The American writer, editor, and publisher Philip Burnham (1910-1991) was a truly radical Catholic. He wanted to draw from the deepest roots of the Catholic tradition, and he wanted to oppose the injustices of the world at their very roots. This made him resistant to being classified as “right” or “left.” He was opposed both to false understandings of freedom and equality that he saw on the left and to Hobbesian power politics that he saw on the right—as well exploitative and dehumanizing features of industrial/managerial society on both sides. Unlike his much more famous older brother James Burnham, who famously moved from Trotskyism to neoconservatism, Philip saw himself as remaining faithful to the position for his whole life.

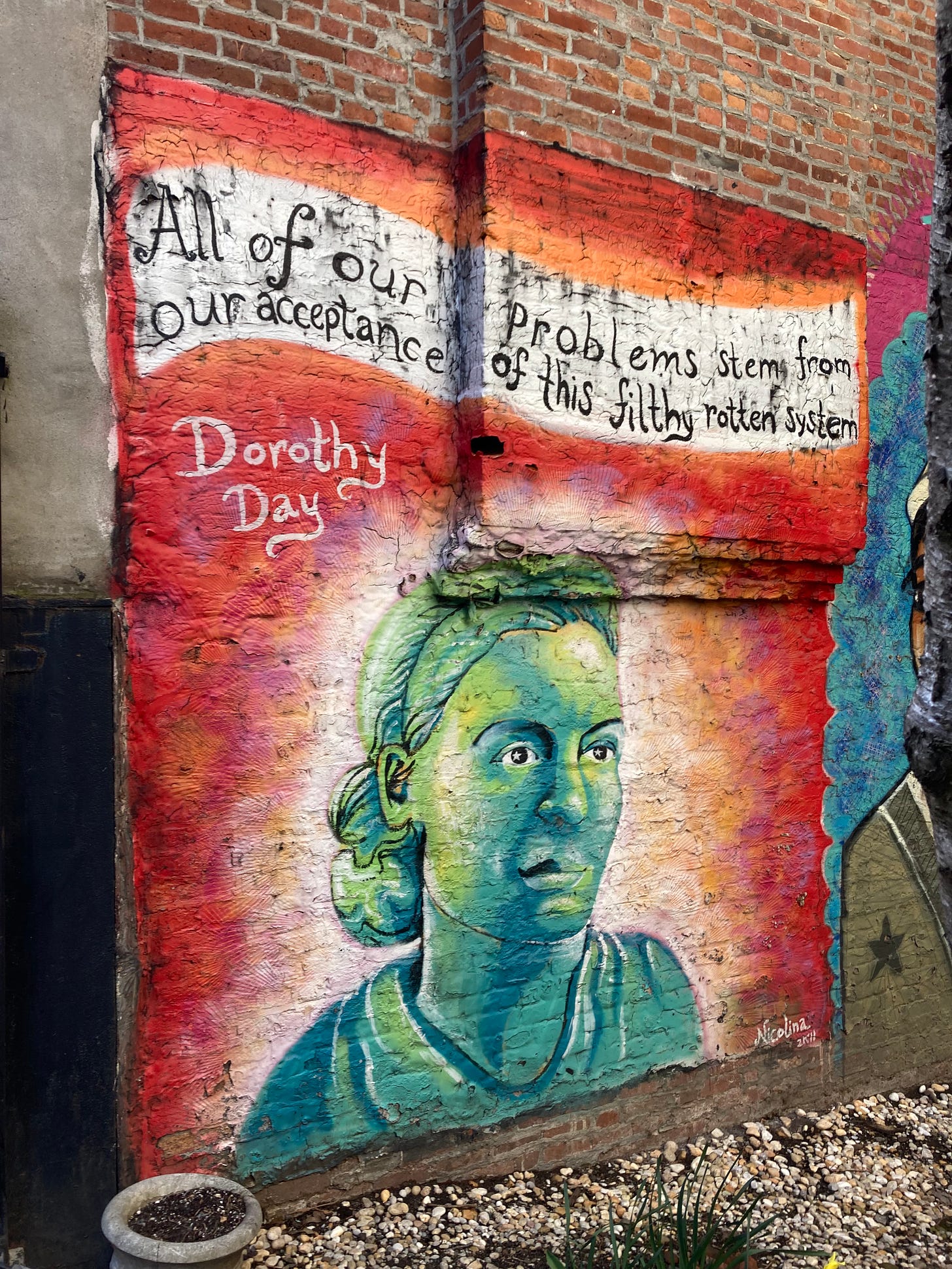

Nevertheless, to outside observers it seemed that Philip, like a Catholic version of his older brother, did move from left to right. In the 1930s, Philip Burnham was a young associate editor at Commonweal. He and another junior editor thought that the editor-in-chief was too enthusiastic about the Franco regime in Spain. So, they bought the magazine themselves, asking the editor to retire. They took a neutral position on the Spanish Civil War, which to many Catholics at the time made Burnham and his associates seem left wing. This impression was strengthened by Burnham’s defense of Dorothy Day and other radical Catholics. But later, after the Council, Burnham appeared to many to be conservative given his opposition to fashionable theological ideas of the time. In the following article, first published in 1973, Burnham explains the consistency of his pre- and post-conciliar Catholic radicalism.

Philip Burnham was my own maternal grandfather. He died when I was little, but I still remember talking to him. I listened to him in awe, and was amazed at his vast knowledge. Unfortunately, at the time I was mostly interested in Swiss Army knives and parachutes and such things, and so that is what we talked about. I wish that I had known enough to ask him about distributism, and about the many Catholic writers whom he had known— Frank Sheed, Maisie Ward, Dorothy Day, Josef Pieper, Evelyn Waugh and many others.

