent in the language of beauty, which allowed me to be allured by my grandfather’s chanting. Each year, the anticipation built up to these haunting sights and sounds, which penetrated my being and opened a flood of expectation, fear, and longing. Unable to put my feelings into words, I was enveloped by this mystery. My longing felt like a kind of offering itself—the only response I could give.

Easter came, and then the festivities would die down as I went back to the humdrum routine of life as usual. The surmounting stress at the end of the school year and tense family relations seemed disconnected from the sensations I felt on Good Friday. It was as if I had reached the peak of a mountain range, only to be cast down into the valley, where life was dull and predictable. All I could do was wait for next year, for that train to come and carry me up to the peak once more.

When I was a child, it was easier for my eyes to brim with wonder. But as my elementary years progressed, I dwelled in the valley, lower and lower, and it was harder to feel wonder. In high school, the desire to be liked, and to know that my life was affirmed by someone who was not me, intensified and collided with my erotic longings and my need to possess beauty, to find a “you” that would belong to me, exclusively.

Toward the end of high school, social expectations became all the louder and more dissonant: Get good grades. Get into college. Get a good job. Live a nice comfortable life. And then... die? My need, my cry for meaning, started to drown out the voices that demanded complacency and conventionality. I intuited that the common way lacked profound value in itself. So why was I wasting my time chasing ideals for which no adequate reasons were offered?

This question and my desires became more urgent as the ever-building tension between my parents and me reached breaking point. My parents’ divorce had inflicted a wound on me that, even after fourteen years, had not healed, and I was suspended in a web of anxiety, pain, and uncertainty, desperate to be cut loose.

I needed resolution. I needed peace like a beautiful fountain welling up. I felt myself trapped in my longing for something that seemed inaccessible, yet ever so necessary. But what could possibly answer or resolve this difficult, unnamable tension?

Now, I had grown up listening to soul music and Motown, and that music started to sound differently in my ears. I recognized in those powerful, emotive voices—of Whitney Houston, of Luther Vandross, of Sade and Mariah Carey, of Disco Queen Donna Summers—the yearning in my own heart, and I began to cling to this music for dear life.

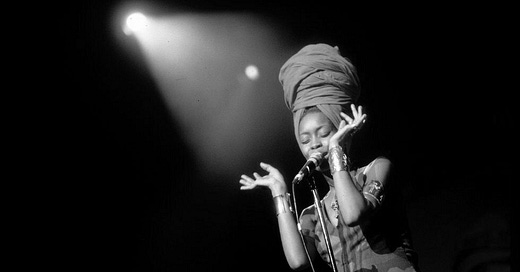

One Thursday afternoon in my high school senior year, I was watching VH1 and was bowled over by an eccentric head-wrapped songstress with rich and earthy vocals, cryptic lyrics, and lush instrumentation. I lay on the floor listening to Erykah Badu’s song as it enveloped me in a drama so human, so familiar. What could have given way to this kind of profound beauty, attractive and yet far off and intangible? I couldn’t hold on to the music, but I wanted to.

I had always been drawn to R&B music and to the catchy beats and vocal stylings of Chris Brown, Beyonce, Usher, and Aaliyah, but there was something distinct about the singers of the so-called neo-soul movement with their combination of live instrumentation, hip hop production, and socially conscious lyrics. Discovering them confirmed my heart’s intuition that the answer it was longing for was not the stuff of delusional fantasy, but that it existed in the flesh.

The wah wahs of the electric guitars and entrancing percussion on Maxwell’s Urban Hangue Suite and D’Angelo’s smoke-like crooning made me want to drift off into this mysterious realm where resolution to my ceaseless inner tension seemed possible. As I delved deeper into the various forms of soul music during my senior year, examining my favorite songs from beginning to end, reading stories about the artists and their influences, I started to recognize a common thread. Contemporary soul music echoes its early origins: the spirituals sung by slaves.

I had learned in history class how contemporary soul music had its roots in jazz, the blues, and gospel music, all of which emerged from the black American experience. Slave spirituals depicting tumult, beauty, and perseverance in the midst of suffering had given rise to the kind of longing that resonated with me first in R&B and soul music and later in neo-soul.

Now, I had to acknowledge that those roots were foreign to my experience in so many ways. For one, my roots trace back to Italy and Greece. My ancestors came to America freely, and were not forced against their will and enslaved. And yet, despite the vast difference between me and those people whose music shaped the sounds I listen to today, there is something I share in common with them. Their suffering speaks to something universal in the human experience. The desire for liberation in the midst of suffering, the longing for peace in the midst of conflict, speaks to me. And though contemporary soul music may not be explicitly about that yearning to escape an unbearable trial, it does indeed speak to the yearning for freedom and for happiness that no earthly comfort or earthly peace can resolve. I too needed resolution. I too needed a reason. I was tired of inexplicable tension, and this music gave me hope in the midst of my seemingly endless travails.

