Get a discount on annual subscriptions here!

Happy President’s Day. In the media zeitgeist’s coverage of the changing of the guard from Biden to Trump, few outlets reported that Marcus Garvey was among the people Biden pardoned before leaving office. We thought we’d take this opportunity to remind you of our esteem for Garvey…and to take you through my recent Sunday in Harlem (and the Met).

The Met is doing diversity right

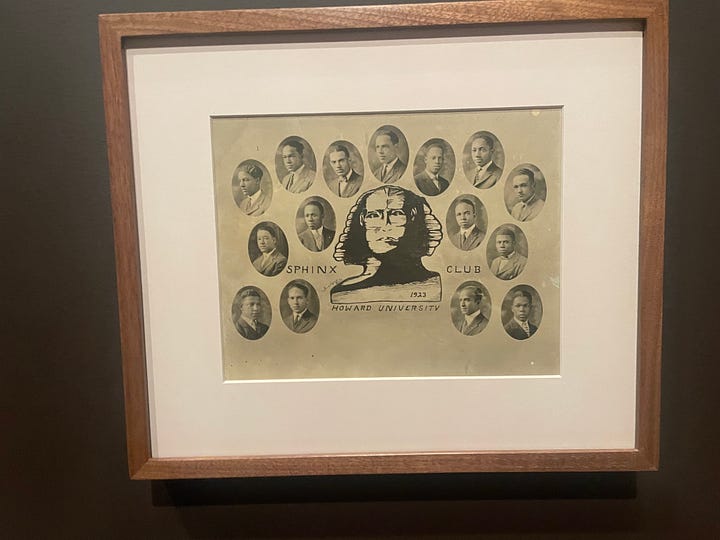

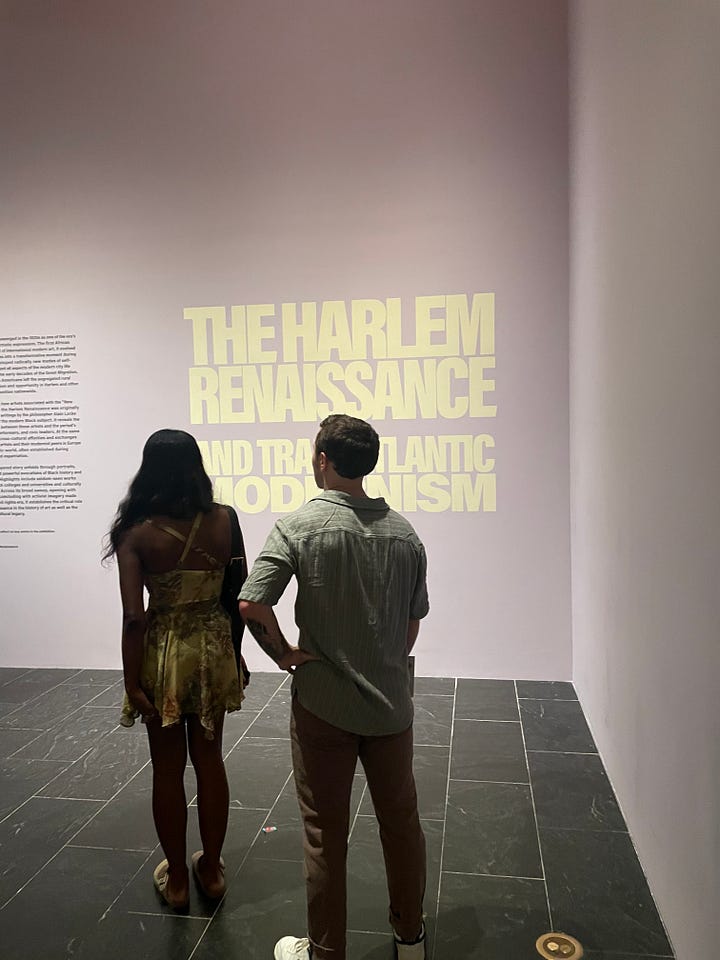

After visiting the Sienese art exhibit (which was fab), my friend and I visited “Flight into Egypt: Black Artists and Ancient Egypt, 1876–Now” which “examines how Black artists and other cultural figures from the 19th century to the Harlem Renaissance to the Black Arts Movement of the 1960s and 1970s to the present day have engaged with ancient Egypt through visual art, sculpture, literature, music, scholarship, religion, politics, and performance.”

