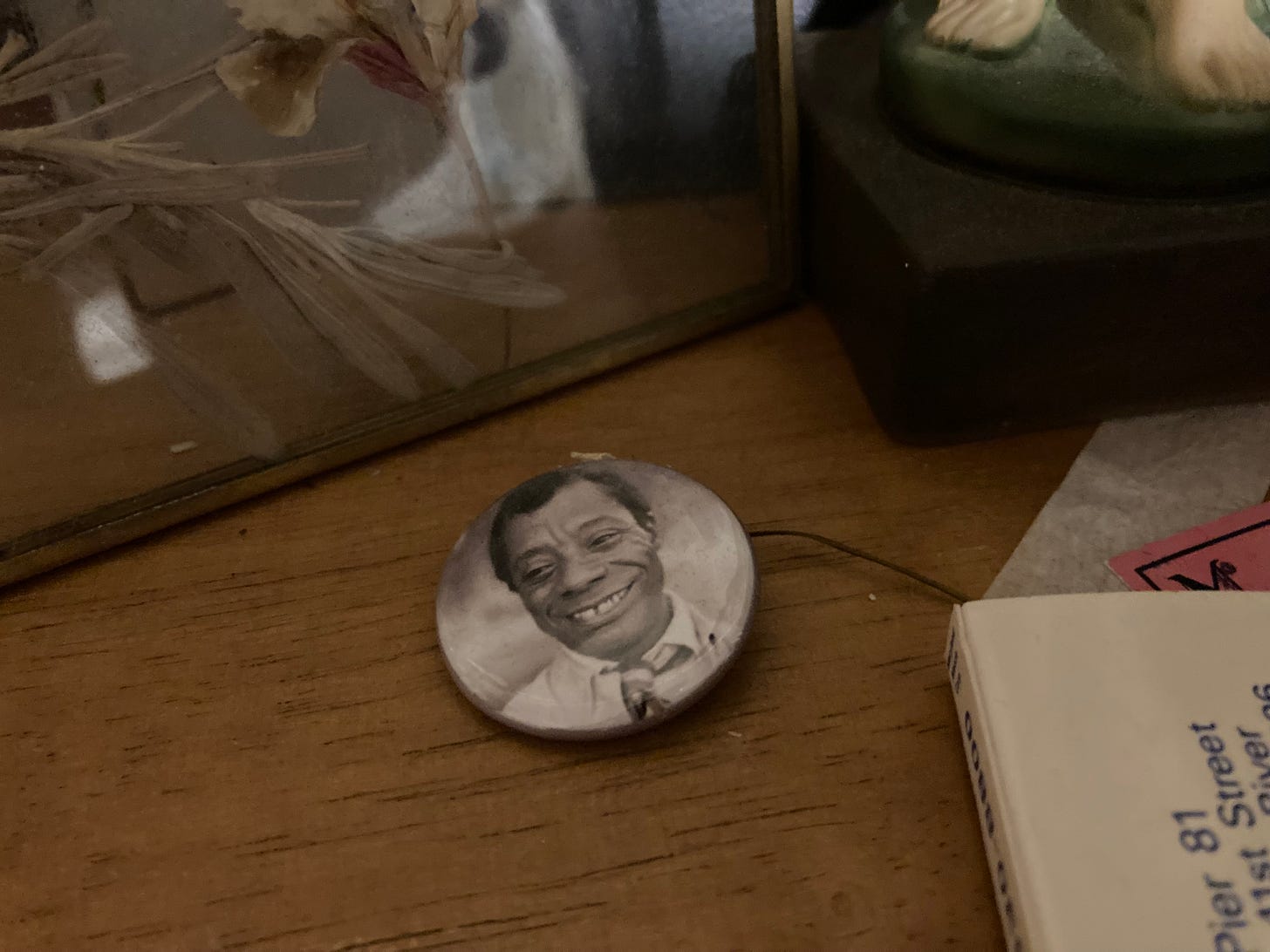

James Baldwin is a genius. His writing has tremendously shaped the way I look at race relations, ethnic identity, and the psychological and existential trajectory of American Culture.

In particular, his essay Nothing Personal (an essential on the Cracks in PoMo Reading List) highlights the way that white Anglos, driven by their “Enlightened” principles, left their native lands for the Americas, left behind their “antiquated” ethnic, spiritual, communal, and moral roots to forge new atomized identities, aspiring to live lives of unfettered independence, of bourgeois comfort, and gaining wealth for its own sake. The result, inevitably, was their losing touch with their own humanity as well as that of others.

