Some throwbacks to enrich your experience of the Easter Triduum…

My Houellebecqian Good Friday miracle

Good Friday and Easter Sunday are amongst the holiest days of the year for Christians. They represent two opposite poles of suffering and hope, of death and new life. Besides contemplating the Paschal mysteries, I spent these days contemplating the works of Michel Houellebecq, the French troubled literary genius.

After finishing his novel Submission last year toward the end of Lent, I anxiously awaited the release of the English translation of his latest novel Aneantir (Annihilate), which was initially set for the summer of 2022 but has been pushed back indefinitely.

What business does a devoted believer like myself have reading novels written by an agnostic Frenchman — which consist of irreverent humour and flagrantly pornographic sex scenes — during the most sacred moments of the year? Well, Christ’s “submission” to God the Father’s will and his readiness to be “annihilated” by his detractors forged a paradoxical unity between these seemingly irreconcilable, markedly Houellebecqian poles.

Surely, I say this in jest. Such an excuse for reading Houellebecq may sound like an unconvincing exercise in Jesuitical casuistry. In all seriousness, though Houellebecq is not afraid to enter into the “abyss” of the human condition. His willingness to confront the deep-seated nihilism that pervades the West in his works has brought him to the brink of faith. He often writes — both in his novels and essays — of his esteem for the moral and social values linked to Christianity. For this reason, reading his books provides believers with challenging insights.

On Good Friday of 2023, my understanding of the relationship between Houellbecq’s works and the Easter Triduum was made more profound, more personal. After walking in a Way of the Cross procession from Brooklyn into lower Manhattan, I made my way uptown to a Tridentine Passion service in Midtown. I got distracted en route by a “subversive” bookstore filled with young people decked with nose rings, purple hair and gender-nondescript clothing. I quickly put out my Lucky Strike, rubbing it into a fire hydrant until I had annihilated the last orange spark (tobacco is the one indulgence I allow myself whilst fasting). As I walked in, I hesitantly asked the sales clerk, who was aimlessly scrolling through Instagram whilst manning the register, to help me find a book.

“Sorry, we don’t have a computer database” — how countercultural, shocker — “but you can look in the fiction section.” I should have known better than to presume to interrupt his scrolling session. As I began searching, I happened upon a thick, square-shaped book with Houellebeq’s name written along the top in all lowercase characters. It was lying on the “Featured Books” table, with annihilate traced in a blood-red tone across the middle.

“Damn, this is out already?” I exclaimed to the clerk, baffled by the fact that I was not aware that the long awaited novel had already been released. “I didn’t hear anything about it online yet.”

“Yeah,” he muttered without looking up from his screen. “We just got that one copy in yesterday.”

On my way home from the church service, I started searching the web ravenously for information about the book’s official release date. The English translation was unavailable on all major book vendors’ websites, and no news about it was to be found anywhere. Weird …

As I spent Holy Saturday devouring the novel, it quickly became clear to me that there was no way that this copy could be an official translation. Littered with literal translations, it read like it was put through Google Translate. Could it be, I wondered, that the apathetic clerk accidentally put a galley copy of the book out for sale? I never thought I would say this, but thank God for millennial laziness.

On Easter Sunday, I gave praise to God — becoming the first person in the anglophone world to read Aneantir was evidently his reward to me for “submitting” to his will on Good Friday by following the cross, the instrument of his “annihilation”, over the Bridge. I carried the book with me throughout Easter week, ostentatiously displaying it on the table where I was sitting at a coffee shop and posting pictures of myself reading the book on Instagram … much to the envy of my followers — some of whom offered to buy it off me. But no. This was my reward from the Almighty, who had smiled widely upon me and showered me with this gift.

Much like Houellebecq, I’m going a little too far — I have a taste, like him, for the decadent, the hyperbolic. The true gift in reading Annihilate is not so much that I am the only special snowflake reading it in English right now, but rather the content of the book itself.

Continue reading at The Critic.

Also check out my review of the latest novel byDaniele Mencarelli, Houellebecq’s non-nihilistic counter-part.