The curation was dazzling —featuring historical and pop cultural artifacts inspired by the Pan-Africanist esteem for Ancient Egypt. But as I tweeted, the curation was devoid of ideological identitarian fodder. I applaud the Met for including more “diverse” content which actually has real substance—it feels like they display them because they think they are inherently interesting, and not because they are trying to check off a box. Further, they allow their Afrocentric exhibits to speak for themselves rather than preaching at us (like they do at the Brooklyn Museum).

As I wrote in

’s Substack about last summer’s Harlem Renaissance exhibit:The captions featured alongside the pieces were refreshingly objective and substantive, unlike those found at other NYC museums (The Whitney, Brooklyn Museum) where the curation tends to regurgitate the identitarian script to the point of sounding algorithmically-generated. Though not covering over the realities of racial discrimination, the Met’s curators allowed these beautiful pieces to speak for themselves rather than presuming to tell spectators the “correct” take-aways.

The case was similar at the previous summer’s exhibit on Juan De Pareja and Arturo Schomburg—a real masterpiece of an exhibit, which I wrote about for The American Spectator.

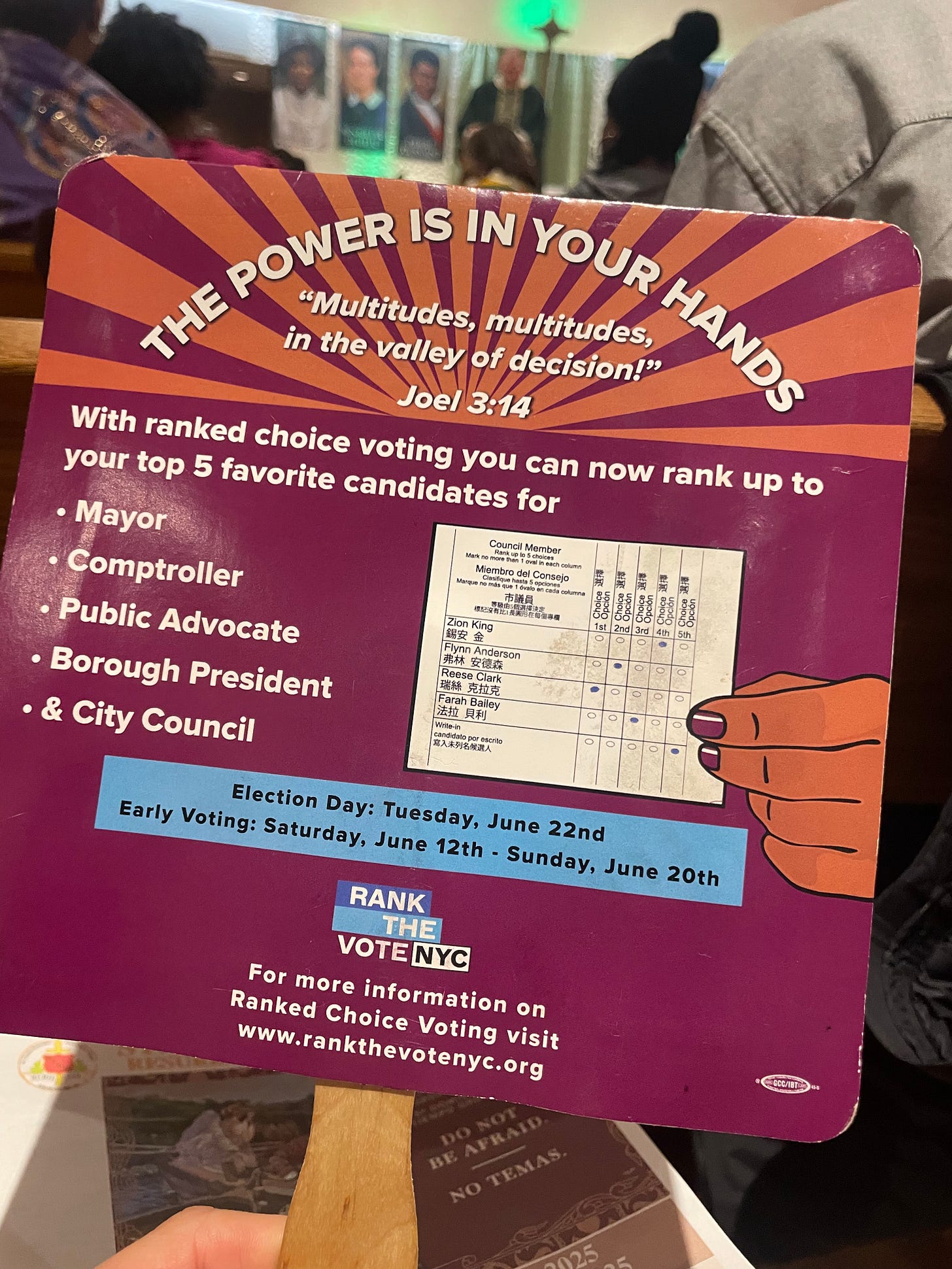

Gospel Mass at St. Charles Borromeo

Later, we went uptown for Mass at the St. Charles Borromeo, a historically black Catholic parish, that features a Gospel choir. The Mass was incredible, the community extremely welcoming—taking much pride in welcoming visitors to their parish. The entrance was draped in banners of the six black Catholics who are up for canonization—which hopefully Francis will expedite (along with Dorothy Day, Giussani, and Carmen Hernandez).

Every part of the Mass was extremely intentional—the ushers, the music, the homily, the prayers. The liturgy gave me hope for the future of the Novus Ordo Mass (which I rarely if ever look forward to attending). It perfectly embodied the ideals of Vatican 2’s liturgical reforms: spirited lay participation and integration of the (living) tradition particular to the given community. It was an hour and 45 minutes of jubilant worship of God…I rarely walk out of a church with tears in my eyes and joy in my heart (except at a non-assimilated Divine Liturgy or at the Tridentine Passion Service on Good Friday).