During the allied occupation of Germany after World War II Burnham worked for the Office of Strategic Services, trying to find missing persons who had gone into hiding during the war. To his delight, one of the missing persons he found was the great theologian Romano Guardini. He was also involved in interviewing and recommending political leaders to be invited to help the transition from allied occupation to the new Germany. He was on the team that interviewed Konrad Adenauer and recommended him to be reinstated as Mayor of Cologne after the War. In Adenauer, Burnham saw a model of a Catholic politician who tried to work from the common good from the deepest principles, without submitting blindly to the prejudices of right or left.

-Pater Edmund Waldstein, O. Cist.

When I hear the frost-bitten descriptions of the “old" Catholic Church pronounced today by our more furious co-reformers. I wonder where in the world they found that "old” Church they talk about? When did they or their fathers see the Church helping to pile up the innumerable evils they so angelically associate with our contemporary Establishment? After operating approximately 1,950 years beloved by its members as "the bride of Christ," the "mother of men," and the flowering courtyard of the House of God, now suddenly the Church of any period before October 1962 turns out to have been . . . well, intolerable. If these special friends have thought such deadly thoughts about the Church all along, how did they manage to maintain faith and membership all during that brutal interval before Vatican II . . .beginning, they seem to say, with the Emperor Constantine the Great, reg. A.D. 306-337? How for a fact did these good companions avoid hara-kiri?

Evidently some of my more lethargic friends and I led sheltered lives. It is naively true that we always thought the Catholic Church offered joy and beauty and peace and a better life while maintaining a pretty critical view toward modern institutions and mores. As I read it, from the time of Roger Bacon or at least from the days of Galileo Galilei, Rome was a rather notorious dissident from the trend and tenor of popular science and technology and engineering. By what peculiar persuasion could anyone, after its innumerable quarrels with ancient kingdoms and heresies and modern states and ideologies, saddle the Catholic Church with responsibility for the monolith of frustration which younger people see today in immoral Man, immoral society?

Its official literature is a normal source for discovering the thought and will which the Church has tried to cultivate. It is a painful subject to many people but it is fair to note the simple logical point: the Church in its most magisterial efforts opposed the development of that dominant modern intellectual and political Establishment which so nauseates the current young confronter.

