Monk Without a God

On Matthew Binder’s Pure Cosmos Club

Order a copy of the zine vol. ii while they’re still available and attend our launch party on 7/11.

Listen to Matthew Binder’s appearance on the pod and at the Holy Lit! event, and read an except from his novel. You can purchase it here.

A small fire flickers on a sandy shore in the Hamptons just after dusk. One silent servant, newly arrived from Latin America, tends it while her counterpart roasts vegan sausages on skewers. They don’t dare whisper in Spanish about their plutocratic bosses: An international assembly of financiers, industrialists, OxBridge dons and young models, each speaks an untold number of languages. Up the beach stumbles an impoverished New York artist, our narrator, Paul, naked, crusted with lake grit, having narrowly escaped drowning moments before, when, by bare luck, a current beached him. No one had noticed when he submerged, and no one notices as, now, he finds his swimming trunks where he had left them rolled on the sand and sits by the fire.

“The Pure Cosmos Club’s moral imperative is not guided by a political vision but a divine one. We have a duty to transcend the drudgery of our daily lives by tapping into the universal mind, the oneness of all things. Come and grow with us—emanate your energy and power!” This from James, “perhaps the most enigmatic man in the world.” Raised to be a missionary, James became a computer programmer, athlete, and Yale debate champion, all before ghostwriting Barack Obama’s Nobel acceptance speech as a sophomore. After college, he disappeared into the mountains of Tibet and returned years later to start the Pure Cosmos Club, offering spiritual ascension in exchange for astronomical donations.

The Club, which charitably lends its name to Matthew Binder’s third novel (surely for a tax write-off), is a forensic caricaturist’s composite sketch of Heaven’s Gate, Jonestown, and Scientology, as James, its leader, looks like the same artist’s mash-up of Jones, Hubbard, and an archetypal Ivy League wunderkind. So pre-publication press releases and reviews rightly called Binder’s novel a “satire of the New York City art scene and of new age cults of personality” (Michael T. Fournier of Razorcake Magazine) and a “picaresque with a satirical eye trained on spiritual and aesthetic hucksterism” (Sam Lipsyte) and a “novel of high comedy as absurd as our present-day reality” (Paula Bomer).

