“What if I don’t want to get married?” I, a shy and awkward seventeen-year old high schooler, asked the rector of my archdiocese’s co-cathedral, where I was a parishioner. A joint presentation on rites of passage, marriage, and vocation by the priest from my church and a rabbi from a nearby synagogue had just concluded and I had taken the opportunity to corner Father with a pressing question. To my disappointment, his response was a silent gesture toward his roman collar with his index finger.

At the time, I was unable to say why I felt so disappointed with this response, but I somehow knew that the question I had was of great importance, and the response felt a little too facile, too easy. Many years later, I see that the response I wanted was for Father to ask me, “why not?” I wanted to have someone I could open up to about the fears I had of family life, the mix of powerful emotions I had as a result of my parents’ divorce, the isolation and self-loathing I experienced in reaction to a sexuality that I was thoroughly unprepared to face. I was alone and afraid, and I was trying to call out for help, and the Church wasn’t there when I needed it.

Although the Catholic Church has a strong tradition of celibacy in the priesthood and consecrated religious life, it struggles to recognize and address the needs of laity who are unmarried. For a host of reasons ranging from same-sex attraction to economic limitations to psychological or physical illness to plain old bad luck, faithful Catholics who have not entered into either matrimony or consecrated life are frequently overlooked or treated as a problem in need of a solution.

