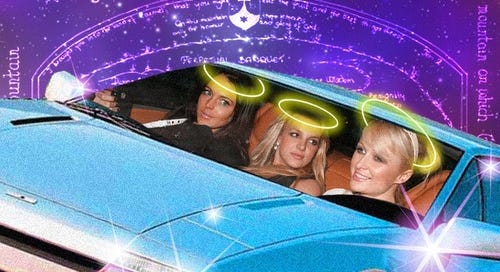

On the evening of November 28, 2006, Britney Spears, Lindsay Lohan, and Paris Hilton emerged from the Beverly Hills Hotel as the paparazzi, who had been camping outside the hotel for several hours, hounded Lohan to find out if Hilton had “actually hit [her]” earlier in the day. The two brushed aside the rumors: “we’re friends,” they insisted, as Britney shyly asked the paps to stop being “pervs” while they attempted to snap photos of her open legs as she got into the car.

The shot captured of the trio as they drove away from the mob of camera flashes was run on the front page of the New York Post the next morning with the headline “BIMBO SUMMIT.” Others brandished it an icon of the descent of “the holy trinity.” The hallowed image has indeed reached a sort of hieratic status, as it has been eternalized by the T-shirts, mugs, posters, and boxer shorts it had been printed on.

Culture writer and astrologer David Odyssey claims that Spears is among the first singers whose fame revolved more around her public image than around the music she made. Similarly, Hilton was once characterized by a journalist as “famous for being famous.” That is, for nothing.

This glorification of nothingness, this separation of fame from any substantial content, from any real skills or talent, is diabolical in nature—if not in the literal sense of the word, then at least in the etymological sense (from the Greek dia-balo, to separate). Yet there is certainly something sinister about the inverted iconography churned out by the paparazzi and tabloid industry. The invasion of these figures’ privacy, the ritualistic humiliation and degradation they undergo, normalizes the desecration of that which is most sacred to the individual.

Internet fodder about celebrities suffering from demonic possession and government mind control abounds. Certainly, most respectable folk will dismiss all this as the stuff of pure delusion. Yet we are left to wonder if perhaps these internet crackpots are onto something—at least in a symbolic sense—upon a closer look at the behind-the-scenes of these stars’ lives. It’s hard to deny how much celebrities like Hilton, Spears, and Lohan have been conditioned from a young age to subjugate their dignity, freedom, and their basic needs as human beings to the fiendish demands of the public, and have been desensitized to being made a spectacle, humiliated, and degraded.

The public’s fascination with spectacles and humans-made-commodities—that is, with the celebrity industrial complex—is undergirded with a primordial sacrificial dimension. As Odyssey once quipped, a fan’s interest in a given singer is distinct from that of the mere “hobbyist” who happens to appreciate the music they make: “fans want god.” Upon realizing that the celebrities we worship are mere mortals, whose star power burns out over time, the public feels betrayed and, in a Girardian sense, wants blood. The ritualistic sacrifice of public figures who we once adored takes on an expiatory effect…though the ceaseless perpetuation of such cycles of adoration and betrayal speak to the fact that said expiation is short-lived…just like the glory of our all-too-human deities.

In her recent autobiography, Hilton wrote about her relationship with Andy Warhol-protege David LaChappelle, the photographer whose 2001 Vanity Fair spread of Paris and her sister Nicky scandalized the public…almost as much as it did their parents. She expressed her esteem for LaChappelle, with whom she discussed “how celebrity worship mimics religious ecstasy,” and whose style was “soaked in spiritual influence—transcendence, forgiveness, enlightenment—and full of religious iconography.”

“Throughout history,” LaChappelle told her, “you always see the celebrated ones—queens and kings, aristocracy, entertainers—seemingly above all others, God-like to the people who celebrate them. People cried at a Beatles concert the same way they cried over a vision of Mary. It’s the same well of tears.”

LaChappelle’s exploration of the intersection between pop and religion often veered toward the blasphemous—whether due to naivete or malintent is hard to say. Warhol—a friend of the Hilton family upon whose lap a 5-year-old Paris once sat at a party as they drew pictures together, telling her parents that “one day this beautiful little girl is going to be one of the biggest stars in the world”—was similarly enthralled by this intersection. But unlike his protege, Warhol’s work was much more cautious. He was no stranger to the ways that our spectacular, consumer society inverted that which is sacred, and the extent to which the “diabolical” forces intrinsic to it are quick to degrade human dignity. He saw through the dangers and emptiness of blasphemy, and made it a point to retain the sanctity of the religious images he depicted (that is, not to let his more lewd content bleed over into them).

