Happy Advent! Get 40% off an annual subs here.

We’d also like to announce the release of an anthology of essays about Bad Bunny’s career by Rowman & Littlefield, in which I wrote about the cult of celebrity and how Bad Bunny challenges the modern secular vs. religious paradigm.

In honor of the release, here’s a round up of our latest content on the cult of celebrity:

The Shallowness of Celebrity Politics (Law & Liberty)

Al-Gharbi’s work sheds light on the slew of celebrities endorsing politicians under the guise of “giving a voice to the people”—from the likes of Taylor Swift, Beyoncé, Bad Bunny, and Charlie XCX endorsing Kamala Harris, and Hulk Hogan, Jason Aldean, Amber Rose, and Fat Joe endorsing Donald Trump in the latest election. Bad Bunny’s career is particularly emblematic of the fixation with surface-level “symbolic” activism.

In a chapter for a forthcoming volume on the oeuvre of Bad Bunny, I wrote that the 30-year-old Puerto Rican singer is “a master of the spectacle.” His penchant for attention-grabbing promotional tactics, avant-garde fashion, enigmatic usage of social media, scandalous performances, and outlandish lyrics and music videos embodies theorist Guy Debord’s claim that we are living in an age dominated by sensational public spectacles.

…

When someone known for their decadent music and bourgeois lifestyle like Bad Bunny makes such statements about who to vote for and exhorts people to take to the streets to protest, I wonder whether such sensational forms of activism are more likely to yield concrete, grassroots political action or mere symbolic activism that will only serve to foment frustration and social division and thus further weaken the people’s agency, on top of “neutralizing” their concerns by absorbing them into a purely symbolic globalized political discourse.

There is something eerily manipulative about a person or outlet that people turn to for entertainment—especially ones backed by corporate money—presuming to speak not only on behalf of the people, but as authorities on political matters. It’s perturbing that a comedy show like SNL, for instance, takes the liberty to step outside the bounds of its intended purpose (to entertain) and hand its viewers political messaging instead. It reveals that sometimes the “cult of celebrity” literally implies that these public figures assume a quasi-deific power, swaying the public’s opinion not so much because of their qualifications but because of their status alone. While of course celebrities can “use their platform for good,” they can just as easily use it to further ends that do not favor the good of those who hang on to their every word. That those who enjoy Bad Bunny’s music would take political advice from him unveils the totalizing, god-like power such spectacular public figures exercise over the public.

To that effect, sensational moments like Hinchliffe’s vulgar (and rather unimaginative) comments which generate a slew of public statements “#resisting hate” are part of a seemingly continuous cycle of scandals and outrage that pervade the news cycle. Despite the highly moralistic and alarmist language in which such discourse is encoded, in effect, it does little—if anything—to bring attention to pragmatic issues and inspire grassroots action. Though Metropolis may be a work of fiction, the highly performative nature of these cycles and the division they engender feels uncannily manufactured. And even if they aren’t, they do little to bolster the agency of everyday people against those who determine the status quo.

The Bimbo Summit Revisited (Substack)

Culture writer and astrologer David Odyssey claims that Spears is among the first singers whose fame revolved more around her public image than around the music she made. Similarly, Hilton was once characterized by a journalist as “famous for being famous.” That is, for nothing.

This glorification of nothingness, this separation of fame from any substantial content, from any real skills or talent, is diabolical in nature—if not in the literal sense of the word, then at least in the etymological sense (from the Greek dia-balo, to separate). Yet there is certainly something sinister about the inverted iconography churned out by the paparazzi and tabloid industry. The invasion of these figures’ privacy, the ritualistic humiliation and degradation they undergo, normalizes the desecration of that which is most sacred to the individual.