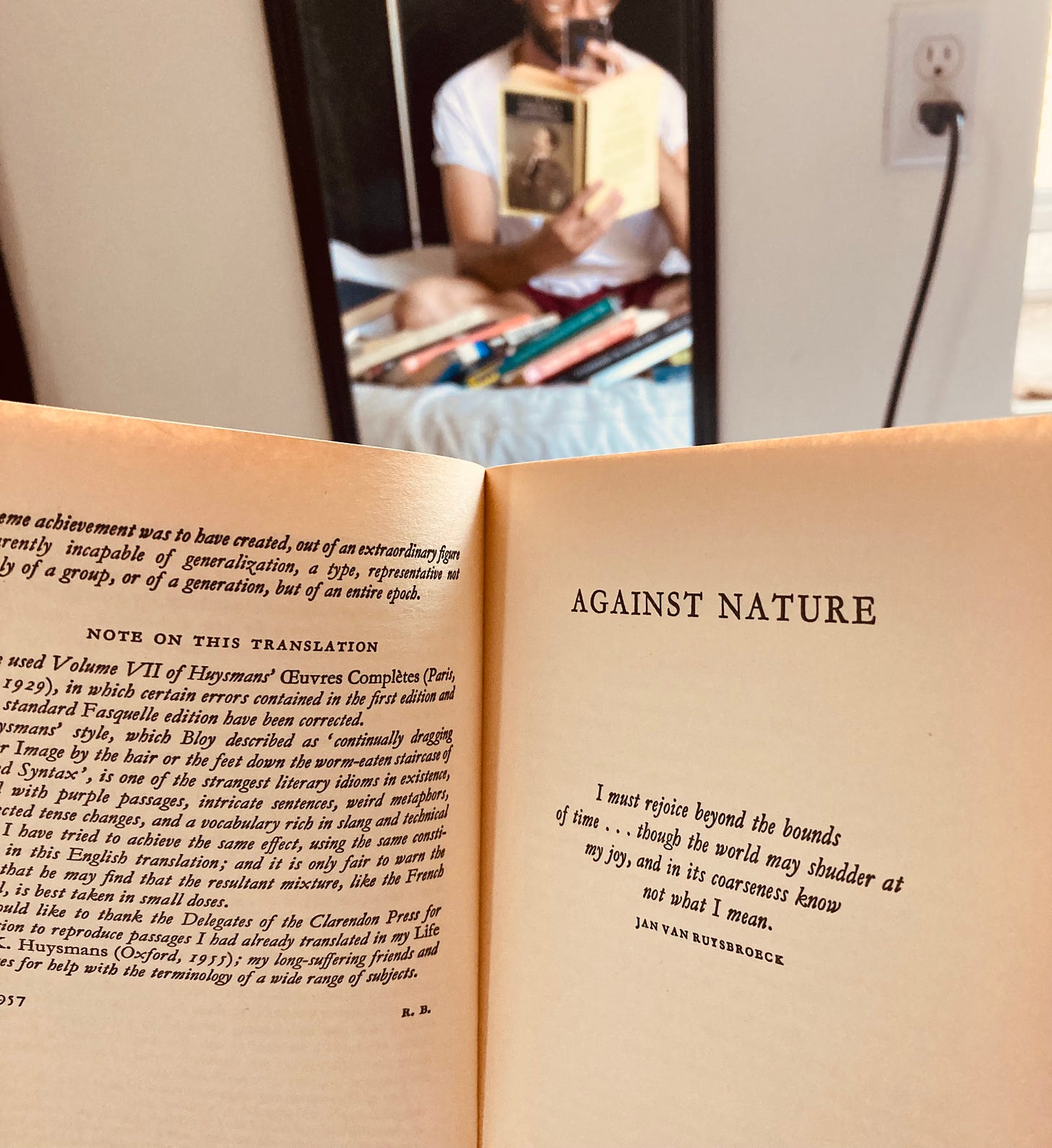

The late 19th century French novelist J.K. Huysmans fills this silence with a response in his series of four novels that detail the conversion of his autobiographical protagonist, Durtal. The first novel in the series, Là-Bas, addresses the occult activities and Satanic worship practiced by disaffected aesthetes of 1880s Paris and culminates in Durtal attending a Black Mass with his lover Madame Chantelouve, a practicing Satanist. Next, in En Route, Durtal experiences an unfolding conversion to Catholicism, fueled and nourished by the aesthetic and spiritual power of Catholic art and liturgy, particularly Gregorian chant. This conversion leads him to making a retreat at a Trappist monastery, where he at last makes a confession and renounces his sins, particularly the sacrileges and adultery of his affair with Mme. Chantelouve. La Cathédrale, the third novel, is a detailed and extended meditation on the beauty and symbolism of the cathedral in Chartres, where Durtal has relocated. Here, Durtal’s aesthetic experience of faith comes into full bloom in such great detail that readers of the novel have used it as a guidebook to the cathedral since its publication. Lastly, Durtal finds fulfillment in L'Oblat, where he at last has settled into his vocation as an oblate of the Benedictine abbey at Val-des-Saints in Burgundy.

Durtal’s path to holiness is perhaps even more timely today than it was at the time Huysmans wrote his novels. In our age of alienation from and distrust of dogmas and institutions, renewed and “remixed” versions of witchcraft, spiritualism, transhumanism, and Nietzschean vitalism are shaping the religious practices across society, including among self-identified and practicing Christians, as Tara Isabella Burton has observed in Strange Rites.

This seeking and remixing reveals a deep fundamental need for transcendence within the hearts of people across religious practices, socioeconomic groups, sexual identities and political affiliations. Whatever belief systems have arisen in the ebb of post-Christian America are not the hard materialist atheism of Christopher Hitchens and Richard Dawkins. To answer Philip Larkin’s question, “And what remains when disbelief has gone?” it seems more likely to be an experience of promise in technology that will ward off a climate apocalypse, or the nearly-religious communal energy and excitement of Taylor Swift’s Eras Tour, or the urging of young men to become “alphas” by manosphere influencers like Andrew Tate than it is to be groups of crotchety antitheists quoting God Is Not Good.

Occasionally, these disaffected seekers, like Durtal, discover the power and beauty of Catholic art, liturgy, and music. My own path back to the Church was cleared by a woman I was hooking up with years ago who asked me if I wanted to go to a church on the Upper West Side of Manhattan to hear the choir. For some reason, I said I did, and so we went to Mass where I heard Gregorian chant and polyphony in its liturgical context for the first time ever. That experience was enough to make me return the next Sunday, and the next Sunday after that. That initial experience of beauty led me back to the Church, where I eventually joined the choir and came to love Christ, the Church, the Scriptures, and the social teachings of the Church handed down to us over the centuries.