Even his more profane works spoke to the vapidness of consumer culture. Take his ironic depiction of the Campbell soup logo. His “Marilyn Diptych,” which commented on how the glory of the celebrities we idolize—unlike God himself—fade over time. Or his superimposition of an ad featuring a bodybuilder with the caption “BE SOMEBODY WITH A BODY” over an image of Christ at the Last Supper consecrating the host, indicating that while the appeal of bodily beauty is fleeting, Christ’s promise of fulfillment to those who consume his body is eternal.

Guy Debord spoke of the “flattening” effect of public spectacles in the age of mass media. Paparazzi photos multiply these spectacles ad infinitum and flatten them out to the point of oblivion—rendering the gratification we seek in them not just empty, but draining, soul-sucking—first for the celebrity whose image is being sacralized, then by her worshiper, who gets trapped in the vortex of consuming commodified depictions of human beings. Similarly, it’s as if Warhol was attempting to communicate to us through the aforementioned pieces that worshipping celebrities, rather than feeding us, eats away at our own souls, making us all the more restless as we oscillate between wanting to consume and sacrifice them.

Warhol never lost sight of the higher ideals his soul yearned for despite being entrenched in celebrity culture, And though far from being a saint, he had a deep reverence for the Eucharist, which he abstained from consuming, as he was well-aware that the state of his soul did not dispose him to do so. This desire to be closer to Christ’s body was intensified after his assassination attempt by Valerie Solanas. His wounded body reminded him of Christ crucified, with whom he sought to experience deeper unity during his time spent serving food to the patrons at the soup kitchen at a local parish.

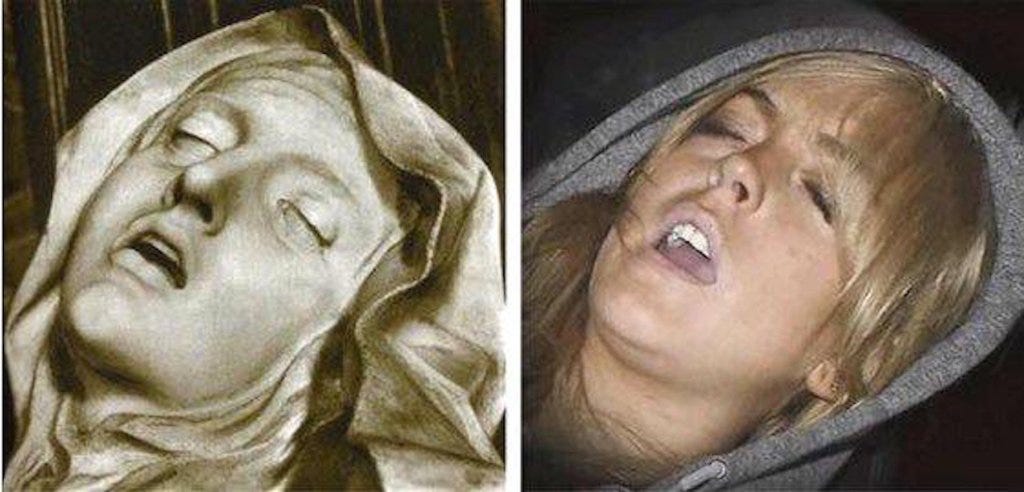

A few months after the Bimbo Summit, the paps snapped a shot of Lohan passed out in her car. Soon after, a meme began floating around the internet that juxtaposed the image of Lohan with that of Gian Lorenzo Bernini’s sculpture of Saint Teresa of Avila in ecstasy. This meme unveils how celebrity culture not only “mimics” religious ecstasy—as Hilton put it—but inverts it. Rather than leading a person’s soul into union with the divine, it momentarily lifts it into the heights of glory only to plunge it quickly down into a dark abyss.

Nine years later, the rumor mills started claiming that she had converted to Islam as pictures emerged of Lohan wearing a burkini and carrying around a copy of the Qur’an. While some found this assertion laughable, I found it to be quite fitting. Islam imagines a God who is absolute Other and who completely transcends the human realm, asking our complete submission to him. Further, Islam vehemently rejects the prospect of idolatry to the point of extreme iconoclasm. Is it any surprise that such a religion would appeal to someone whose life has been ravaged by the idolatrous cult of celebrities?

Our culture which revolves around consumption, celebrities, and public spectacles may be very far removed from cultures that retain a reverence for the sacred. Yet as Warhol intuited, if you look closely enough, you can see the Spirit attempting to crack through it all.