Private Catholic peoples normally can take positions based on personal temperament as well as objective faith with less weighty responsibility. This is a positive attraction that does not fit the picture painted by many who declaim against Catholic "authoritarianism." During the years of Pius XI and Pius XII (1922 to 1958), “This World” was suffering catastrophes which could appeal only to morbid prophets of Apocalyptic Last Days—almost any condemnation of Modern History might have been considered pretty thoroughly justified. Still, in nearly every country there were outstanding Catholics of good enough faith and cheer to see the bad days clearly but nevertheless look for better. A recollection of a few of these thinkers might deepen and widen the perspective of today’s “counter-culture” critics, who seem too often unaware that the ills of modernity were recognized by anyone before last Tuesday.

Thibon.1 Guardini.2 Pieper.3 the Chesterbelloc.4 Ineson.5 All the others ... these European Catholics of the first half of this century were no part of any Establishment. And when the faith and the ways of life they taught crossed the Atlantic, they had their effects. Pre-Vatican II American Catholicism was by no means the simple stuffy thing today’s critics make it out to have been. It was rich, and varied, and deserves to be better remembered.

It has always been an easy truism that the American Church is retarded by its background of frontier and immigrant rudeness. The truism is not solid, but there is a core of validity in it.

This article is supposed to be a protest against the complaint that our Church and religion contributed power and momentum to the pollution and exhaustion of the psychic and physical environment and to the petrification of our dominant institutions into closed machines of frustration and oppression.

Such bitter diagnosis of our ecological sinfulness and of America’s institutional oppression appears to me, comparing them to other regimes of the world sincerely analyzed since Eden, to be exaggerated. But whatever may be America’s true weight of sin. the Catholic element is relatively free, both negatively and positively, from responsibility for bringing down upon the generation now' hopefully maturing the ills they feel they suffer.

Negatively: to a large, tragic extent Catholics have been “outsiders” in the development of this country and even of the entire era of the complexly revolutionary West. This is to some extent a failure of our faith, of course, and of the vitality of our hope and charity. But to what extent it is actually impossible to know. Another cause is the strength of our enemies: ideas having consequences: persons whose humanity and humanness we cannot judge.

Positively: when the American Church and its people overcame passivity and attempted to influence the commonwealth, that influence generally was against the conspicuous evils which current sensibilities deplore.

(Claiming this, one must allow for a long parenthesis. Individual Catholics have exerted important power and influence in American government, economy, and society without exerting much thought-out Catholic “philosophic" influence. At the same time very many of these leaders did splendid works of charity and brought Christian warmth and rightness into large areas of American life. Most of these truly fine men and women lived their lives with fundamental humility (even if they were Knights of Malta . . . or saints, like Mother Cabrini), contributing creatively and unselfishly to the enveloping streams of the country’s culture. They made the stream more living water but they did not for the most part undertake to change its channels.)

The American Catholic tradition can boast of a significant number of reformers who attempted to promote plans and programs and radical changes of life, programs from abroad and programs native born. Here to illustrate I will simply pursue the line of distributism and agrarianism a short step further.

The Catholic Worker and its collaborators have been, and are now, many things to many persons. For a considerable time it was our most famous and most flamboyant complex of work and propaganda. On all fronts it has gloried in being extremist. It is deliberately quixotic, unrealistic, in its own words “fanatical” . . .perhaps, as it would wish, “foolish!" About Church and state, moreover, it has been genuinely and deeply serious. The great Dorothy Day founded it in the depths of the Depression with Peter Maurin, whose humble but persistent boast was to serve as “agitator." Dorothy Day continues now to write marvelous writings with her pen and her actions, and she continues at home in New York and traveling everywhere to see with most effective and activating insight.

There will have to be many full-scale biographies of Dorothy Day before those who have never met her will know her in the least adequately. Peter Maurin spent a large part of his life honing and sharpening and simplifying his message but he has remained a very difficult man to understand. Following Peter required a concentration and depth and simplicity which few of us can generate for more than occasional moments. But those moments, when they came, were experiences not forgotten.

