Ray Suarez recently came on the pod to discuss his new book ‘We Are Home,’ which you can listen to on Spotify, Apple, or YouTube. He graciously offered to let us publish an excerpt here on the Substack.

Big stories, involving the futures of millions and the daily lives of nations, can sometimes be elegantly illustrated by tiny events, involving just one person.

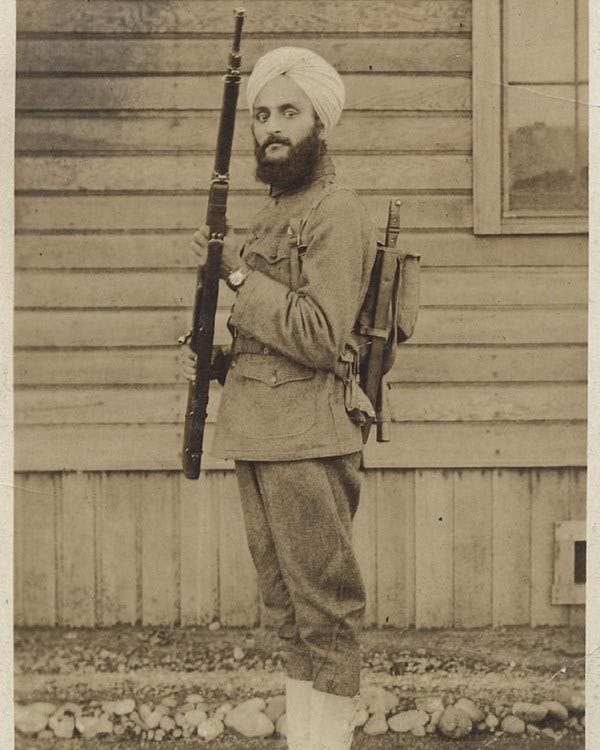

In 1923, the Supreme Court of the United States ruled that Bhagat Singh Thind could not become a naturalized American citizen. Thind was a Sikh from the Punjab province of British India, living in the United States as a student. He had volunteered and served in the US Army late in World War I. He even continued to wear the traditional Sikh turban, covering the long hair Sikh men traditionally avoid cutting. Possessed of a long martial tradition, India’s small Sikh minority formed a pillar of the British-organized Indian Army. Thind became a sergeant, and received his US citizenship when still in uniform, as was promised at enlistment. Then things took a strange turn. The Bureau of Naturalization withdrew the grant of citizenship, overruling a federal district court.

What kept Thind from becoming a citizen even after his service was not his Sikh religion, but his race. The Bureau of Naturalization maintained Thind was not “Caucasian” under the language of the existing statute. He took his appeal to the State of Oregon, only to be opposed by the same Bureau of Naturalization that barred him the first time. This time, along with race, the bureau cited Thind’s political sentiments: his support for Ghadar, a pro-independence movement organized in the Pacific Northwest by Indian migrants. Yet Thind won his appeal, and once again became an American citizen.

Undeterred, the Bureau of Naturalization continued its campaign to keep Thind a resident alien, taking the case to the US Court of Appeals for the Ninth Circuit, which passed the case on to the United States Supreme Court.

The appellate court asked the country’s highest court to rule on very specific questions in this case: Is a high-caste Hindu of full Indian blood...a white person? Also, since a 1917 law—the Asian Barred Zone Act—specifically barred “Hindus,” did that include people who entered lawfully before the law was passed? (Briefs continued to use “Hindu,” and even “Hindoo” as catch-all names for the people of the Indian subcontinent, even though Thind was not a Hindu.)

With all the obsessive parsing of the legal precedent common to the high court, there was a lovely irony embedded in the statute: A faithful Sikh, considered suspicious because he supported evicting his birth country’s colonial masters, might have been saved by a little persecution! The Barred Zone law shutting the door to Indians contained an exception for “all aliens who shall prove to the satisfaction of the proper immigration office or to the Secretary of Labor that they are seeking admission to the United States to avoid religious persecution in the country of their last permanent residence, whether such persecution be evidenced by overt acts or by laws or governmental regulations that discriminate against the alien or the race to which he belongs because of his religious faith.”

The high court had already turned back a Japanese petitioner seeking naturalization in its precedent-setting ruling in Ozawa v. United States, citing the racial exclusion contained in the plain language of existing laws when rejecting the citizenship position of Takao Ozawa. Writing for the court, Associate Justice George Sutherland noted, “The appellant is a person of the Japanese race, born in Japan....Including the period of his residence in Hawaii appellant had continuously resided in the United States for twenty years....That he was qualified by character and education for citizenship is conceded....The appellant in the case now under consideration, however, is clearly of a race which is not Caucasian, and therefore belongs entirely outside the zone on the negative side.”

Thind identified as “an Aryan,” that is, a descendant of the ancient civilizations of northern India and Persia. That meant Thind was “white,” according to the racial science of his day. One might have assumed, if Ozawa was not allowed citizenship because of his “not Caucasian” status, Thind would have to meet the technical definition set out by the high court. The justices had no problem contradicting themselves.

The high court ruled Thind would not be considered white in the eyes of “the common man,” and his petition for naturalization was denied. The Punjabi doughboy, defeated in his attempt to become a citizen of his adopted country a third time, did not go down in defeat alone. Some fifty other Indians who had been naturalized also lost their citizenship when the nine justices unanimously ruled against Thind.

