Purity Culture Is (Unfortunately) Here to Stay: A Twist on Paglian Archetyping

by guest contributor Bridget Ruffing

I grew up in the intersection of deracinated evangelical Protestantism and 90s-haunted, Lifeteen Catholicism known as Central Maine. Ask a woman what it was like to grow up religious in the Northeast counterpart to the Unchurched Belt and they will either give a halting, qualified-then-requalified answer, or they’ll just tell you it sucked. And, odds are, they’ll tell you about the purity culture that pervaded their minds, their closets, their relationships, and their youth retreats.

Being homeschooled, I had to get creative when making friends. I joined public school sports teams, and attended Bible studies, lock-ins, and Superbowl parties hosted by the local Baptist church. I performed in Shakespeare plays directed by the socialist-turned-Anglican-in-disguise pastor of another Baptist church. I looked for love among the Calvinist, evangelical, mega-church crowd and at my extremely tiny Catholic college. There, I learned the terms ‘trad’ and ‘SSPX-er,’ and was judged for preferring the Novus Ordo.

I ran the ecumenical gamut and, as I grew older, the discourse around purity morphed from general warnings like ‘boys are blue and girls are red, please don’t make purple’ to claims that women shouldn’t wear pants and that dressing to seduce your husband is sinful. I sat through countless women’s talks, read numerous books on purity, and have seen too many adult women crying over being dress-coded in public. The people changed, the churches changed, but the discussion always circled back to the same problem: how women must dress to be considered ‘pure’, i.e., virtuous and trustworthy.

I wrestled with this question for the better part of twenty five years and never found a satisfactory answer. Then I read Camille Paglia’s Sexual Personae and realized that the question is not one to be answered–it concerns a problem that will never be solved, that will exist as long as women exist.

In Sexual Personae, Paglia explores various archetypes and their sexual, sociological and psychological significance. These archetypes break down along the binary of sky-cult and earth-cult. Man, with his externality of penis, politics, and violence, belongs to the sky-cult and its worship of order, justice, and empire. On the side of earth-cult stands woman with her internality of womb and blood, ritual and unpredictable flux, exemplar of terrifying, enchanting, chthonian nature.

The “femme fatale” archetype, more than the others, encapsulates the aspects of woman that man fears most. The seductive and utterly narcissistic woman, she is nature and sex turned against him, she is the disintegration of his personality and autonomy. Femme fatale characters dominate the film noir canon and today worshipers of the ‘dark feminine’ take her as their idol. The femme fatale entices man with her mystery and wildness. She brings him into her inner chamber where he surrenders himself to the overwhelm of orgasm. Sex renders man briefly vulnerable and gives woman the upper hand. The femme fatale takes full advantage of this situation, manipulating her lover and claiming his time, his attention, his life.

The “beautiful boy” archetype, conversely, represents man free from woman and therefore free of all that terrifies and controls him: namely sex, stagnation and death. Eternally young, lithe, and well-defined, the beautiful boy is Michalangelo’s David, Bernini’s St. Sebastian, Wilde’s Dorian Gray. Paglia writes, “Male homosexuality may be the most valorous of attempts to evade the femme fatale and to defeat nature,” hence his prominent and enduring position in Western Art. The beautiful boy is the ideal partner for the devotee of the sky-cult, just the kind of boy that Plato would take as a part-time lover, full-time student. Smooth and small like a woman but unburdened by the horrors of the womb, he is the terrified man’s safe haven.

Valorous as this attempt “to evade the femme fatale and to defeat nature” may be, man cannot get away so easily. Camille notes: “The danger of the homme fatal, as embodied in today’s boyish male hustler, is that he will leave, disappearing to other loves, other lands. He is a rambler, a cowboy, and sailor. But the danger of the femme fatale is that she will stay, still, placid, and paralyzing.”

If a man’s power is in his vision, determination, and range of motion, a woman’s is in her ability to remain, to saturate, to bi-locate. No matter where man runs, he cannot escape woman, who brings him into the world without his consent, who entices him into herself against his better judgment, who binds him to a home and a family. Woman’s patient nature is a double-edged sword: one wrong move is all it takes to transform Penelope into Clytemnestra.

Paglia posits that every man has a primal, Freudian fear of woman’s cunning and unpredictability. The femme fatale represents everything that threatens progress, order and civilization, and if she can’t be controlled, she must be destroyed for the sake of the social order. This narrative plays out in Greek plays and mythology: Clytemnestra cannot be allowed to live, Medusa must be beheaded.