The more recent, more "collaborative" history of the Catholic Worker may make that sound startling, coming from one of its founders. Another distinction he made, reflecting especially upon the writings of Maritain, ought to surprise many recent rebel clerics welcomed in the houses and in the columns of the Catholic Worker:

Laying the foundations of a new social order is the task of the laity. The task of the laity is to do the pioneer work of creating order out of chaos. The clergy teach the principles; the task of the laity is to apply them without involving the clergy-in the application.

Perhaps there ought to be a “Council of Jerusalem“ to get Peter Maurin straight.

The National Catholic Rural Life Conference with its subsidiary branches and organs and publications was naturally agrarian and distributist. but with a visible official moderation. Even the thoroughly "charismatic” personality of Msgr. Ligutti, longtime Executive Secretary, couldn’t quite de-bureaucratize the effort. Still, a ten cent pamphlet published in 1946. For This We Stand, presents a plain and clear and lively position: Pri>pcr aims and methods in farming make possible the acquisition of at least a modicum of security through ownership of productive property, and this in turn favorably affects the human personality. Security must possess a stable base: high wages, the so-called Sixty-million jobs, or even social security by law are not so solid and secure a base for man’s wealth as is ownership of productive property. . . .

Persons and families form communities. Communities help develop families and persons, build up traditions, foster progress, develop civilization and cultures. We have in the United States approximately 78.177 small towns and villages with a population of less than 2.500 each. There lies America’s strength and there is the defense against the atomic bomb. The farmer, his family, the rural parish, the small town and community. . . . The farmer as producer of those things most needed by all human beings must be conscious of his DUTY TO SOCIETY. Healthy soil, good farming practices, quality production not merely for profit but for service as well, should be his aims. . . .

The popularity and gradually the currency and comprehension of these agrarian-distributist concepts of "subsidiarity," “organic development and freedom” and so on have much eroded during the last ten or twenty years. It has almost become improper to worry about state omnicompetence and absurd to trouble your mind about the causes and conditions which have led and may again lead to unpleasant totalitarian regimes. Probably the protagonists of those earlier Catholic policies failed to keep their ideas up-to-date and failed to act in a fashion to beguile America’s difficult younger generations.

Maybe those old parties just didn’t try hard enough. But there is no proof that their concepts and desires could not have been developed to a viable system . . . and cannot so be. "One man. one vote” : a one-210 millionth of a voice on control of the universe is not the maximum personal freedom.

It was a thump I remember surprisingly well when I first became aware of the radical change that had come over some of the best inclined and best endowed of Catholic social-economic leaders. A flash memory, but a surprisingly lasting one remains: driving along fast somewhere out of town in the superb flat farmland of the Santa Rosa Project (the project at the time was run by the brother-in-law of the eminent editor and educator. George Shuster), with Fuji-like Mt. Adams in the distance. As conclusion to some conversation which I don’t remember, one of those unusually attractive and stimulating priests said, somewhat musingly, something like this: "Now we can’t look to working with the ownership of property to bring a decent living and justice to individuals, to all the workers and people generally. They have to get their position by securing a solid democratic voice and the leverage to govern the whole show."

Perhaps I’ve remembered this (vaguely and imperfectly) because it turned out to be an early epitaph for the campaigns of distributism and agrarianism and the methods embodied in the pre-Vatican II papal encyclicals. There is a perfectly reasonable fear, which I share—and think maybe many younger people today do, too—that this rejection involves a particular and ominous breed of One Worldism. The natural ecology, and all the races and tribes of man, and the only and entire economic and political and social enterprise of the earth and nearer stars, are to be taken as one single and unitary productive and distributive machine. The existence and concept of subsidiarity and, indeed, of liberty and diversity, are directly endangered: Gustave Thibon’s “collection of organisms” and most of the secular bones and sinews of the encyclicals are thrown out. The attraction and ability of those Louisiana priests whom it was exciting to have met and spoken with made the ideological thump resound and echo.