Also there was an insane amount of Italian tourists there, whom the priest took a moment to shout out after his homily (and to whom the ushers made it clear that this was a liturgical moment and not a tourist attraction, as they kindly asked them to stop recording the choir on their phones).

In 1979, Pope John Paul II visited several black Catholic parishes around the US, including Charles Borromeo, where he lauded them for having “nurtured here the cultural, social and religious roots of black people…for half a century.” The fact that he gave visibility to black American Catholics is a big deal given the fact that the American Church horribly neglected them and their communities. Whenever I tell people I visited a black Catholic Church, they are shocked that black American (non African or Caribbean) Catholic communities exist. This is why you need to read Fr. Cyprian Davis’s masterpiece of a book The History of Black Catholics.

The whole experience confirmed my conviction that one of the greatest threats against black communities is their being cut off from their rich historical, spiritual, and cultural legacy—which is one of the greatest sources of empowerment, both existentially and sociologically. When teaching in a predominantly black institution, I could see a big difference between the kids who knew their history, were close to their elders, and were tied to a church or other communal organizations, and those who didn’t. The loss of one’s roots is one of the worst forms of suffering.

Walking down to Malcolm X

After that, we walked down to 125th and Malcolm X, passing by the Arturo Schomburg1 branch of the NYPL (again, read about him in my review of the Met’s fabulous exhibit on him), the Five Percent Nation temple (one of the most fascinating offshoots of the Nation of Islam—Erykah Badu was one of them) and the Malcolm X mosque, and made our way into Sylvia’s for some soul food, accompanied by more Gospel music from a live singer. My friend was amazed by how much the staff—both the young and old ones—took such pride in working in a historic institution which makes up a crucial part of the fabric of the neighborhood. It’s rare to see restaurant workers who are happy—and whose happiness is not the product of customer service indoctrination.

