I recently had a riveting conversation with Interintellect founder Anna Gat about Fellini’s La Dolce Vita and Debord’s The Society of Spectacles. You can listen on Spotify, Apple, and YouTube.

I find Anna’s intellectual hunger and optimism to be both refreshing and challenging. As a doomer by temperament and a postmodernist ideologically, I see how much I need people like Anna to temper my pessimism and open my eyes to all of the sources of hope and goodness in our messy pomo landscape.

And so, we’re very excited to announce Cracks in PoMo’s collab with Interintellect. We’ll be hosting a series of 5 salons centered on the theme of “Searching for the Self in an Age of Simulation”:

-The Cult of Celebrity (8/19) feat

and-Behind Body Positivity (8/21) feat

and Abigail Favale-Faith in a Globalized World (8/23) feat John Milbank, William T. Cavanaugh, and

-Reel-y Holy (8/24) feat

and-And lastly, we’ll be hosting an in person salon in NYC with Geoff Shullenberger on how mass media shapes the discourse (date tbd)

Click here to register.

Lastly, check out my reflection on La Dolce Vita in :

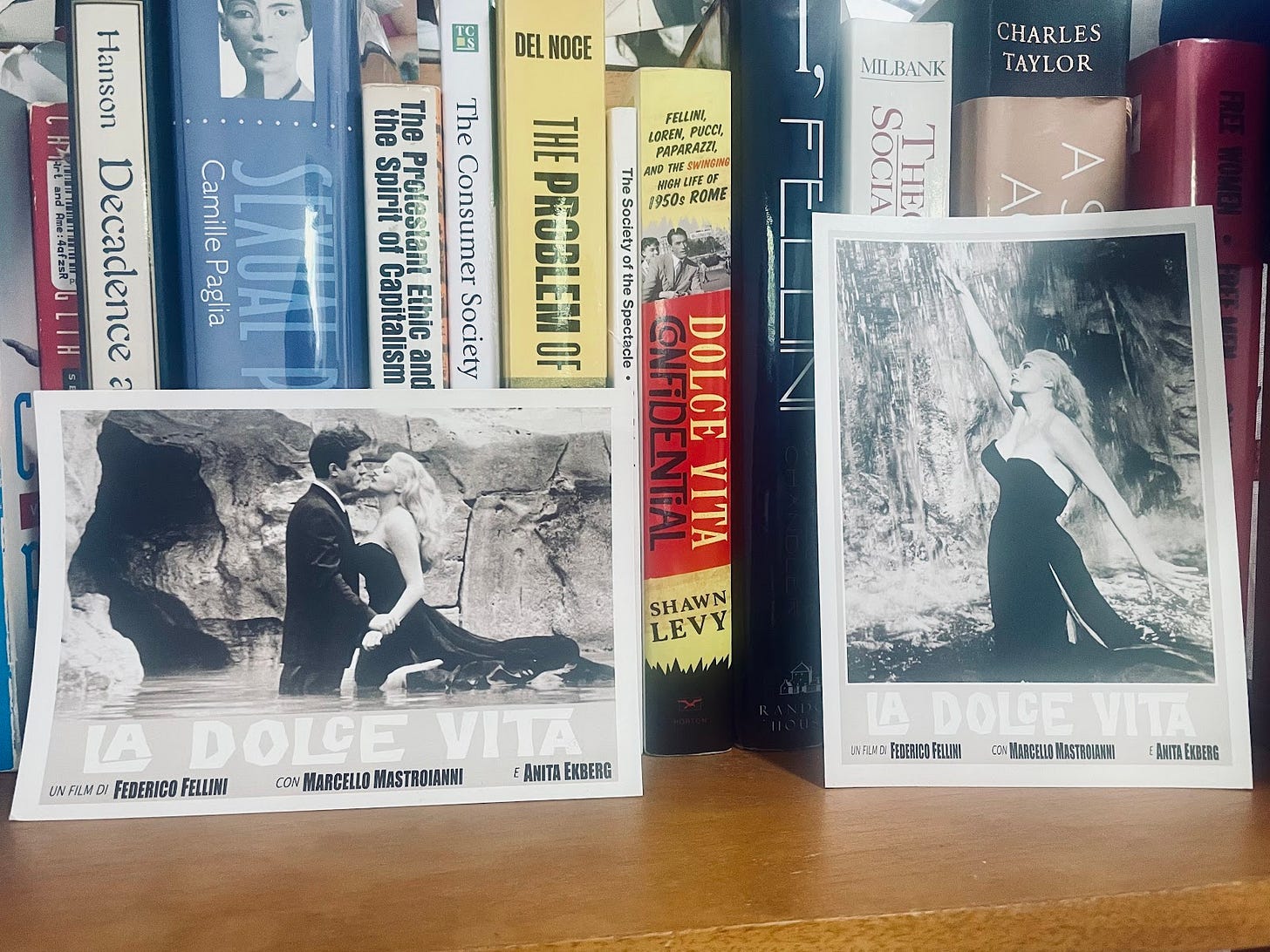

Shawn Levy’s book Dolce Vita Confidential has been a nice break from–and helpful to read alongside–more theory-based texts I’ve been reading by Guy Debord and Jean Baudrillard. The book covers “the swinging high life of 1950s Rome,” using Fellini’s film as a springboard to investigate the shifts in fashion, morals, culture, and economy in post-war Italy. Levy depicts some of the real-life episodes which inspired scenes in the film (namely, Anita Ekberg taking a dip in the Trevi Fountain after a long hot evening on the town, and the sensational media coverage of the Virgin Mary’s appearance in an Umbrian village), asserting that La Dolce Vita is an example of “art imitating life which imitates art.”

He went on to describe how the film drew international attention to Rome’s star-studded Via Veneto, which the film “built” both literally and figuratively. Though the street was already a hot spot for celebrities, paparazzi, and wannabes before the release of the film, Fellini’s mythologization of it expanded its reality to even grander proportions–attracting celebrities from around the world and tourists thirsting for a taste of the “sweet life.”

But in reality, most of the film’s scenes in Via Veneto were actually shot on a replica of the street on set at Cinecittà (Fellini received permission to shoot a very brief scene on the actual street). I couldn’t help but recognize the film’s link to Debord’s theory of “the spectacular society,” which glorifies spectacles that are “all surface” and hollowed out of depth and meaning, as well as to Baudrillard’s insistence that we are surrounded by “simulations” whose “referentials” to reality are increasingly weakening.

Despite Fellini’s insistence that the film was meant to be more of an exploration of the complexity of modern life than a polemic, it scandalized both the left and right upon its release in 1960. Marxists critiqued it for veering too far away from the proletarian commitments of neorealist cinema. And the Vatican condemned it as “highly corrosive” for inciting young people to glorify an “easy, materialistic life without ideals,” and called for “projects of this kind [to] be crushed immediately.”

The film, much like Fellini himself, was misunderstood. Levy does his best to capture Fellini’s playful and unpredictable yet equally humble and endearing persona, citing some of his quirkier quips, including his take on the term “felliniesque” being added to the dictionary: “I always dreamed of becoming an adjective when I grew up!” Dare we hope for more “felliniesque” figures in today’s polarized landscape full of pundits whose views at times feel algorithmically-generated.

Very nicely done. The one time I tried to watch it, I found it crushingly soulless. Perhaps my sense of irony was not sufficiently developed at that time.

On the other hand, I adore Amarcord, so I’m hardly anti-Fellini.