Love and the continuation of the species, however, demand that women live, have sex, and bear children, so man must make peace with what he fears. A chaste woman, one who is obedient and submits to a standard of conduct, sets man’s heart most at ease. She is Penelope waiting for Odysseus, pulling him home through danger and despair. She is Andromache, staying put behind Troy’s walls, watching over her child, resting her hopes in no other place but Hector’s life. These modest mothers, these virginal wives, are creatures man can take his eyes off while he goes to war. He is spurred on by his love, not bogged down, because he knows she will be there–untarnished and undemanding–when he gets home.

Purity culture rhetoric is one iteration of man’s attempts to control women. A woman is never simply one thing: she is mother and wife and girl and thinker and concubine and killer all at once. Wherever she goes, there, too, goes her sex appeal and the latent femme fatale. Man reckons with the terrifying, multi-faceted existence of woman, therefore, by objectifying it, making it something ‘other’ that he can cover up, undress, and categorize. Girls who grow up in purity culture are taught, often before they’ve hit puberty, that their virginity and the effect they have on men are their responsibility alone, and that the integrity of their souls is on the line whenever they are in the presence of the other sex. Under this standard, a man can discern immediately by a woman’s actions and dress whether she is impure (dangerous) or pure (safe and trustworthy).

Even outside the context of religion, men reckon with the presence of women by reducing them into objects and placing them in boxes–they just do so without playing the Jesus card. Paglia herself thinks like a man, fixating on archetypes with a kind of academic voyeurism: she reduces human beings to tropes small enough to pick up and spin around, to hold and explore from all angles without the threat of retaliation. Internet aesthetics and (insert here)-core lifestyles proliferate on the Internet. Men seek ‘trad wives’ or ‘goth girls’ or ‘baddie’ types. Women often hop willingly into these boxes, trying to alter their habits, looks, and interests to become ‘that girl’ or ‘a tomato girl’ or a ‘gamer girl.’ But an aesthetic, no matter how niche, is still just an aesthetic, not a fit substitute for personhood.

The cycle of purity debates I have endured is endless precisely because women are allowed to participate in it. If men alone were consulted, I think they would quickly reach a consensus. Each would say, ‘a woman should be modest when I don’t want to have sex, sexy when I do want to have sex. When I have a promotion to earn, a golf tournament to win, a book to publish, women should all wear potato sacks. I can wrap my head around a woman in a potato sack. I can put her away for later and not have to worry that other men will want to unwrap her. When I have earned the promotion and won the tournament, then banish the potato sack, bring on the bustier.’

A healthy woman, however, takes pleasure in being a woman, and that means taking pleasure in being soft, sensual, fertile, insightful, emotional, practical, nurturing, and bitchy when her own body is feeling soft, sensual...or even bitchy. A healthy woman won’t be content with a lifestyle of purity that is defined solely by a man’s inconsistent desires. Is she only pure when her husband does not want to have sex with her? Is purity defined by dress, or attitude? But a woman can’t have the same virginal attitude with her husband as she does with society, can she? Does that make her impure in the bedroom? It’s not possible to be a thinking, autonomous woman and be only a virgin, only a mother, only a wife, only a whore exclusively.

Christian women run themselves ragged trying to be pure all the time, trying to define what that looks like, and it’s impossible, because the basis of purity is arbitrary, not integral to their nature. Any woman who recognizes and respects her own personhood will create friction, either inside of herself or with other men and women, when she takes part in the purity discussion. The argument will go on and on, and both sides will remain unsatisfied with how the others’ conclusions play out in the world.

Purity culture will continue to captivate and frustrate as long as man continues to desire what he fears: women. Recognizing that the game is never going to end, I have decided not to play. After all, I’m no Penelope, and I’d like to avoid becoming a Clytemnestra. So carry on with your debate. As for me, life is short: I’ll wear the bikini.

Bridget Ruffing is a writer, photographer, and Style Coach. You can usually find her reading, creating art, trying new coffee shops, or deep-diving into a certain topic. Lately she's been exploring website design, fountain pens, and psychology. Follow her on Twitter, Instagram, and Substack.

Please consider signing up for a paid subscription to this page for more riveting content. If you’re new to Cracks in Pomo, check out the About page or read up on our Essentials. Also check out our podcast on Spotify, Apple, and YouTube and follow us on Instagram and Twitter.

