I first discovered James Baldwin one summer night as I was perusing Netflix. The provocative title, “I Am Not Your Negro,” caught my eye. The documentary displayed a compilation of film clips, footage from the Civil Rights era, and interviews with Baldwin, interspersed with voice-overs by Samuel L. Jackson of some of Baldwin’s writings.

Some Civil Rights activists approached racism as a political problem to be fixed primarily by policy changes. But for Baldwin, racism was a human problem, which he allowed to pierce the depths of his heart. This pain generated in him a set of personal or existential questions about the nature of man and about his own identity: How is it possible for such acts of evil to be perpetrated by other human beings? How could people be so blinded to the humanity of their brothers and sisters? Instead of settling for sentimental or ideological answers, Baldwin dedicated himself to these questions, letting them become the catalyst for a life-long journey.

I was immediately reminded of what happened when I was taught about the Civil Rights movements and the life of Martin Luther King Jr. when I was in second grade. I remember feeling baffled the day we learned about King’s assassination, and I couldn’t sleep that night because of how much I was crying. My mother walked in and asked me what happened. “I don’t understand how they could do that to him. How could people do something so evil to someone so good?” I went to class the next day, hoping my teacher could help me understand this better. She answered by saying, “Well, it’s because racism has been a part of our country for so long. This is why we have to fight for a more just society.”

My teacher didn’t seem to grasp the nature of my question. I understood whyJames Earl Ray shot him. I understood that the legacy of slavery and Jim Crow made some White Americans feel threatened by the idea that Black people should have the same rights as everyone else. I realized that what I was trying to understand is the phenomenon of evil in itself. Why did it exist at all? And where did it come from? When my teacher realized that my question was more existential in nature, she responded by saying, “We can’t really know the answers to those kinds of questions. We just have to try to make the world a better place…” Such a dismissive answer didn’t satisfy me, nor would it have seemed to satisfy Baldwin.

Baldwin’s questions reminded me so much of Fr. Luigi Giussani’s chapter on morality in his book The Religious Sense. Giussani claims morality is less a matter of adhering to rules than an attitude toward truth and reality in general. He situates this within the tension between the questions and desires of the human heart and some ultimate answer. I dedicated my Master’s thesis to exploring Giussani’s moral theology and have never seen an American whose attitude toward morality reflected Giussani’s so closely. Baldwin allowed the evil of lynchings, segregation, and hatred to provoke him with a sense of awe. He addressed the moral evil of racism not just as a problem to be fixed, but as a question to be lived.

Needless to say, Baldwin’s work is challenging to read, especially for Anglos. He often indicated that his intention was to shake up White people’s complacency. But I recommend that we look to Baldwin’s life and works during these tense times, not necessarily because I agree with every conclusion he comes to (I don’t), but because he asks incisive, important, if not crucial, questions that we all need to face.

Baldwin had the ability to go back to basics and face what is most fundamental about the human experience. His profound yet universal questions are capable of crossing through ideological divides, and have the potential to initiate a common journey that invites all humans—Black and White, left and right, atheist and religious—to go deeper into our experience and look more closely at reality.

This is the kind of proposal we need in a culture that is so divided by ignorance, violence, and ideology. I remember scrolling through my Facebook newsfeed the day after President Trump’s State of the Union address and found two things: a series of posts praising or condemning Speaker of the House Nancy Pelosi’s decision to rip up her copy of Trump’s speech. A few days later, the Pope released his Post-Synodal Exhortation, Querida Amazonia. Again, I saw two opinions expressed: praise or condemnation of his decision not to ordain married men as priests and women as deacons.

How can people look at the same reality and come away with such blatantly different judgments? Not only this, but how is it that so many people so easily demonize those who don’t see things the same way as they do? It’s as if we can’t see reality, or our own humanity, anymore. If we asked the questions that Baldwin asked, if we looked at ourselves closely in the mirror, would we be able to demonize “the enemy” so easily? And would we be able to negate our own need for unity with “the enemy?”

Before the pandemic started, I had the chance to present the life of James Baldwin at the New York Encounter with a group of friends. We decided to invite people to speak who are currently living out the ideals Baldwin stood for. Among these speakers were Daryl Davis, a Black man who makes it his mission to befriend Ku Klux Klan (KKK) members, and Christian Picciolini, a former white supremacist. The conversation that ensued between these two was like nothing I had ever seen before. It’s definitely worth watching the whole presentation.

One friend mentioned how he was struck by how countercultural Davis’ attitude was toward the KKK members who hated him. He mentioned the rapid growth of the so-called “cancel culture,” and how Davis’ conviction that every single human being is redeemable, and that it is possible to enter into dialogue with everyone, was truly countercultural. He found this attitude to be so much more attractive, and hopeful. “Why can’t there be more platforms for people to talk like this around the country?” he asked. “If we keep allowing the ‘divide’ to grow, America’s going to drive itself into the ground.”

In order to understand an anomalous “event” like this one, perhaps it would be more valuable not to “expand” it, but to go to the depth of it. What is at the origin of Daryl Davis’ gaze? How is it possible for someone to cross the ghastly divide between himself and someone who hates him for the color of his skin? I can’t say that I am as free as he is. But I do know that I want to be that free. For now, it’s my intention to explore those questions that Baldwin dedicated his life to asking, about America, race, and the human experience. And it’s my prayer that we can all walk together in this journey toward healing and correcting the injustices that continue to plague our nation.

originally published in Faithfully Magazine in November 2020

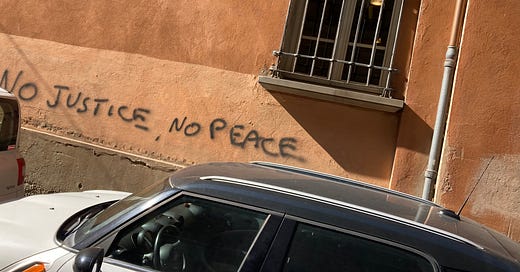

photo taken in Rome

$upport CracksInPomo by choosing a paid subscription of this page, or by offering a donation through Anchor. Check out my podcast on Anchor and YouTube and follow me on Instagram and Twitter.