While eating our chicken and waffles with mac and cheese, candied yams, collared greens and sweet tea, my friend and I were shocked—once again—by how many Italians were there. We were told that on top of being drawn to the cheap hotels in Harlem, Italians seem to have some kind of fascination with black American culture. And apparently the feeling is mutual—given the amount of black women who are into Italian men (it’s a thing, I swear).

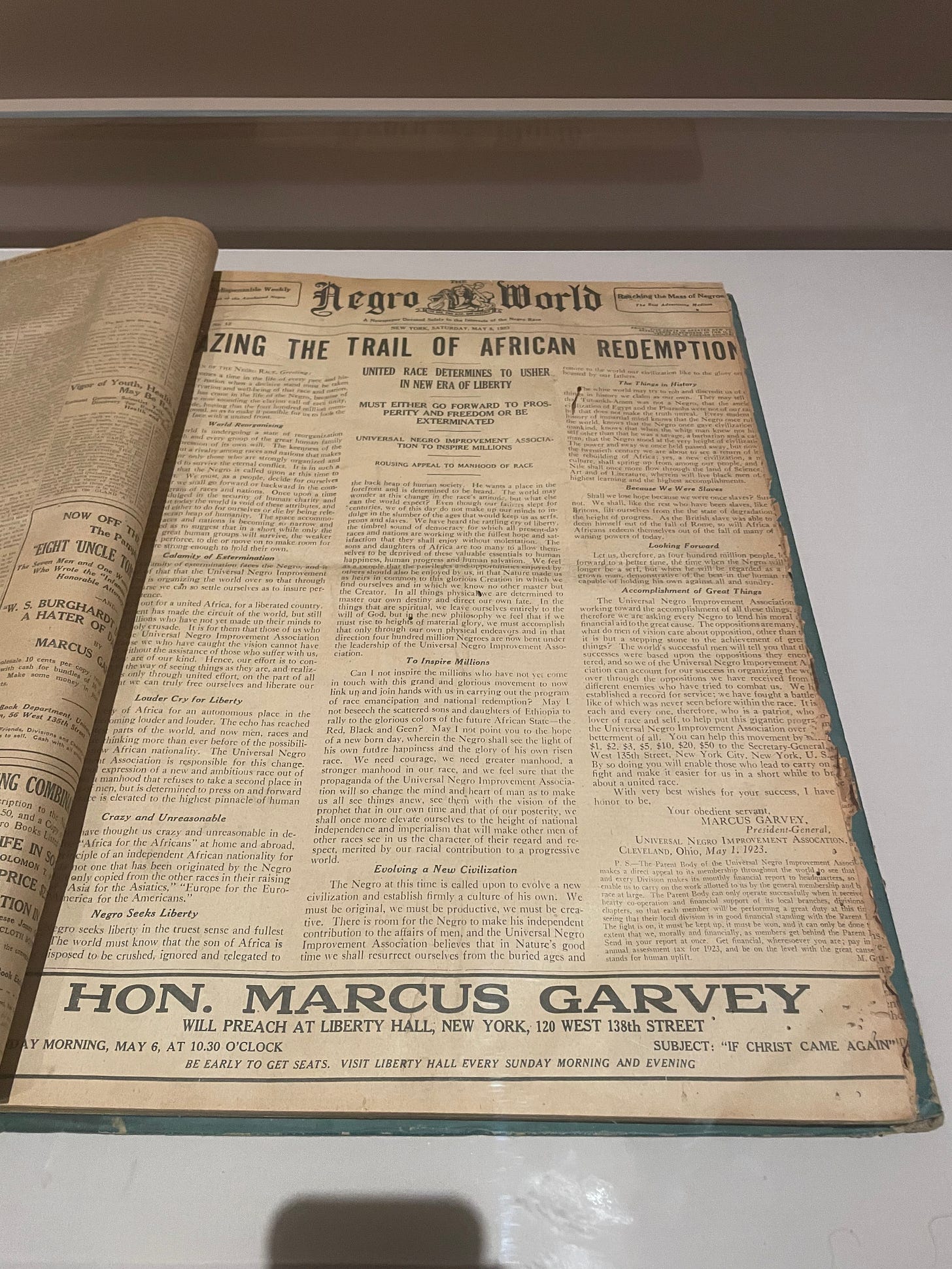

On the way back up, we passed by Marcus Garvey Park (where Brother West had his rally last spring) and St. Mark’s Catholic parish where Garvey once gave a speech in 1916. When my friend admitted that he knew nothing about him, I took the opportunity to babble like an autist about the wonders of Garvey—who was featured in two of the aforementioned Met exhibits.

I took it as a divine sign when I found out that Biden pardoned Garvey the very next day.

Garvey was not colorblind

So why are we so into Garvey? Some people say it’s because I am a f*scist—to which I won’t even give the dignity of a response. In reality, my fascination with Garvey began when I found out he was Catholic…and was deepened after Beyonce’s Black is King sparked my curiosity in Pan-Africanism. As I wrote in Catholic World Report:

Several of the film’s spoken interludes and its general aesthetic quality draw heavily on Pan-Africanist philosophy. Popularized by figures such as Marcus Garvey and Kwame Nkrumah in the first half of the 20th century, Pan-Africanism aimed to counter the effects of slavery and colonialism, unite descendants of enslaved Africans in the name of establishing bonds of solidarity, and celebrate their shared heritage.

Eventually, I wrote this essay for Sublation, highlighting how Garvey’s Catholic faith made him immune to the “colorblind” approach that MLK’s ilk went on to promote, emphasizing the beauty and givenness of black heritage. Here’s an excerpt:

Though significant scholarship has been published about the religious dimensions of Marcus Garvey’s legacy, the faith of the godfather of Black nationalism is unfortunately forgotten or blatantly ignored by many. Born in Jamaica in 1887, Garvey’s Pan-Africanist movement was premised on affirming and retracing the roots of descendants of the African diaspora, spurred by the recognition that a rootless person can only feebly attempt to claim his or her dignity. In contrast to most social movements today, Pan-Africanism offered a thorough, comprehensive vision – encompassing the metaphysical and material, the aesthetic and political.

Disillusioned with the limited Protestant theological imaginary of the Methodist tradition with which he was raised, Garvey converted to Roman Catholicism, while also maintaining a close relationship with Ethiopian Orthodox Christianity. Rastafarian theology borrows many ideas from Garvey – and hails him as a John the Baptist-type prophet for “predicting” the rise of Haile Selassie as emperor of Ethiopia. Yet Garvey “scorned” Rastafarianism, and dismissed the claim that Selassie was the second coming of Christ as “blasphemy.”

His fidelity to Catholic doctrine was loose, as he often spoke of forging a new form of “Black Christianity” – yet expressed that he wanted it to be as close as possible to Catholicism. He affirmed that God transcended race, but that “it is human to see everything through one’s own spectacles, and since the white people have seen their God through white spectacles, we have only now started out (late though it be) to see our God through our own spectacles.” Thus his insistence on black people praying to images of Black Jesuses and Marys, perhaps a reflection of the stronger emphasis on particularity found in Catholicism.

Essential to his ideology was the idea of blackness as a gift from God to be celebrated and enjoyed, constituting a rich legacy upon which Blacks should draw inspiration for their endeavors. Without such an awareness of blackness as gift, it would be impossible to restore the Black man’s sense of dignity and worth. Upon his visit to Garvey’s grave in 1965, Martin Luther King shared his esteem for “the first man of color to lead and develop a mass movement. He was the first man to give millions of Negroes a sense of dignity and destiny on a mass scale and level. And he was the first man to make the Negro feel that he was somebody.”