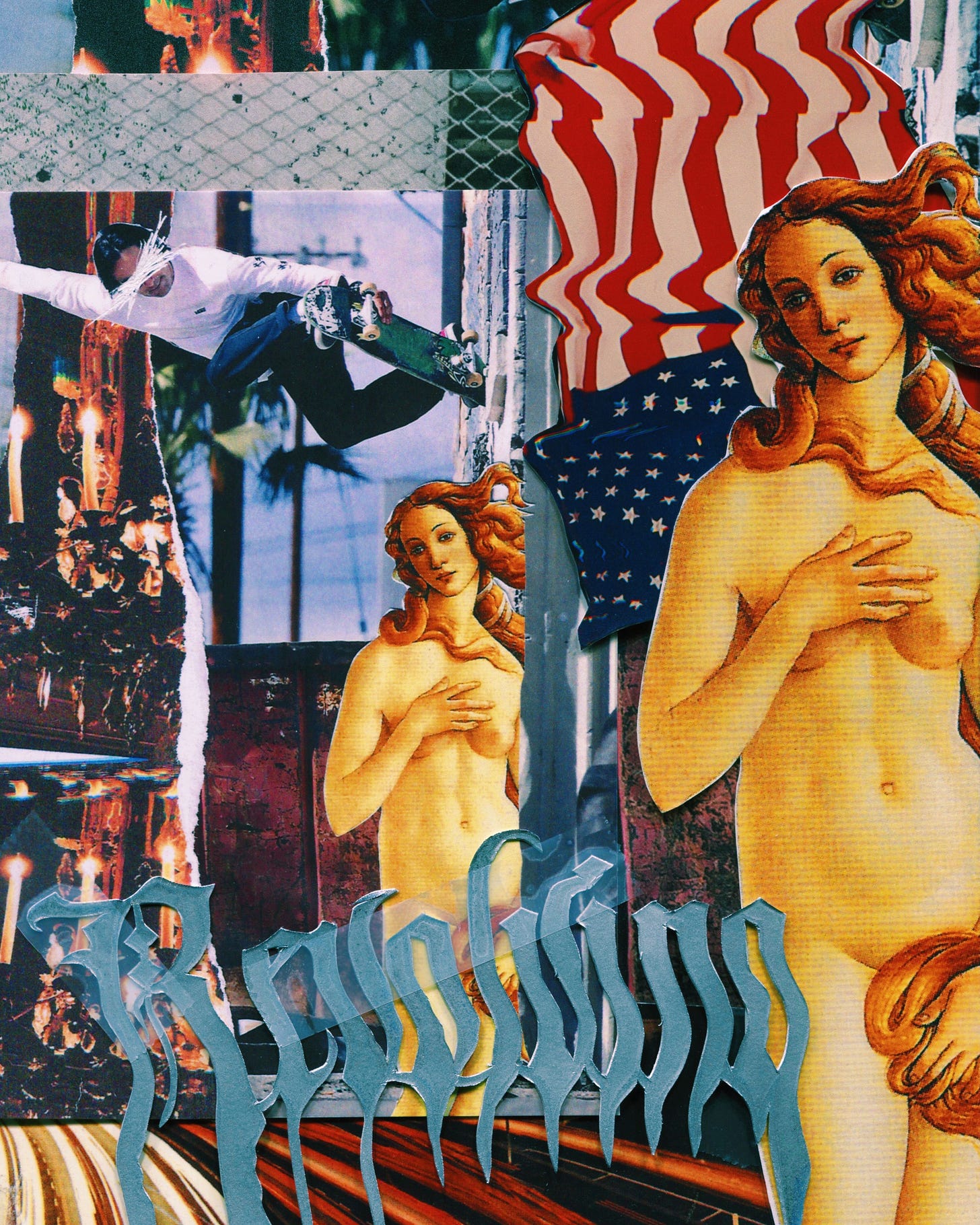

graphics by Patrick Keohane @revolvingstyle

Beautifully written and well constructed! It certainly is a conundrum, and a universal one at that. I have found that all cultures in all times have wrestled to make peace with us; even in our own hearts, we are unsure from age to age how to handle the power of ourselves. From birth to childhood to adulthood to age, the constantly changing nature of our bodies forces us to reimagine ourselves. The Nature of our Nature requires us to explore the truth -

Woman is Woman.

so brilliant, beautifully written bridget. a really interesting refresher on paglian thought, one I'll be coming back and revisiting!