…

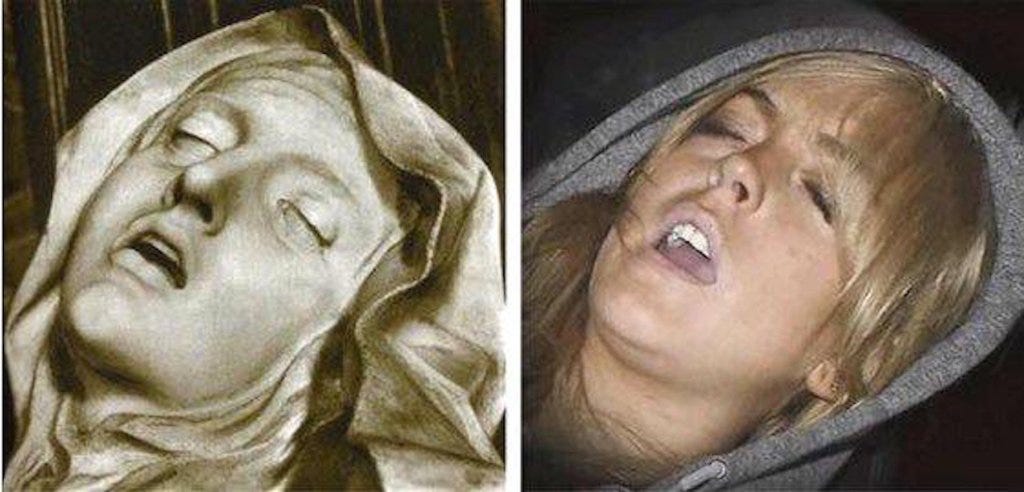

A few months after the Bimbo Summit, the paps snapped a shot of Lohan passed out in her car. Soon after, a meme began floating around the internet that juxtaposed the image of Lohan with that of Gian Lorenzo Bernini’s sculpture of Saint Teresa of Avila in ecstasy. This meme unveils how celebrity culture not only “mimics” religious ecstasy—as Hilton put it—but inverts it. Rather than leading a person’s soul into union with the divine, it momentarily lifts it into the heights of glory only to plunge it quickly down into a dark abyss.

Nine years later, the rumor mills started claiming that she had converted to Islam as pictures emerged of Lohan wearing a burkini and carrying around a copy of the Qur’an. While some found this assertion laughable, I found it to be quite fitting. Islam imagines a God who is absolute Other and who completely transcends the human realm, asking our complete submission to him. Further, Islam vehemently rejects the prospect of idolatry to the point of extreme iconoclasm. Is it any surprise that such a religion would appeal to someone whose life has been ravaged by the idolatrous cult of celebrities?

Our culture which revolves around consumption, celebrities, and public spectacles may be very far removed from cultures that retain a reverence for the sacred. Yet as Warhol intuited, if you look closely enough, you can see the Spirit attempting to crack through it all.

In Concert With the Transcendent (RealClear)

Growing up, religion was more a matter of culture than faith for my family. My true spiritual formation was shaped by celebrity culture. My aunt dutifully took up my father’s request to be my godmother (despite rarely attending church), but her daughter–my cousin–took on the role of my spiritual director, introducing me to the deities that inhabited the pantheon of late 1990s pop culture. She exposed me to the music, TV shows, tabloid magazines, and merch through which I would seek meaning in life. I came to identify with various fandoms, often fantasizing with intense longing about the day I would encounter my idols in the flesh.

On a few rare occasions, this manifested in the form of actually getting to meet them. I remember their physical presence before my little ten-year-old eyes and the intense sensation of being star-struck. But more often than not, this dream was made real through the less intense experience of seeing said celebrities at live concerts.

There was something deeply liturgical about mega-concerts, so much so that they reminded me of the times I had attended church. Yet the spiritual experience of communing with a pop star ravaged my emotions more intensely than any church service had, arousing desires deep inside my soul, and awakening a sense of reverence that I had never felt for God or the images of saints that adorned the church walls and windows.

As I entered my late teen years, I started to feel stunted in my spiritual journey. It turned out that the satisfaction born of worshiping musicians and seeing them perform live was tragically short lived. The excitement fizzled out, and it left me without any means to make sense of the more mundane and arduous aspects of my daily life.

