“The specific element of each type of beauty comes from the passions, and just as we each have our particular passions, so we have our own beauty [...] we have only to open our eyes to see and know the heroism of our day.” – Baudelaire.

Ours is essentially a tragic age, so we have resigned to take it tragically. The ruins become us, we yield to devolution, to our petty morbidities. Everywhere we encounter the vulgarity of our resignation; as though there is no longer any life left in anything; and we can but only polish these nuggets of excrement until we face the great leveler herself.

On the surface, it appears as though most are wanting in spirit and thought; secular modernity’s stripping of tradition, bound up in Ezra Pound’s emphasis on making it new, has led us farther into the marshes of delirium and excess. It appears that in the effort of achieving novelty and originality, we deprive ourselves of the appreciation of prior forms.

In simpler words, it has become a matter of surpassing tradition through critique and unmasking, of laying bare a false antagonist, as opposed to broaching the origins of design with recognition. Beauty, as we are told, is already an arbitrary and outdated concept the moment we attempt to take stock of it; it is to be forgotten in its appearance. Is it any wonder, then, that there are those who wish to reclaim the conditions for beauty as an antidote to the new? And moreover, that theirs is an appeal bound up in absolute forms and rejections of the differential?

The conditions are dire. It is everywhere, spread open like a venereal chancre. You need only look and there it is…a purulent sore, a gangrenous gash in the maw of God. The world has ended, and what of it? Have your kill-me pills, become a proselyte for leperous doctrines, join a party and pay your membership dues. What more?

The pervasive mood, at least in part, is one of creative devolution: a narcoleptic culture industry pumping out recycled, formulaic media; devitalised political energies that diagnose the condition yet fail to propose adequate plans of action…those of us who still speak of a left-wing and a right-wing are embittered and dissolute. You no longer wonder, with Guattari, why everybody wants to be a fascist, since in fascism there is a direct appeal to the mythology of progress and Destiny: an antidote to passivity, bound up in the beauty of the mass. Fascism is comparable to the black storm of Blake’s vision: “...coming out of Chaos beyond the stars…through the dark & intricate caves of the Mundane Shell.”

So let’s preemptively call this what it is: an exercise in self-defeat, a practice of aesthetic castratism. We can only be the castrati in a dead Opera.

If we’re still to speak of Left and Right responses to this stagnation, we maintain that there is a general consensus present in either faction of a modern impulse to ugliness. What this ugliness entails is the residue of an unraveled sense of tradition – so to say, we’ve left everything behind, forgotten everything, that we no longer know how to build. Our libidos were liberated too quickly. We fell victim to originality, that curse of the mediocre and godless. We don’t know a thing of beauty nor how to recover once it has been lost. The sense of today’s ugliness is essentially a failure to locate a secure basis for truth in the face of plurality. Fascism is then better understood as an abreaction, the release of a desire for absolutism, a way back to the beautiful and coherent.

It is only too easy to look to Nietzsche:

“Modernity is characterized by: the abundant development of intermediate forms and the degeneration of pure types; the breaking-up of traditions and schools….”

In Nietzsche’s notebooks we find the ingredients for our antidote, depending on our personal preferences. Our aesthetic impulses have been culled: this is evident. What we require is beauty rediscovered, unbound, a newfound devotion to “pure types” in which we might find greater perfection, a clearer path to the divine.

We cheekily postulated a collective desire to be fascist. And in this we remain confident: when it comes to the conditions under which beauty can be reclaimed, we suggest that everybody desires to be fascist; that is, take beauty seriously. And why shouldn’t this be the case if they, fascists of our era, appear to be the few preoccupied with recovering the conditions for the beautiful?