…

Unlike today’s libertarian bootstrappers, Garvey was hardly an individualist. His self-determinist and anti-big government musings were tempered by his communitarian vision – centering the people, the community as the locus of agency. This is where Garvey and the movements he inspired most echo Christianity. Central to the Catholic Church’s social tradition are the complementary principles of subsidiarity – that neither the state nor any larger society should substitute itself for the initiative and responsibility of individuals and intermediary bodies, and solidarity – a sincere commitment to the Common Good. Ideally, the two principles temper each other, with subsidiarity protecting smaller entities from being overpowered by larger, distant ones, and solidarity ordering the smaller to the large, the particular toward the universal, aiming to foster loving unity among all peoples, reconciling differences and forgiving offenses.

Please do read the whole thing—it was one of the pieces I most enjoyed writing last year.

This is in part why I loved those Met exhibits—and their portrayals of Garvey—so much: They portrayed blackness as an living tradition, a dynamic cultural legacy, rather than a mere identity.

Lasch on MLK

Lastly, I came across this bit about MLK in a wonderful biography of Christopher Lasch…noting his shift away from his original populist-adjacent position:

The one great moment of populist triumph Lasch saw in the twentieth century was the civil rights movement. He described Martin Luther King Jr. as populist in orientation and ethos, a shocking narrative turn that showed both the power of Lasch's historical framework but also its limits. King, due to his upbringing in the South as the child of a conservative Baptist minister, had imbibed both "prophetic religion" and more generally populist sensibilities, and his education in the Northeast, where he encountered above all the work of Reinhold Niebuhr, had attuned him to the deeper intellectual (and less orthodox) dimensions of the faith.

…

But it was not just King Lasch was applauding; King's followers were his true heroes. Their virtuous embrace of what Niebuhr had called "the spiritual discipline against resentment" was the starkest manifestation of the sensibility and stance Lasch had throughout the book been propounding. "Their experience in the South gave little support to a belief in progress," Lasch underscored, "yet they seemed to have unlimited supplies of hope." The movement had depended on "spiritual resources — courage, tenacity, forgiveness, and hope" - that had been nurtured in their own communities.

"Social theories that equate moral enlightenment with cosmopolitanism and secularization cannot begin to account for these things," he averred. The failure of the civil rights movement in the North stemmed precisely from its inability to build on the embodied, local, rooted vitality that sprang from the Southern black communities, and King's own faltering effectiveness as a leader in his last years occurred as he both departed from his own place in the south and allowed his earlier ethical ideals, centered on charity and nonviolent confrontation, to be weakened.

Lasch's criticism of King's late turn away from this radical, Christian, localist vision and toward a more standard form of democratic socialism revealed the heart of Lasch's own post-socialist political economy: King "did not explain how a guaranteed income would restore self-respect or the pride of workmanship," Lasch noted. These for him needed to be at the base of any decent society; they were certainly the fruit of any decent economy. "Participation," not "distribution," he emphasized, is "the test of democracy."

Anyway, take a trip to Harlem—and to the Egypt exhibit at the Met before it closes this summer.

Schomburg (after whom the Harlem branch of the New York Public Library is named) was a writer, historian, and activist born in Puerto Rico in 1874 to parents of Black and German ancestry. When studying in elementary school in Puerto Rico, Schomburg “asked a teacher when would they get to learn about Black history? And the teacher told him there was no such thing. That Black people didn’t have a history.”

This answer spurred him to embark on a lifelong journey of uncovering the history of his roots, eventually going on to co-found the Negro Society for Social Research. While visiting Seville, Spain, he learned about the extensive history of Black enclaves that have persisted in the city, as well as others in the south of Spain, among whom were figures like de Pareja, Leo Africanus, Sebastián Gómez, and Diego Ortiz de Zúñiga, who contributed works of art, theology, and history.

For Schomburg, discovering the existence of such communities and the works they created shaped his sense of his own identity, filling him with pride and dignity (which he vividly describes in his essay “In Quest of Juan de Pareja”). Thus his sense of mission when returning to the Americas was to not only create more educational and economic opportunities for descendants of the diaspora but also forge meaningful communities that were spiritually nourishing and connected people to their rich histories — which had been deprived of them by the slave trade and racism.