Eventually, I found myself drawn to traditional monotheism, as I came to understand that lasting fulfillment could only come from worshiping the Infinite himself. In place of god-like celebrities, I turned to God and the saints–who didn’t purport to be deities themselves. Unlike over-hyped celebrities, we can find meaning in the stuff of the saints’ daily living, which serves–rather than distracting from the emptiness of our own lives–to help us to find meaning within it.

When looking at pop musicians, the locus of meaning is found not so much in the music they make, but in the hype surrounding their persona–which oftentimes seems to be something separate from the substance of their artistic craft (or lack thereof). On the contrary, the cult of celebrities and the public spectacles associated with it tend to have what philosopher DC Schindler would call a “diabolic” rather than a “symbolic” effect. Modern thought construes reality to be “neutral,” devoid of inherent meaning; meaning is separated (in Greek, dia-balo) from the object in question, as opposed to the classical view which holds that meaning is inherent to the object itself–it is placed together (sym-balo) with the object, forming an integral whole…and when used according to this meaning, brings our wills into harmony with that of the Creator.

Similarly, the French theorist Jean Baudrillard asserted that the global spread of mass media has rendered the modern experience of reality to be more akin to that of a “simulation.” The hype surrounding a mediocre singer stems not from concrete “referentials” (vocal ability, mastery of an instrument, lyrical creativity, etc.) but from a “hyperreal” simulation of greatness concocted by marketing executives. Record labels are in the business of selling a brand–an “experience"–more so than art itself, and offering devotees false “promises.” The simulation of art and beauty fails to satisfy the way real art and beauty do.

That being said, the “form” of a given concert has a significant effect on our relationship with the musicians and the experience of listening to their music. As Marshall McLuhan famously quipped, the medium is the message. Accordingly, the space within which music is performed and the manner in which it is presented determines whether we will be more inclined to perceive the music as a sign that incites us to seek some kind of transcendent meaning, or if we will place all of our hope in the artist and the experience they give us.

…

When reality is separated from its inherent meaning and we are left trapped in a Baudrillardian simulation, we are made painfully vulnerable by the power of mimetic desire. In his commentary on Rene Girard, Luke Burgis breaks down how the major corporations that control the entertainment industry feed off of our mimetic desire, banking on our proclivity to get sidetracked in our pursuit of higher goods by our attraction to following the herd and grasping for goods that–though incapable of fulfilling our ultimate need for meaning–allow us to feel like we fit in with the in-crowd. When any notion of transcendent ideals fall out of our purview, we are left enslaved by the impulse to copy, to imitate others, leaving us frustrated and prone to chaos and violence.

Concerts that center the beauty of the music being performed can break us out of the mimetic cycle, and bring us in touch with the higher ideals that are actually able to fulfill us in a deep and lasting way. Is it any wonder that artists who value their craft so much are often dropped from their labels for refusing to conform to the market’s standards? Is it any wonder that artists who sell their brand rather than artistic integrity, belonging to a fandom rather than just being a mere fan, who can manage to sell out mega-arenas, are given lucrative deals, despite the lack of originality and artistic skill?

While it would seem reasonable to dismiss claims about the music industry’s ties to the occult, we would be right to feel that there is something amiss, a bit sinister, about an artist like Taylor Swift–whose talent, though considerable, is nothing close to the deific–managing to amass fans devoted enough to spend several thousand dollars on a concert ticket.

I can’t claim to be a holy roller. But as much as I may not have renounced my interest in pop music and celebrity culture, I must admit that my perspective has changed. When attending a mega concert, I’m more conscious of what I am (and am not) taking in. There’s certainly something exciting about being in an arena surrounded by other fans who know all the words to an artist’s songs. But I know better than to fool myself into “drinking the kool aid,” and building the experience up to be something it is not.

While the cult of celebrity may not be diabolic in the literal sense, it certainly renders us more susceptible to be taken hold of by our own “demons” within, leaving us defenseless in our attempt to grapple with the emptiness, sadness, and frustration that are part and parcel of the human experience. It certainly pays to pay attention to the devil in the details.