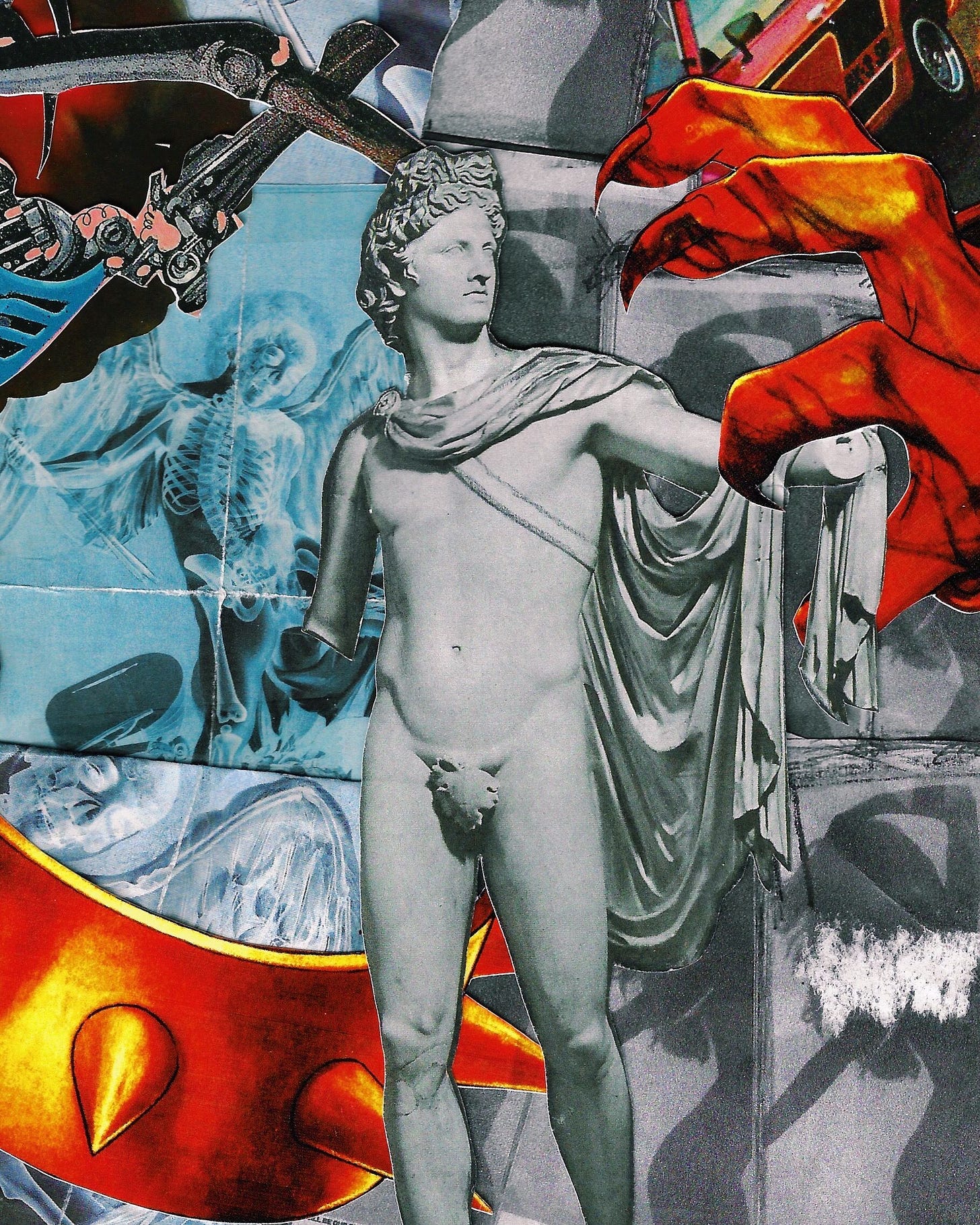

Our Lady of Grace and Derision, Camille Paglia, sees a hierarchy to art; everything is ordered out of Dionysian chaos towards an Apollonian idyll of beauty. The Apollonian is Paglia’s expression of a masculine impulse, which she suggests is exalted by gay men – the homosexual cult of beauty, as we find it in Sexual Personae. The Apollonian ordering of chaos, the origin of art, is for Paglia a militant form that excludes the chaotic; beauty emerges from the Apollonian conquering and ordering of nature’s daemonism as an absolute form decimating moral and ethical concerns. It is without doubt possible to suggest that a Paglian theory of art motivates a fascist sensibility: an exhortation of the Apollonian idyll, and in fascism we see a Faustian supremacy.

This has perhaps mistakenly led some to conceive of a homosexual mode to fascism, as though we observe a distinction between heterosexual and homosexual fascist variants – in reality, there is no such thing. The ‘homofascist’ is mere hysteria, a phantastic political invention. This intrigue is perhaps motivated by the notion that fascism and subjugated groups are incompatible; that queerness is inherently progressive; the liberal delusion that gay men are essentially egalitarian humanists; for whatever reasons, that homosexual desire is revolutionary. Has history not provided enough examples of revolutions preceding in the alternate direction, that is, towards greater forms of tyranny? We must, on the contrary, concede that there are reactive forces of dominion and subjugation existing alongside active forces of distribution.

What we have in Paglia is a veritable Faustian high-priestess, and we, her readers, are neophytes in the Faustian occult. We say: violence is art is sex is order, isn't it? It is as much with Mishima – he anticipates the Paglian doctrine. Mishima’s allure is shrouded in his search for beauty in a dilapidated world, the beauty of militant heroism. Mapplethorpe, too, presents a militant, anti-egalitarian art that views freedom and democracy as incompatible. Beauty is discovered at the height of the Sadean libertine’s intoxication and exercise of absolute domination over his subject, not in the sanitized confines of a liberal safe-space. The fascist stance is appealing only because it presents the Apollonian as the highest ideal. He commands that everything be made beautiful, and nothing less.

The struggle for beauty, for a renewed aesthetic vigor, is taken seriously, perhaps too seriously, by what is commonly misunderstood as the homofascist. We do not suggest that they have a monopoly over the desire to create the beautiful; rather, it is something that emerges as central to their ethos. Forging a Bronze Age Mindset – “Only physical beauty is the foundation for a true higher culture of the mind and spirit [...] Only sun and steel will show you the path.” Is this not the way to a beautiful life?