Msgr. J. B. Gremillion published a book in 1957 called The Journal of a Southern Pastor. It is the annals, a disconnected kind of diary, of an energetic and important life filled with sympathetic and enlightening vignettes. However it is significantly devoid of practical or philosophic formulations or definitions regarding the enormous social forces and motives and institutions which the author observes. We are left at the mercy of other people’s plans and powers and propaganda projections.

The abandonment of the imaginative and distinctively Catholic view of man and society continued and accelerated through the ’50s and ’60s. Monsignor Ligutti was diverted from the Rural Life Conference to international quasi-governmental efforts at high and more abstract levels; the Conference increasingly turned its vision away from “family-size farms and even smaller units” and from its efforts “to re-establish families on the land.”

Now, of course, there is Agri-Industry, succored by the Bank of America and cheered by modern reformers who love sending International Harvester to the deepest jungles and bringing uniform industrial unionism to every farmer’s back forty. There is still, to be sure, a Christian tradition (or at least a continuing minor theme) of superseding any current massive massing. Whittaker Chambers, for example, built a free farm “in the interstices” of the modern economy. But among Catholics the interest in and vigor of what Peter Maurin called “Communitarian Personalism” are only a pale shadow of what they were in the between-the-War years.

The relations of sociology to religion are at any time—in that time’s contemporary estimation—too obscure to define with much assurance. But that there are living and absolutely necessary relationships between culture and religion we know from faith and reason and the experience of history. Christopher Dawson spent his long and intellectually dramatic career (during several of his last productive years, here in this country) examining and demonstrating the connections. But no scholar is needed to describe for us some of the secular thumps taken by religion during the last decade;

a) Personal sanctification and salvation are not only not the purpose of life: they are separate items from charitable and social duty and the proper destiny of mankind in general.

b) Prayer and action are in a serious sense at odds. They have contrasting generators, characters, purposes and results.

To the extent these frequently heard or assumed propositions are religious and doctrinal a layman is loath to go into them when he doesn’t have to. But to anyone mildly interested in history, several prominent heresies discarded in the past seem again to be disastrously involved. Considered sociologically, this double denial is seen to threaten if not destroy the standing room of the individual person within the embrace of public institutions. We are again persuaded to burn incense before Caesar’s statue.

Obviously, no individual man or woman has the power to take his stand against modern state power or the power of other really important groups and institutions cultivated or tolerated by our sovereign states . . . nor against “the majority” (of Tocqueville) or “the people” (of Rousseau). For this a man and his community need transcendent aid. And the individual and the group have inherently and fully the freedom to seek transcendent protection and assistance . . . or to reject it. It was once the aim of Catholic social thought to help them make the former choice.

Pater Edmund Waldstein is a monk of Stift Heiligenkreuz, a Cistercian abbey in Austria. Read his essay on the strange transition period between the TLM and Novus Ordo Masses, and listen to his appearance on the pod.

During the period after World War I the ability and attraction of French Catholic philosophers and historians, writers and artists, were tremendous—even if now one ought to add in some in-stances. for better or worse. It was exciting for an American Catholic to have those Frenchmen there, albeit across an ocean. Among the near-to-the-war French Catholics, Gustave Thibon makes an interesting and individual example.

The Church from the popes on down at that time was trying to divert society from its wars and exploitations and resentments by many intelligent critiques and exhortations. Gustave Thibon concentrated his determined peasant pressure in the agrarian, distributist, communitarian rhetoric and reform.

A peasant himself, Thibon has no sentimental illusions. There is no pretence that the peasant is morally superior to anyone else. His superiority is purely functional. Unlike the town worker or the civil servant, he is bound to be a realist: his very existence depends upon it. It is the lack o f such realism that accounts for the general decadence of modern society. Hence the need for building upwards, on the secure foundation of the soil. The rest of the book is a development of this basic idea. Socially, what is needed is unity in diversity, and therefore a hierarchical organization of the commonwealth: an aspect of the question which is discussed in the most controversial chapter of all.