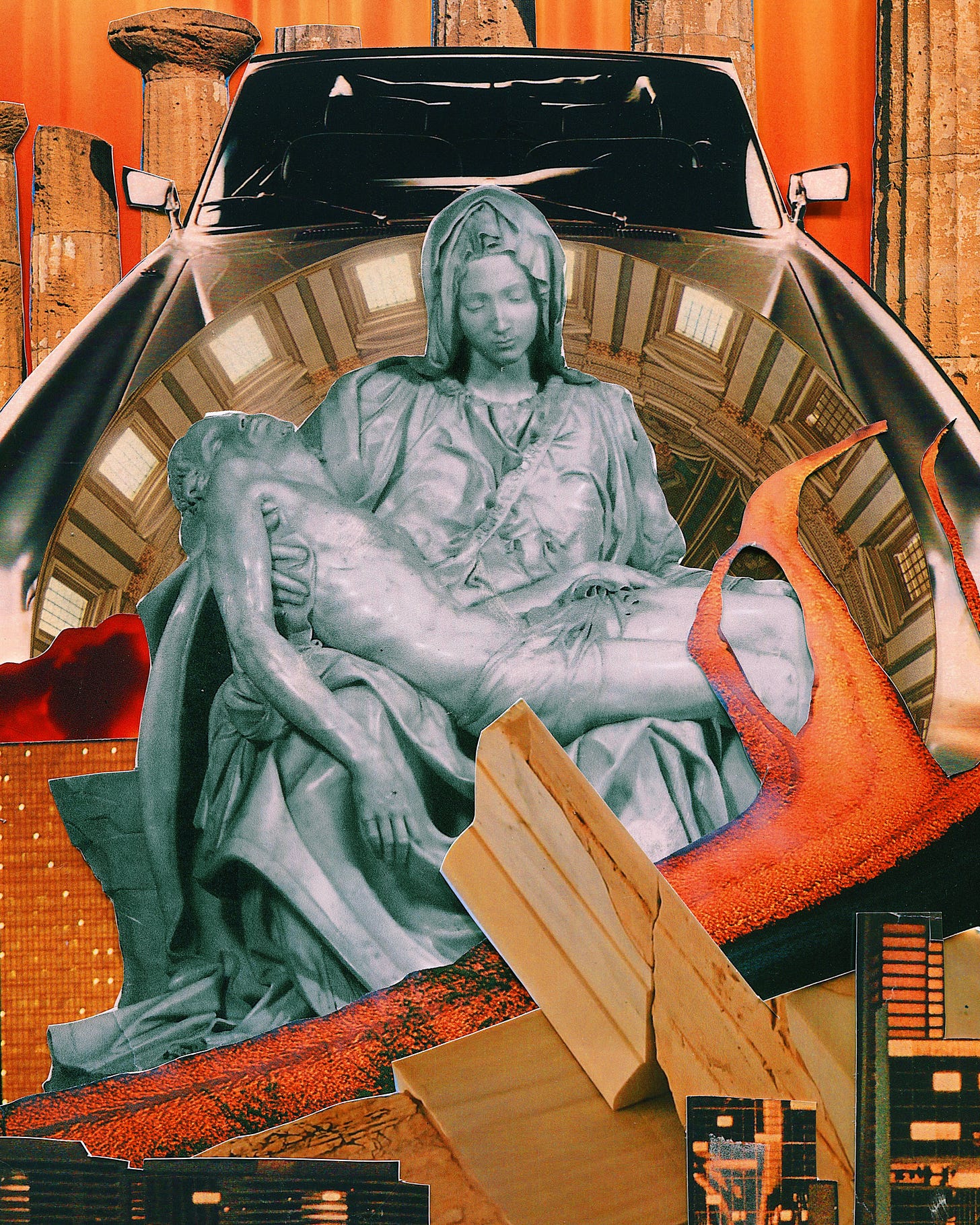

Sure. Without question Binder writes into the satiric tradition—but he also strips that tradition bare by landing his punches so squarely on the nose that the bone, nerves, and finally soul start to show. His blunt ribbing of the New York art world and elite spiritualist cults is just the skin. Beneath, Binder has built in his protagonist-narrator Paul the image of a 21st-century monk without a god, devoted to contemporary paranoia the way medieval monks devoted themselves to Mary. What results is a satire, yes, but also a dissection of satire from word-level outward.

Binder explains to D. Foy in an interview for Lithub, “Many readers and critics will call this book satire, but I’m not sure that’s exactly right. I’m not using humor or irony to criticize anyone. I’m showing my characters as they are, and it happens to be funny.”

Leaving aside that much of Binder’s interview reads like a character study of his novel’s narrator, Paul, it’s clear that his book is satire, not only in the sense he questions, but in various other senses that stretch back through the word’s history.

The genre’s name comes from Latin “satura,” which denoted fullness and variety, originally used to describe a tray of mixed food called a “lanx satura,” similar to the modern charcuterie board. The Romans later used “satura” for a strict type of comic poem, and punning confusion with the Greek “satyr” embedded into the word’s history a connection to Dionysus, god of drunkenness and gleeful disorder. It doesn’t matter that this link arose from some ancient offhand pun. It stuck for so many centuries that it remains baked into the word as much as any supposedly legitimate etymology.

Binder structures his book according to the original etymology, that charcuterie tray, that smorgasbord. A chapter may consist of a single vignette, seemingly divorced from the events that surround it, or a page-long sidebar in which Paul narrates nonlinear places and times with no limits but the speed of his implied pen and the ascetic extremity of his paranoia. But the novel doesn’t become a postmodern fragment-festival. Its consistent tone and careful plotting link its carnival of scenes with tight, joking nonchalance that often feels like alchemy. But neither does it allow itself a straight plot’s weight.

Novelist Clancy Martin calls Binder the “American Murakami.” Forever Magazine describes his writing as “like Houellebecq but good-natured.” Neither quite fits. Faithful to the confused etymology of its genre, Pure Cosmos Club floats away from itself with the Dionysiac lightness of a cartoon character inflated by champagne bubbles. Its closest literary companion is Gaius Petronius, supposed author of the 1st-century AD picaresque Satyricon. Except that Binder relies more on the gods, be they dead or not.

Just before the novel’s midpoint, we find protagonist-narrator Paul trying to sell a crucifix sculpted from broken smartphones. Unemployed, he works in studio space generously allotted him by Danny, arch-degenerate son of a fracking magnate. Paul’s sculpture has won a spot in a small New York gallery show. Danny has sold a handbag sewn from roadkill catskin to a Paris fashion house for some unthinkable sum, and the frenchies want more. He uses his dad’s money to hire a team of foreign seamstresses and tasks Paul himself with gathering dead cats.

The conventionally satirical stratum of Binder’s novel is so on-the-nose as to attain no depth, all surface. No analysis, all sensibility. Fever dream or Dionysiac sketch of a resentful outsider-artist. Its ridicule is blunt, and the critique it implies is so audaciously passé that it screams the presence of another level. That level gropes for itself in the space left by the novel’s most conspicuous absence: Outsider-artist though he be, Paul harbors no resentment and does not want to raise his station.