Rather than engage in tricky biological or historical speculation about the meaning of the term “free white persons,” the opinion used the definition an average American would use for “white” or “Caucasian.” In the court’s estimation, racial theories and the history of Indo-Aryan Asia not-withstanding, Bhagat Singh Thind might have been a free person. He just was not white.

In much of the modern era, Americans have spoken with great affection of the country’s immigrant past. They like to think that throughout the nation’s history, immigration was the engine driving the country’s unique diversity. To be sure, that is true. In practice, however, only white immigrants were able to become citizens of the United States for the country’s first century of existence. From the signing of the Declaration of Independence until 1870, only white people who made it to the US had any hope of becoming American citizens. In 1870, with the passage of the post–Civil War amendments to the Constitution, “aliens of African nativity and persons of African descent” were added to “free white persons” to become the only two categories of people who could be naturalized under law.

Add to those statutes the Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882, and the practice of gradually raising barriers to Japanese migration and naturalization, and Sikhs, Hindus, Buddhists, and Muslims around the world were largely blocked from naturalization, not by virtue of their religion, but by virtue of the believers’ races and countries of origin.

It must be noted that what people meant by commonly used terms like “race” and “white” does not match contemporary definitions. The Dillingham Commission’s reports of 1911, funded by Congress in an attempt to create a framework for debate over limiting immigration from Europe, used a vast array of “racial” definitions for people who in 21st-century America are simply called white. The reports, which over the course of the commission’s work ran to more than forty volumes, defined a number of distinct races, including: “Africans” (Black) and “Cubans” (separate and distinct from “West Indians”), and groups that would later simply be called “white”: “Dalmatians” (from the Adriatic Coast of what would become Yugoslavia), “Ruthenians” (Eastern Slavs from Poland, the czarist empire, and Ukraine), “Scotch,” and “Welsh,” among others.

After decades of assimilation and acculturation, Americans would think of almost all these people as “white.” The Dillingham Reports fretted about so-called New Immigrants and “the extent to which recent immigrants and their children are becoming assimilated or Americanized,” as compared to the descendants of “Old Immigrants” who had “overcome” barriers to assimilation, “while the racial identity of their children was almost entirely lost and forgotten.” These conclusions were no small matter as Congress looked for a way to limit immigration: Historian Katherine Benton-Cohen noted in her book Inventing the Immigration Problem, “Within a decade almost all of these policy initiatives (meant to reduce immigration from the ‘races’ of southern and eastern Europe) were implemented into law....The commission’s reforms effectively ended mass immigration from 1924 to the passage of the Hart-Celler Act of 1965.” Implicit in Congress’s assumptions in the early 20th century was this: Some people can, over time, become just like us. Others can’t.

Using race to shape immigration standards—even as the definition of the white race kept changing—ended up having a religious effect. Into the 20th century, this statutory language around race resulted in only a narrow band of the world’s religions being widely and openly practiced on US soil. Though American religion was stunningly diverse and endlessly inventive, in the main it consisted of a wide range of Protestant Christianity, Catholicism, and Judaism as practiced by the immigrants of Eastern Europe and descendants of the Iberian Jewish diaspora. Beyond that, there were tiny, vestigial Muslim communities scattered across the country.

Though it is rarely acknowledged in the way we teach history, Muslims lived in the United States from the earliest decades of the colonial period. They were West Africans, whose ancestors converted to Islam centuries earlier and were brought to the western hemisphere to work as slaves. Slaveholding Americans intensely and systematically suppressed the home languages, cultural practices, and the original religions of their human property. An indigenous Islam tied to the cultural memory of Africa could not take root in the young United States.

So:

Immigrants were white.

Whites were from Europe.

European immigrants were almost uniformly Christians and Jews.

So, by the mid-20th century Americans were almost exclusively Christians and Jews.

Almost all African slaves and their descendants were converted to Christianity.

Thus, even most non-white Americans were Christian as well.

The exceptions began slowly in the last years of the 19th century and the dawn of the 20th. A tiny trickle of immigrants arrived from the Ottoman empire, from modern-day Turkey, Syria, Lebanon, and Palestine. Many of those immigrants, mostly men, were Muslims. Yet even Ottoman immigrants were mostly Christian, so that a century later the majority of Arabic speakers in the US, from Syria, Lebanon, Palestine, Turkey, and Iraq, were Christian. In an appeal similar to the Thind case, courts ruled in Dow v. United States in 1915 that immigrants from “Syria” in the Ottoman empire were white under law.

Excerpted from ‘WE ARE HOME’ by Ray Suarez.

Copyright by Ray Suarez. Used with permission from Little, Brown and Company, an imprint of Hachette Book Group. All rights reserved.

Please consider signing up for a paid subscription to this page for more riveting content.

If you’re new to Cracks in Pomo, check out the About page or read up on our Essentials. Also check out our podcast on Spotify, Apple, and YouTube and follow us on Instagram and Twitter.

MASA tortilla chips by Ancient Crunch is offering our followers 10% off their order with the promo code CRACKSINPOSTMODERNITY. Click here to redeem.

photo courtesy of the National Parks Service