[Blurb from Back to Reality]

Thibon’s “nature” is a delicious French combination of the reflectively philosophized and the materially tasted.

Every moral and social romanticism is marked by this frantic parody....Side by side with the classical pharisee, the corrupter of Christian morals, we have the romantic pharisee who corrupts Christian mysticism. . . . At this crisis in the world’s history, when our very reasons for living and acting are called in question. a Nietzsche who attempts the murder of Christian love seems a lesser peril to me than a Rousseau who prostitutes it.

The concept of "quotas” has come dramatically into American sociology’, into parties and schools and suburbs and ecclesiastical councils. As projected thus far in this country it is too obviously negative, mechanical, contradictory and generally against the grain. Nevertheless, most people would agree that there is something to it. Perhaps it is a misdirected or stumbling move toward that “organic social realism.” that politics of “subsidiarity” which the social encyclicals emphasize and Gustave Thibon promoted in his confutations of the democratic mystique.

The polling booth flourishes over the tomb of communal and corporative liberties. . . . It is healthy and necessary that the "masses" should exercise a certain power in the body politic. But in the first place there should be no “masses." In the sense in which the word is understood today. My idea of a healthy people is a collection o f local and professional organisms, highly differentiated and mutually adjusted, but each functioning at its own level. This amorphous mass. brandishing, bear-like, the massive club of its massive claims, is characteristic of a society in the last stages of decadence.

M. Thibon was a radically frank, if not optimistic, fellow: “The thing that amazes me today in every project for reform—individual, social or international—is the ever sharper convergence of the necessary, and the impossible."

The most prominent German Catholics of that time who were rousing interest and enthusiasm among Americans managed, I believe, to work closer to the contemporary history’ tactilely enveloping us. Msgr. Romano Guardini, whose influence was felt primarily pre-World War II. although a series of masterful short volumes constituting a sort of last testament came between the War and the Council, was one. Josef Pieper. post-War and. let us thank the Lord, speaking and publishing now. is a second of those who made us feel the most alive. These writers’ first ability is to begin where their modern audience naturally and necessarily finds itself. The steps and chapters forward can be taken with a warm sense of understanding.

Romano Guardini realized with almost desolate resignation that he lived within a scientific-technological situation which was a quantum leap beyond the old familiar world of Modern Europe. He wrote a book called The End of the Modem World which looked for a tragically bare and lonely defense of Christian life within the narrow bounds of a secular scientific culture of terribly pure spiritual pain. Later. Power and Responsibility: A Course of Action for the New Age sees substantially the same bleak world, but proposes a way of life—perhaps inevitably a "Little Way” of Teresan simplicity—which establishes a position not so perilously near despair. Thus history does not run on its own; it is run. It can also be run badly. And not only in view o f certain decisions or for certain stretches o f the road and in certain areas; its whole direction can be off course for whole epochs, centuries long.

The Establishment has limits: that is the first political and secular consequence of Josef Pieper's most renowned, primarily spiritual proposition. Leisure: the Basis o f Culture is hardly better than half a dozen of his other remarkable compact books, but Leisure claimed the first enthusiastic attention. Effective limits to temporal sovereignty—and to all "useful’* material activities— follow immediately from Pieper’s overwhelming affirmation of man’s basic, highest earthly priority and hope. That is. leisure, celebration, festivity!

Compared with the exclusive ideal of work as activity, leisure implies (in the first place) an attitude o f non-activity, of inward calm, o f silence; it means not being “busy," but letting things happen. Leisure is a form of silence. Leisure appears (secondly) in its character as an attitude of contemplative "celebration" .. . only possible to a man at one with himself, but who is also at one with the world. Those are the “presuppositions” of leisure, for leisure is an affirmation. Idleness, on the contrary, is rooted in the omission of those two affirmations. . . .And thirdly, leisure stands opposed to the exclusive ideal o f work qua social function. . . .

The point and justification of leisure are not that the functionary should function faultlessly and without breakdown, but that the functionary should continue to be a man. . . .