Offered money by a couple he’s sketched at Penn Station, he refuses. As the wowed wife raises her bid, Paul flees. Before he joins the Pure Cosmos Club, its sinister leader, James, expresses awed admiration for one of his paintings. Paul offers it as a gift. Later James sells it for fifteen thousand dollars. Paul doesn’t ask for a cent. Danny, returning to the studio to deliver news about the success of his roadkill catskin bags, stares at the sculpture in awe before accidentally drenching it in gasoline, upon which a stray spark destroys the piece. Paul refuses to ask Danny for payment, musing that “after staking out such a contrarian position against Danny's artistic judgment, it would be impossible to argue for reparations without making myself look like a hypocrite and an imbecile.” On the verge of eviction, Paul resuscitates his landlord, upon which the grateful man offers to let him stay in his apartment rent-free for as long as he needs. He moves out the same night to sleep on a pile of junk in Danny’s studio.

Binder’s construction of Paul as character and as narrator is as meticulous as a solid voice-novel demands. He leaves no way to explain away Paul’s poverty as a result of his anxious timidity or bad luck or social forces. The artist is a monk. He is committed to the mortification of flesh which his vocation necessitates. “Paul doesn’t believe in a universal account of truth,” Binder explains in Lithub. “He refuses even to obey the simple rules of arithmetic because they limit what is possible.” And so he devotes himself to paranoia, a pure cosmic drunkenness in which everything emits signals in a language he cannot understand, and his every movement is a layered faux pas.

When he’s not busy with wry explanations of his monkish tendencies as relics of childhood trauma—he likes to sleep on hard garret floors because he cried so much as a baby that his callous father put his crib in the attic—Paul occasionally drops a cryptic explanation of his godless asceticism. Most telling: “I feel torn between two beings, each as rare and unattainable as the other.” This line points to a superstructure à clef, clarified by Paul’s later question, “Why does a man have to stick to an idea just because he thought it before?”

Binder says in Lithub that Paul loves animals because they show him a graspable order he can’t find in relationships with humans, but Paul clings to animals and natural spaces precisely because their multitudes of voices echo the cacophony of uncertainties in his own head. In the animist roller-derby of souls, he fits in. But among people, he is confronted by certainties he can’t comprehend and which force him inward as self-diagnosis and as self-flagellation.

“It’s best not to be so introspective,” Paul tells a stranger who has picked him up on the side of a highway. “No one ever likes what they find.”

Paul follows the instructions in advertisements meticulously. Trembling he describes various strangers and friends as “savior” or “godly,” but he reveals no religious affiliation. He frets for decades over whether any god answered his childhood prayers. “One must take accountability for their own misfortunes,” he says, pages before he contradicts himself, in full Calvinist style, “My fortune was written in the celestial ledgers.”

He is not only a monk without a god, but a monk who cannot believe in his god because to be in the elect of the paranoid requires exclusion from that same elect. Paul is a devotee locked out of a heaven he knows can’t exist. For such a monk, in his own words, “Anything but a full embrace of detachment rings false. It’s time to carry the torch into the dark.”

In the textually implied mouth of the ascetic Paul, the surface-levels of the novel’s satire read as ridicule of themselves. The subversive resentment such satire would normally imply fades away into…what?

Paul denies every advantage given to him out of unexplained and often cringe-inducing desperation to find the lacking god to whom he’s devoted himself in absentia.

And he goes nowhere. He begins, detours, rests, begins anew, and ends at that divine question mark. That’s the riddle that makes this book worth re-reading. On the first read, it’s just funny. But the second read reveals Paul’s inscrutable mysticism, his monkhood of inscrutability. His paranoia ascends from plot point to prayer, in the way that anything repeated when the devoted doesn’t grow tired of the repetition becomes prayer.

Which is to say, Pure Cosmos Club demands a reread, and at the very least a read. “The chaos of Paul’s mind,” Binder says in his interview with D. Foy, “does have an internal logic.” That internal logic spans the levels of satire’s viscera, historical and humorous and self-reflecting, from the skin on the nose into its bones, marrows, shifting spirits.

I’ve often told friends that Samuel Beckett’s Watt is funny because it forces you to laugh at yourself for reading it. Binder’s Pure Cosmos Club is the opposite. Once you have occupied Paul’s paranoid eyes, you start to laugh at yourself for thinking you could ever read anything. That type of laughter is a liberation and a horror, and worthwhile for both reasons.