As senior year came to a close and the time to move on to college approached, the tension with my parents was further inflamed. I was stuck deciding between two schools, and the financial details led to numerous disagreements. In crisis, I urged my father to bring in a third party—his therapist—to attempt to insert some objectivity into our back and forth. My father reminded me again and again how much he loved me and demonstrated that through all the sacrifices he made for me throughout my life.

“That may be true, Steve. But at what point are you going to just listen to your son is trying to say?” This question marked a turning point in my relationship with my father, and he started going out of his way to listen before reacting. With this, my own healing began: I could rest in the comfort of knowing I could rely on my father’s earnest efforts to grow in patience.

There was a newfound sense of peace as I began college, and I found myself faced with an exhilarating sense of freedom. I enjoyed roaming the streets of Manhattan, exploring life in the dorms, and discovering things about the world in my classes. But, oddly enough, I felt like there were craters within my heart, and that sense of hope I’d found in music seemed irrelevant. The mellow vibe in the music had little to do with the radical tremors of freedom I felt.

I was sharply aware of just how deep my desires for happiness, beauty, and truth really were. The things upon which I rested my certainty in life were becoming more and more bland and unexciting. I wanted more. And no amount of comfort, serenity, or success quelled that longing. I couldn’t settle for “potential” answers. I couldn’t wait for an answer that would reveal itself “soon enough.” I needed to know now what this longing was and what could answer it.

My hope was urgent, and it was for something within the horizon of my freedom—for a sound to help me explore that feeling of suspension with which I was familiar. I was reaching higher and higher for an unattainable ideal, and very quickly, my musical tastes started to change.

Perhaps it was the mixtape of random songs the girl next door burned for me toward the middle of my freshman year. I recognized rhythms that I hadn’t heard since I was at middle school dances. That pounding repercussion I knew as reggaeton awoke something in me that perhaps was dormant back when I first heard Daddy Yankee’s single “Gasolina” when I was thirteen years old. It was similar to hip hop, yet tinged with more of an island flavor. The combination of snares, kickdrums, and timbales were more akin to the reggae/dancehall sounds of Jamaica. The underlying trecillo rhythm also found its roots in the music brought to the Americas during the slave trade.

I found in this electrifying combination a companion to, or even an echo to, the drama that was building up in my heart. The bounce and intensity of the beat, the daring delivery of the lyrics, reflected the intensity and daring of my whole body.

There was something extreme about reggaeton. It was the beat, the brazen disregard for propriety in the lyrics, the recklessness of a libido released without inhibition. As I listened, danced, and sang the songs of Wisin y Yandel, Don Omar, and Zion y Lennox, my demand for an answer intensified, but made the anticipation for its coming all the more exhilarating.

On weekends I went to nightclubs to feel the power of this sound at full throttle. In this setting, speakers throbbed and captivated people danced, and I was at the apex from which I never wanted to be cast down. But because of the sweetness of these heights, in the back of my mind was fear that the ephemeral moment would end; I looked around for someone, anyone, to promise me that it would never end. And at the end of the evening, I would find myself down in the valley, awaiting the next time I could achieve those heights again.

Somewhere in climbing and descending this proverbial mountain, I encountered something that caught me in my tracks. I had made several new friends during my freshman year, and there was something different about the friends I met through one classmate of mine. Something about the way they talked, the way they treated each other and looked at life—at their work, at their relationships, at life’s highs and lows—offered me a view of eternity. When I was with these people, I became aware that the “answer” I was looking for was undeniably available and present within our midst.

Interestingly enough, these friendships helped me perceive that this mysterious answer was the One sung in the byzantine chant of my childhood. This is when I encountered, as a living presence in my group of friends, this man for whom the girls had scattered petals in mourning and whose name my grandfather sang repeatedly. In these friends, who looked at life joyfully and who treated me tenderly, I recognized that sense of sacredness during all those past Good Fridays. Only this time, that alluring mystery, that sacred beauty, had made itself flesh in the faces of these friends.

This encounter through friendship renewed and expanded my appreciation of all the music I love. No longer desperately grasping or anxiously trying to possess what I hear, I find myself listening with an overwhelming sense of gratitude. Now I know that this beauty points to something beyond itself which fulfills the longing within me. This presence has not brought an end to what the music stirs up in me, but rather carries me to heights that surpass mountain peaks.

As years go by, I’ve entered more deeply into my friendships with these exceptional friends, discovering that what I share with them has not replaced the significance of music in my life. It hasn’t rid me of the desire to scrutinize details of the beat or to dance at a club with the volume at full blast. Longing is part of this experience when I’m out dancing, and I’m still faced with the awareness that the thrill of the moment will end. Still I look for Someone to bring me the promise of eternity. Only now, I’ve seen the promise—my answer—in the faces of my friends.

Check out my podcast episodes about the philosophy of R&B, reggaeton, Brasilian funk, and my articles on the spiritual charge of pop music, old school reggaeton, newer reggaeton, Brasilian funk, Mariah Carey, Romeo Santos, Bad Bunny, Lauryn Hill, and Amy Winehouse.

$upport CracksInPomo by choosing a paid subscription of this page, or by offering a donation through Anchor. Check out my podcast on Anchor and YouTube and follow me on Instagram and Twitter.