[For men lost in work| to be tied in this way [to intrinsically servile labor] may be the result of various causes. The cause may be lack of property: everyone who is a propertyless wage-earner is a proletarian___ But *o be tied to work may also be the consequence o a ukase in a totalitarian labor state. . . .

In the third place, to be tied to the process o f work may be ultimately due to the inner impoverishment of the individual. Where should we look to end this condition of the practical and spiritual "proletarian"? The soul of leisure, it can be said, lies in "celebration." Celebration is the point at which the three elements of leisure emerge together: effortlessness, calm and

relaxation, and its superiority to all and every function. But if "celebration" is the core of leisure, then leisure can only be made possible and indeed justifiable upon the same basis as the celebration of a feast: and that formation is divine worship. There is no such thing as a feast "without Gods"— whether it be a carnival or a marriage. . . .Divine worship means the same thing where time is concerned, as the temple where space is concerned. . . . And this plot o f land is transferred to the estate of the Gods, it is neither lived on. nor cultivated. And similarly in divine worship a certain definite space of time, specially marked off— and like the space allotted to the temple, is not used, is withdrawn from all merely utilitarian ends. . . .

Sacrifice is the final act of leisure as it is of charity. On the other hand, divine worship, of its very nature, creates a sphere of real wealth and superfluity, even in the midst of the direst material want— because sacrifice is the living heart o f worship....A capital wealth is created which the world of work can never consume, a superabundance o f wealth that cannot be calculated, and that the fluctuations of the world of trade never can disturb—a real wealth, overflowing and superfluous, neither tied nor limited by end or aim: the holiday and feast. . . .

Naturally in this country we knew best among foreign Catholics the English…Overlapping the First War and the careers of these men, came the historic literary protagonists. Chesterton and Belloc. The “Chesterbelloc’’ spurred a long generation of literate pro-and-anti-factions on both sides of the Atlantic to efforts at critical logic and historical realization which men normally resist.

Chesterton loved a good chivalrous Christian battle, as his poetry proves, and Belloc was fascinated by the science of warfare. In this they might rouse the Vietnam generation but hardly delight them: pacifism appears as pronounced among Catholics today as crusading was when Christendom was young. But Chesterton’s and Belloc’s antiestablishmentarianism and their disrespect for the sooty capitalism of their day and for the advancing omnicompetent state should win them present-day votes.

Another phase of this period of British Catholicism is highlighted in the career of a less famous architect-artist, agrarian-distributist, communitarian-pacifist and writer called George Ineson. (Even as so many transatlantic inspirers, Ineson’s Community Journey was brought to this country by irreplaceable, irrepressible Sheed & Ward.)

The Taena Community began as a group of people of varied beliefs and un-beliefs who, obscurely aware o f the sterility and disintegration in modern urban life, were groping after the vital secret which seemed lost, and, not unreasonably, went looking for it in that work of the soil without which all our mechanized complexity would grind to a lifeless halt. It ended (better, began again) as a community of convert Catholics basing their lives, both married and single, on the life-giving center of the Mass and a radical Benedictine pattern o f manual work and prayer, formulated in a specially-devised lay community rule, and lived into reality under the guidance and inspiration of Prinknash Abbey.

In many ways Community Journey is a strange and remote book. Western Civilization is not much relied upon in creating and supporting an intellectual and spiritual framework . . . until the Benedictines. Even they are not embodied by the author in historic Europe but more personalized and at once generalized.

The book is strong and clear particularly about stability—a basic quality of communitarian living which is necessary. I suppose Saint Benedict would declare, for charitable life anywhere: We had begun.... But the difficulty of integrating in face of the inevitable conflict which arises still remains; we try to run away from it. hiding behind a plan or theory which is only, in fact, a mask for the conflict in our own hearts. In this way we arrive at the bitterness of intolerance, religious wars of persecution and hatreds of class, nation and political party: if however, we can face conflict on the level of personal relationships, in the family and small interdependent community, then it becomes part of a creative pattern.

Terrific - thanks much for this