It is of course true that the sort of vampires featured in the Twilight series are quite a bit different from the vamps of, say, the Anne Rice novels, or even the fantastically Nineties ones from Buffy. The Cullens and co. have skin like granite and sparkle, rather than die, in the sun. That they deviate so much from what the word vampire tends to bring to mind is mentioned frequently in the stories, as though their creator were insecure about it, which she bloody well ought to be. Twilight seems like an exercise in taming vampires to facilitate the romantic fantasising of teenagers. And tame vampires are crashing bores.

But most of the iconic vampires—Bela Lugosi’s Dracula, say, or even Sesame Street’s Count von Count—are deviations from the O.G., a mythical creature from Eastern Europe described as bloated, ruddy, shrouded, and fangless. It wasn’t till John Polidori wrote ‘The Vampyre’ in 1819 (incidentally, as part of the same literary contest out of which Frankenstein grew) that we came to see this creature as gaunt, pale, privileged, articulate, seductive, corruptive, and hot. So the vampire villain of Robert Eggers’s Nosferatu, a hulking beast of a thing, is a return, rather than a departure; and if that disappoints viewers weaned on Buffy’s Spike or the Dracula of Christopher Lee, it won’t be for long.

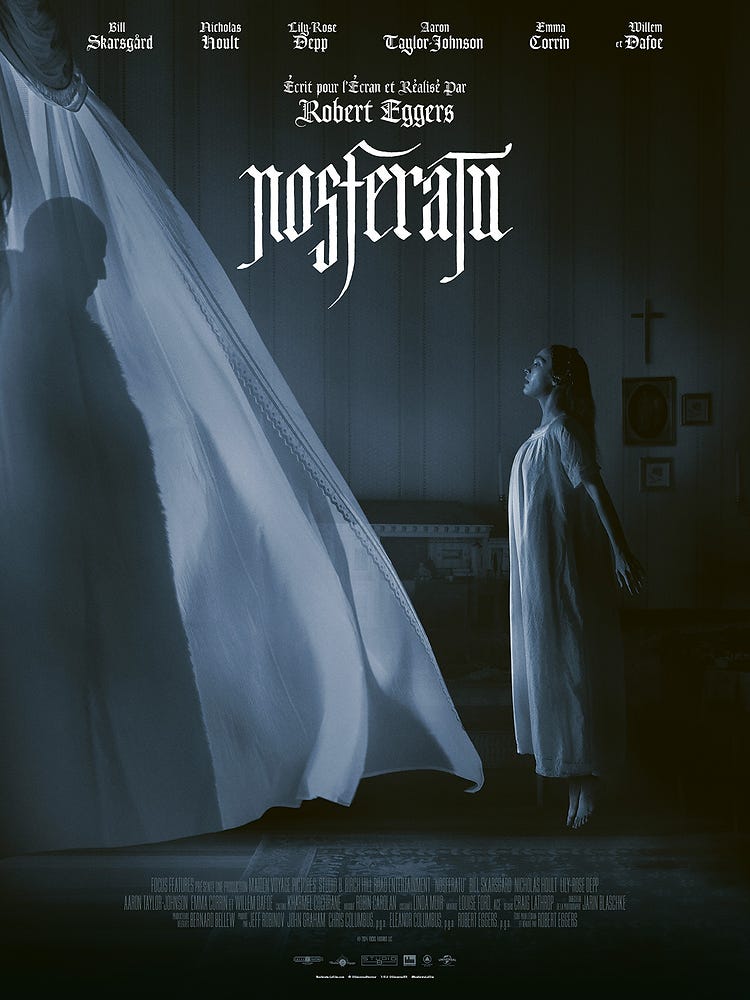

The curtain rises on the early 1830s. A wide-eyed girl (Lily Rose-Depp) pleads for a being to come and ease her loneliness. She seems possessed, perhaps even spellbound, whispering a prayer as though in a trance. And it does the trick, for her cries awaken a slumbering creature who appears to us only as a shadow playing on the curtains: a man perhaps, or at least something like one, with aquiline features, seen only in profile. Outside in the garden, beneath a moonlit sky, this thing demands that Ellen pledge herself to him for eternity. She yields, and he binds himself to her.

Now it is winter, 1838. Ellen is older, and married. She lives in the fictitious town of Wisburg, Germany, with her husband Thomas Hutter (Nicolas Hoult), an estate agent. Keen to gain some financial security following their union, Thomas agrees at his boss’s request to go to Transylvania in the Carpathian mountains. He is told that there lives an eccentric count, Orlok (Bill Skarsgård), who wants to buy a home in Wisburg. This count is old school, and so expects someone from Wisburg to bring the paperwork to him. Ellen isn’t thrilled by the thought of her husband setting off on a six-week work trip across the continent. In fact she begs him to stay. She is haunted, she says, by dreams of Death and unsettled by the pleasure Death gives her in these dreams. Thomas is sympathetic; but refuses. He wants to provide. So he leaves her in the care of his wealthy friend, Friedrich Harding (Aaron Taylor-Johnson), and Friedrich’s family.

