Triduum stuff

Why you should watch Pasolini instead of The Passion; Ratzinger on Nietzsche and Holy Saturday

My case in The American Spectator for why you should watch Pasolini’s The Gospel According to Matthew on Good Friday instead of Mel Gibson’s The Passion:

Pasolini’s closeups on the eyes of Jesus and the people he encounters echo one of the key theological insights of Giussani, who placed emphasis on the way that the disciples recognized Jesus as the Messiah, the “one they were waiting for,” and how they were “won over” by his very “presence” — which although thoroughly human and “natural,” carried within it a divine “correspondence,” meaning that being with him resonated with the deepest needs in their hearts. Giussani posits that the conversion, the true change that happened within those who met Jesus, was born not from their moral effort or force of will, but by the paradoxical joy that sprung from encountering the “supernatural” within the realm of normal, everyday life.

I concede that Mel Gibson’s The Passion of the Christ is a masterpiece. It participates in a long tradition of passion plays, whose merit ought to be judged more so for their liturgical and pedagogical value than their aesthetic quality or capacity to entertain. Gibson brings this tradition to the screen in a way that no one else has, and that no one probably ever will.

That being said, I find that The Gospel According the Matthew manages to convey Pope Benedict XVI’s assertion that “being Christian is not the result of an ethical choice or a lofty idea, but the encounter with an event, a person, which gives life a new horizon and a decisive direction” in a way that the Passion fails to do. The gore and violence of Gibson’s rendering — though on one hand pointing to the love of a God who is willing to take on our sins and endure such horrid suffering — quickly slips into a “moralistic” trap. It risks placing too much emphasis on the sinner rather than on the Redeemer, whose merciful gaze is much more powerful and transformative than the sinner’s remorse for his mistakes and voluntaristic efforts to change. While conversion indeed requires the sinner’s repentance and willingness to collaborate with God’s grace, the real change is accomplished by God himself.

Though perhaps not Gibson’s intention, his grotesque depiction of the suffering that human sin has inflicted on Christ can come off as decadent and self-indulgent. After watching the film, I do indeed feel a sense of remorse for my sins and gratitude for God’s willingness to suffer for me, but rarely do I feel substantially changed by watching it. It fails to incite fascination with Christ and a desire to “leave everything and follow him” the way Pasolini’s film does (though I must admit that some of Gibson’s creative imaginings of Mary’s flashbacks to Jesus’ childhood while watching him being scourged, the way that Mary, John, and the Magdalene accompany Jesus on the Via Crucis, and the dialogue between Pilate and his wife Claudia are indeed quite spiritually moving).

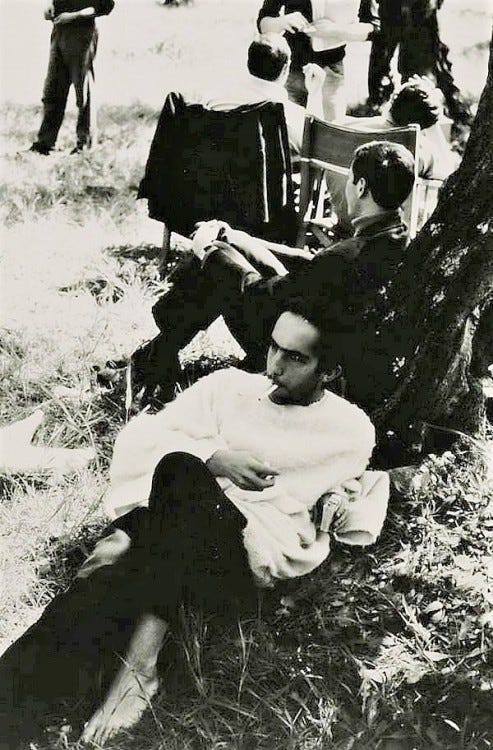

Enrique Izaroqui (Jesus) on the set while filming with Pasolini

Continue reading here.

And a reflection in America Magazine on Pope Benedict’s writings on the “death of God” on Holy Saturday. William Congdon, Slavoj Zizek, John Milbank, and Cornel West get honorable mentions as well:

The late Pope Benedict XVI can be counted among the Christian theologians who acknowledge their indebtedness to the father of postmodern thought. Friedrich Nietzsche’s controversial pronouncement from The Gay Science was the subject of exploration in several of then-Cardinal Ratzinger’s reflections on Holy Saturday. When Nietzsche declares the death of God, he means that the cultural framework that once “propped up” Christian faith and morality has eroded, thus making belief in God irrelevant to life in modern Europe.

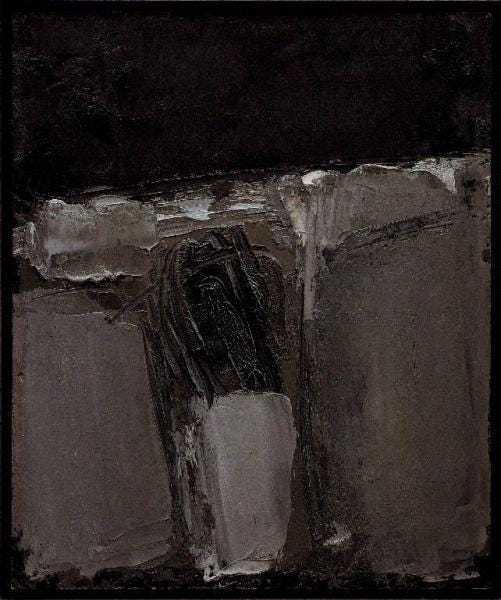

In 1998, Ratzinger’s writings on Holy Saturday, were compiled along with paintings and commentary by the American artist William Congdon in a collection entitled The Sabbath of History. Though Congdon—a convert to Catholicism commonly associated with the Abstract Expressionist movement—never met Ratzinger, both men were deeply attracted to and perplexed by the mysterious events of Holy Saturday.

In the book, Ratzinger describes how Holy Saturday held a particular significance for him, as he was born and baptized on that very day in 1927. His life “from the beginning seemed oriented to this strange chiaroscuro of pain and hope, of divine hiddenness and presence” that he associated with Holy Saturday. It is a day that hangs suspended between the “visible humanity” of Good Friday and the “radiant divinity” of Easter Sunday.

William Congdon’s Crocifisso 46

Continue reading here.

$upport CracksInPomo by choosing a paid subscription of this page, or by offering a donation through Anchor. Check out my podcast on Anchor and YouTube and follow me on Instagram and Twitter.