Powerful as this aesthetic experience of the Church is, however, it is not sufficient. The paradox of Huysmans’s novels is the inward progression of the action across the series. The intense sexuality, wizardry, and Satanism of Là-Bas gives way to the beauty-seeking that draws Durtal into encounter with the sublime in the liturgy. Despite the significance of this aesthetic experience, Durtal doesn’t remain as a sort of liturgical tourist or spectator attending a musical performance. It instead feeds a faith that grows in him and leads him to the Trappist monastery where he confronts his sins, experiences remorse, and makes his confession.

As with Durtal, so with today’s remixers and seekers. The beauty of Catholic music, liturgy, and art still has power to touch hearts that crave transcendence and enchantment, the full expression of which is the conversion, repentance, and growth in holiness of a heart seeking not merely a beautiful piece of music or art, but instead seeks to know and love Christ.

Paradoxically, Durtal’s conversion deepens rather than diminishes the importance of beauty in the spiritual life. His spiritual movement directs him away from the noise and activity of Paris to an anxious confrontation of his inner self in the monastery and onward to Chartres, where he experiences a “sudden transition from a stinging north wind to a velvety caress of air” upon entering the cathedral. He is now in the quiet and beautiful house dedicated to the Blessed Virgin Mary, whose maternal guidance and love he recognizes as that of a benevolent Mother who “preserve[s] him from unforeseen risks, from careless slips, from great falls.”

La Cathédrale is, in this sense, the story of an incubation, a man growing and spiritually maturing in the contemplative Marian setting of Chartres. The power of the cathedral’s windows, porches, and soaring ceilings, and the companionship of an elderly priest and his housekeeper Madame Bavoil, serve to cultivate in him a love of the Virgin and of quiet, humble worship. Drawn deeper into Mystery, Durtal finds himself called away from Chartres. As he bids farewell to his companions, Madame Bavoil says, “We will pray with all our might…that God will enlighten you and show you your vocation.”

And so He does. Durtal, the unmarried man, the man who has discerned that he is not called to consecrated monastic life, instead finds himself drawn to his vocation as a Benedictine oblate. An oblate is a layman affiliated with a particular monastic community who observes the Rule of Saint Benedict in a way suited to life outside the cloister. In attaching himself to the monastic community, Durtal finds the companionship and spiritual discipline needed to foster his own growth, while living outside the cloister provides him the freedom to foster his aesthetic gifts, not for the pursuit of wealth or pleasure, but for God’s glory and the proclamation of the Gospel.

Near the conclusion of L'Oblat, Durtal observes that the Benedictines are the natural home of artists, as they are explicitly mentioned in chapter 57 of the Rule of St. Benedict. The creation of sacred art flows out from the communal prayer of the Office. “Religious art,” Durtal proclaims, “can be revived; and, if Benedictine oblates have a mission, it is to create it anew and bring it to a high level.”

Art, practiced in this Benedictine way, becomes a prayer offered to glorify God. The creative and material demands of creating art, from the intense labor, the need for solitude, silence, and the financial challenges that often come with the artist’s life have a monastic characteristic that is perhaps better suited to a celibate life than family life. By drawing this similarity, Huysmans, in his own life and in that of his fictional avatar, Durtal, shows us “weird Catholics” that there is, in fact, a place in the greater life of the Church even if we are outside the duality of marriage, on one hand, or consecrated life on the other.

Colin O’Brien, OblSB, is a writer, visual artist, and musician living in Hyattsville, Maryland. He is a Benedictine oblate of St. Anselm’s Abbey in Washington, DC and, like Durtal, is both unmarried and has a colorful past.

Also check out our pieces about Huysmans and aspy trads in National Catholic Reporter and Dimes Square Caths in National Catholic Register, and our interview with Tara Isabella Burton.

Please consider signing up for a paid subscription to this page for more riveting content. If you’re new to Cracks in Pomo, check out the About page or read up on our Essentials. Also check out our podcast on Spotify, Apple, and YouTube and follow us on Instagram and Twitter.

MASA tortilla chips by Ancient Crunch is offering our followers 10% off their order with the promo code CRACKSINPOSTMODERNITY. Click here to redeem.

Beautifully written, Colin, and serendipitously (or perhaps preternaturally) timed for publication. Caryll Houselander is smiling!