The aspirations of Anglo colonists and pioneers drove them to enslave their fellow human beings. Their new disenchanted view of humanity made it easier for them to justify the immorality of their actions. In order to understand and develop respect for POCs, Baldwin insisted that whites need to get in touch with their own humanity—which I would argue would involve recovering their ethnic roots and recovering the communal, “enchanted” worldview of their ancestors that they lost in the process of assimilation (might be worth checking out Chloe Valdary’s “enchanted” version of DEI/Anti-Racist training for this reason).

It’s no secret that Baldwin was conflicted about his homoerotic tendencies. His strict Pentecostal upbringing was the perfect pressure cooker that yielded the archetypal repressed homosexual artistic genius that Baldwin came to be known for. As much as I highly esteem Baldwin, I have strong reservations about Baldwin’s puritanical moralistic tendencies.

Like many other internally conflicted queer artists, Baldwin exhibited a proclivity for Dionysian decadence. Queer men are iconoclasts. Symbolically, the homoerotic impulse puts one in conflict with nature, with social convention…which provides the impetus, claims Camille Paglia, for homosexual men’s turn toward creating art and cultural contributions. The tension between the impulse to engage in unnatural, “abominable” acts and to renounce one’s fleshly desires in the name of some supernatural ideal gives queer men an ability to see through “respectable” moral norms and to see into the true nature of good and evil—thus queer men’s knack for truth telling and “reading” people.

Morality is not what society tells us it is…its origins lie not in social convention nor in our autonomous wills, but in a higher, transcendent form of Beauty. Thus the paradoxical combination of decadent, aestheticist debauchery and “anti-moralistic” moral witnessing. Such figures, likes Oscar Wilde and Andy Warhol, flourished in predominately Catholic cultures—whose more ontologically nuanced awareness of aesthetics and morality made it easier for queer men’s paradoxical sensibilities to flourish. The decadent aesthete is an inverted prophet. He points to truth by living a lie, points to nature by reveling in artifice. His way to truth is through a mirror or a backdoor.

Within the Protestant paradigm, everyone attempts to play John the Baptist, with the inevitable result that no one becomes a John the Baptist. Baldwin excuses himself from striving toward the Good in his personal affairs by calling out all of those who do not strive earnestly enough toward the Good. Baldwin’s moralistic harping and stunted decadent sensibility renders him both a bad prophet and bad aesthete.

Decadent prophets like Wilde are the counterpart to the archetypical ascetic prophet like John the Baptist. Within the Catholic moral paradigm, there is space for both, as they complement each other and place different accents on the same essential Truth: that no one is good but God alone. The former does this by living in sin while acknowledging their sinning is sinful, thus attempting to wake up others to the truth of the way they live, while the latter does this by acknowledging they are a sinner and striving toward God who is the ultimate source of Goodness, and encourage others to do the same.

Baldwin’s ontologically flat, aesthetically unimaginative, and morally harsh Protestant upbringing made it rather difficult for him to weave together his decadent and moralizing poles. He seemed to be perpetually stuck in a frenetic state of cognitive dissonance, with each pole constantly trying to dominate the other. Unlike Wilde, who based his moral worldview on the premise of his own immorality (rather then hypocritically brushing it under the rug), Baldwin was quick—perhaps emulating preachers from his childhood—to point the finger and cut deeply into the moral flaws of others, while rarely acknowledging his own moral incoherence. While he had no qualms with reading well-meaning white liberals, he never really owned up to his numerous destructive and emotionally manipulative affairs with men who were much younger than him.

The Protestant affinity for prophetic witnessing is often cut short when so-called prophets present themselves as “saved,” as distinct from the rest of the flock, rather than a fellow sinner. Baldwin’s moralism stifled his decadent sensibility and set the precedent for current-day moralistic proponents of social justice who know how to point the finger at everyone but themselves. Baldwin is proof of the slippery slope from ontologically flat versions of Protestantism to the outright materialism and puritanism of poststructuralist critical theory.

Check out more of my writing on Baldwin:

Reading James Baldwin can help heal the wounds of racial division-America Magazine, 6/3/20

James Baldwin, blindness, and Hagia Sophia-National Catholic Reporter, 9/16/20

Looking at America’s Wounds Through James Baldwin’s Eyes-Faithfully Magazine, 11/3/20

$upport CracksInPomo by choosing a paid subscription of this page, or by offering a donation through Anchor. Check out my podcast on Anchor and YouTube and follow me on Instagram and Twitter.