And so Thomas sets off, riding east with nothing but some warm clothing and a bundle of papers for the count. But soon he discovers there might be something off about his destination and the man he is going to see. In the foothills of the Carpathian Alps, the local peasantry shun Thomas for saying he intends to meet Orlok. He dreams of Roma, marching through the forest with a stake. Upon waking, he finds the peasantry have gone, as has his horse. He must proceed on foot. And then he encounters an unmanned carriage, which he boards, with trepidation, to Orlok’s castle. Things do not go smoothly.

Nosferatu is based on its 1922 namesake, itself an adaptation of Bram Stoker’s Dracula. Like F.W. Murnau, who directed the ‘22 film, Eggers brings novelty to his take on the vampire legend. The Orlok of Murnau’s film is rat-like and emaciated; it has been suggested Murnau was inspired by corpses seen in the trenches of the Great War. This Orlok, in contrast, is a hulking, mustachioed brute, more a renovation – as I have already said—than an innovation, a nod to the monster of folklore. He also speaks in a reconstructed Dacian, a dead language once spoken west of the Black Sea.

Brute or not, he is compelling, and is the centre of gravity around which everything revolves. He is, in other words, the heart of the film: the plague-carrying monster, the symbol of the Other, the projection of all our darkest, most primal fears and societal anxieties. He is also, in this as in other incarnations, a mirror for repression. He is alluring, dangerous; he breaks taboos and invites us to indulge our desires. The act of biting, which mixes violence with intimacy, is unavoidably charged with sexuality, and here that is made explicit, evoking the crushing the moral authoritarianism of the time in which Stoker was writing.

This particular vampire is also obsessive. Orlok is obsessed with Ellen in a way that transcends mere lust. He yearns for a vital connection with her which, due to his being quite dead, is impossible for him. So he is an avatar, a stand-in, if you like, for the person who longs for what he cannot have, as well as a symbol of the darker side of that desire. Ellen, the object of Orlok’s yearning, is idealised, and so, in a sense, as unreal as the undead Orlok. Orlok’s predation is both a literal expression of his vampirism and a metaphor for how obsessive love consumes and destroys its beholder and, perhaps, its object. Without question Ellen is vulnerable. Everyone is vulnerable when a monster is in town. But she also has power. She is no dehumanised female prey, but a complete human being with violent internal conflicts.

The yearning of the outsider for what cannot be attained seems to be somewhat in vogue. Queer’s William yearns for connection with the enigmatic Eugene; Anora’s Ani yearns to navigate the world on her own terms; The Brutalist’s Laszlo yearns for success and security in the States. But in Nosferatu, we probably don’t want the desirer to get his own way. One reading of the vampire myth is that it represents desire itself, which (as the Buddhists helpfully inform us) is the root of all suffering. The stronger the desire, the greater the suffering.

Speaking of desire—would that every film were as pretty as this one. The cinematography in Nosferatu is stunning. There is a scene—and if you have watched the film you will know which one I mean—in which Thomas, now in the shadow of the Carpathian Alps, stands alone at a crossroads. It is snowing hard, and as a carriage, apparently unmanned, rumbles down the road towards him, he is rendered as a mere silhouette against the pale, ethereal light behind. It is among the most beautiful shots you will see in any film, and not the only sumptuous thing about a film whose costumes and settings—Wisburg, Orlok’s castle, an Orthodox convent—are exquisitely designed and brought to life by Eggers and his longtime collaborator Jarin Blaschke. The acting, too, is roundly brilliant, with Lily Rose-Depp in particular standing out—even for those of my friends who brushed her off as a nepobaby.

Perhaps most impressive of all of Nosferatu is that it is a real story. Horror filmmakers have an irritating tendency to lean on the quiet-quiet-BANG! effect—the jump-scare—or, on the other hand, grisliness and gore. Most of us stopped finding that sort of thing intrinsically interesting when we were kids. This is a film where the tension rises with the pervasive atmosphere of threat, ascending to a peak and dissolving into closure. It is satisfying, as well as fun. And Willem Dafoe stars in it as a slightly mad occultist. I have the sneaking suspicion I might already have seen my favourite film of 2025.

An interesting and engaging take Harry.

I provide a more analytical approach to the film by focusing on the film's deployment of the 'death and maiden' motif that predates postmodernity. My Death Becomes Her may or may not interest you, but I think it supplements your impressions nicely. https://stevenaoun.substack.com/p/death-becomes-her