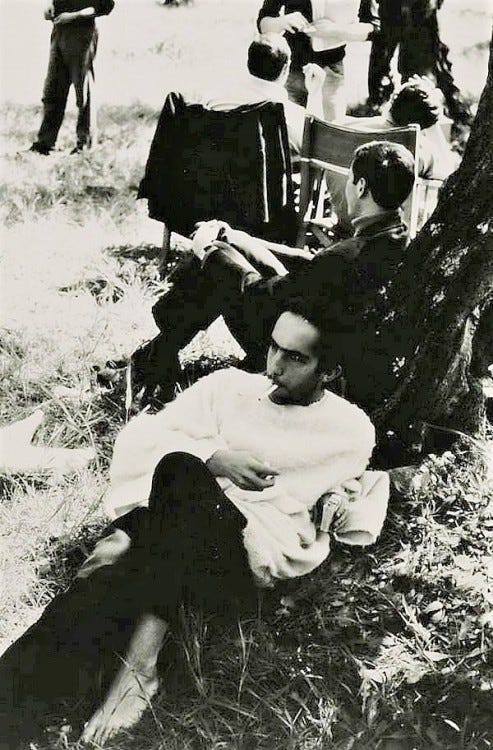

Why you should watch Pasolini’s The Gospel According to Matthew (perhaps instead of watching The Passion of the Christ):

Pasolini’s closeups on the eyes of Jesus and the people he encounters echo one of the key theological insights of Giussani, who placed emphasis on the way that the disciples recognized Jesus as the Messiah, the “one they were waiting for,” and how they were “won over” by his very “presence” — which although thoroughly human and “natural,” carried within it a divine “correspondence,” meaning that being with him resonated with the deepest needs in their hearts. Giussani posits that the conversion, the true change that happened within those who met Jesus, was born not from their moral effort or force of will, but by the paradoxical joy that sprung from encountering the “supernatural” within the realm of normal, everyday life.

I concede that Mel Gibson’s The Passion of the Christ is a masterpiece. It participates in a long tradition of passion plays, whose merit ought to be judged more so for their liturgical and pedagogical value than their aesthetic quality or capacity to entertain. Gibson brings this tradition to the screen in a way that no one else has, and that no one probably ever will.

That being said, I find that The Gospel According the Matthew manages to convey Pope Benedict XVI’s assertion that “being Christian is not the result of an ethical choice or a lofty idea, but the encounter with an event, a person, which gives life a new horizon and a decisive direction” in a way that the Passion fails to do. The gore and violence of Gibson’s rendering — though on one hand pointing to the love of a God who is willing to take on our sins and endure such horrid suffering — quickly slips into a “moralistic” trap. It risks placing too much emphasis on the sinner rather than on the Redeemer, whose merciful gaze is much more powerful and transformative than the sinner’s remorse for his mistakes and voluntaristic efforts to change. While conversion indeed requires the sinner’s repentance and willingness to collaborate with God’s grace, the real change is accomplished by God himself.

Though perhaps not Gibson’s intention, his grotesque depiction of the suffering that human sin has inflicted on Christ can come off as decadent and self-indulgent. After watching the film, I do indeed feel a sense of remorse for my sins and gratitude for God’s willingness to suffer for me, but rarely do I feel substantially changed by watching it. It fails to incite fascination with Christ and a desire to “leave everything and follow him” the way Pasolini’s film does (though I must admit that some of Gibson’s creative imaginings of Mary’s flashbacks to Jesus’ childhood while watching him being scourged, the way that Mary, John, and the Magdalene accompany Jesus on the Via Crucis, and the dialogue between Pilate and his wife Claudia are indeed quite spiritually moving).

Continue reading at The American Spectator.

Also check out my audio presentation on Pasolini’s The Gospel and my take on the English dubbing of the film.

And while you’re at it, check out Carlo Lancelotti’s take on Pasolini, Secular Power, and the Church, and Stephen’s take on Bad Bunny and Pasolini.

On Pope Benedict’s writings on the “death of God” on Holy Saturday. William Congdon, Slavoj Zizek, John Milbank, and Cornel West get honorable mentions as well:

The late Pope Benedict XVI can be counted among the Christian theologians who acknowledge their indebtedness to the father of postmodern thought. Friedrich Nietzsche’s controversial pronouncement from The Gay Science was the subject of exploration in several of then-Cardinal Ratzinger’s reflections on Holy Saturday. When Nietzsche declares the death of God, he means that the cultural framework that once “propped up” Christian faith and morality has eroded, thus making belief in God irrelevant to life in modern Europe.

In 1998, Ratzinger’s writings on Holy Saturday, were compiled along with paintings and commentary by the American artist William Congdon in a collection entitled The Sabbath of History. Though Congdon—a convert to Catholicism commonly associated with the Abstract Expressionist movement—never met Ratzinger, both men were deeply attracted to and perplexed by the mysterious events of Holy Saturday.

In the book, Ratzinger describes how Holy Saturday held a particular significance for him, as he was born and baptized on that very day in 1927. His life “from the beginning seemed oriented to this strange chiaroscuro of pain and hope, of divine hiddenness and presence” that he associated with Holy Saturday. It is a day that hangs suspended between the “visible humanity” of Good Friday and the “radiant divinity” of Easter Sunday.