It is perhaps unsurprising that young men – regardless of their politics – tend to gravitate towards what we’ve poorly understood as the homofascism of figures such as Mishima, Douglas P., and BAP. If Paglia is to be trusted, this drive is prompted by a recognition of the Apollonian in, say, BAP’s rhetoric. Walter Benjamin’s diagnosis: the aestheticization of politics; spectacle and the right to expression. No fundamental changes so long as everything is beautiful. Warhol asks Didion, Why can’t it just be magic all the time?

That there are few figures on the left who promote a recognition of the Apollonian, of an appeal to beauty, is perhaps due to the left’s emphasis on egalitarianism. Such that one should ask: is the left bereft of a genuine aesthetic impulse? Our answer is too obvious to state without incurring ridicule. That is, the left must present a politicization of aesthetics. Yet there are those of us who have long derided certain factions of the left for their blasé disregard in articulating what is beautiful and heroic in our age.

On the contrary, we instead have the valorization of resentful dissimulation under the guise of discourse. We could say, recalling Nietzsche, that it involves a modern intellect which takes itself too seriously in its state of undress. Everything must be taken apart. Our method is deconstructive, highlighting the troublesome effects of given art forms, and has ceased being productive. Disfigure, deconstruct, whatever…the forces of reaction have no capacity for genuine laughter; we charge them with looking at life with twentieth-century eyes.

“Yet why must it be that men always seek out the depths of the abyss? Why must thought [...] concern itself exclusively with vertical descent? Why was it not feasible for thought to change direction and climb vertically up, ever up, towards the surface? Why should the area of the skin, which guarantees a human being's existence in space, be most despised and left to the tender mercies of the senses?”– Is this, too, not an exhortation of a ‘vitalist’ aesthetic?

Some would be content to leave it here. And it is indeed quite an easy hill to die on. We could say, for those of us still on the left, that the Nietzschean vitalists have it right, those true defenders of beauty. They erect a bulwark against lower forms of life (watch them closely), a veritable cure to modern malaise…fascist fitness of body and intellect…vitality of the right-wing…what could this mean? This appeal to heroism and defense of beauty is still-born, dead at the instance of conception. You’ve seen it: left-wing or right-wing, I’m pro-violence. Against the new, we’re being told our only option is returning to prior forms, an appeal to traditionalism. The so-called vitalists, in their reclamation of beauty, reveal an utter lack of imagination. What is needed, rather, is an articulation of the heroic and beautiful in our own age as Baudelaire encourages us to do. There can be no vitalism in reanimated forms; traditionalist calls for a return to absolute beauty are cynical efforts.

They have a corruptive influence, those moral amoralists who attempt to revive Venus’ corpse. It is a cadaver’s waltz. When Mishima’s aged novelist says to his desired inamorato, “Beauty has taken on an exaggerated form, become old-fashioned, and it is either magnificent or a joke…” – is he not piercing arrows in Mishima himself? Are the current appeals to traditionalism and beauty anything other than exaggerated hysterias? How is it that one claims to defend beauty yet fails to recognise any beauty left today? Per your palate, isn’t Mishima either magnificent or a joke, in life and in death? Let those of us with unrefined palates say he was both and be done with it.

And so it remains: what is heroic and beautiful in our own age? We are no longer content with resurrecting past ideals… Retvrn narratives and mediocre appeals to traditionalism bore us. They have Keats and Yeats while we have Wilde. What have we to do with orthodox -ists, -isms and Red revivals? That we’re yet capable of forging a decisive path is evident, but the conditions appear to be ripening. An ever greater possibility for abandoning false pretenses and comprehending the divine perfection of God, or nature, is upon us. There have been glimmers: heterodox Catholicisms, new modernisms, a revaluation of the impulse to novelty with recognition. We call for a necessary contemporaneity adequate to the age, without falling victim to the delusions of a grandiose past and the pessimism of an apocalyptic present. There can only be now, but only as a temporary remedy. How could we possibly return to an absolute, eternal beauty after Baudelaire?

Stanley Bast is a net art propagandist. @camillepawglia

Stanley’s piece is part of Cracks in PoMo’s new venture of featuring guest writers, which you can read more about here. Please consider signing up for a paid subscription to this page for more riveting content. If you’re new to Cracks in Pomo, check out the About page or read up on our Essentials. Also check out our podcast on Spotify, Apple, and YouTube and follow us on Instagram and Twitter.

Check out his piece ‘martyrs of beauty’ in the zine

And check out Stanley’s appearance on Cracks in PoMo the pod here

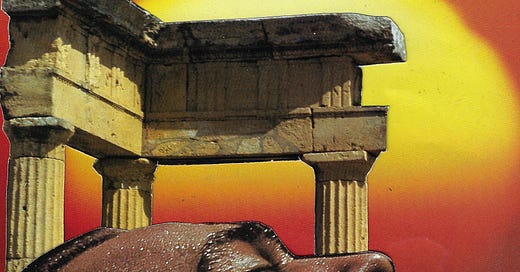

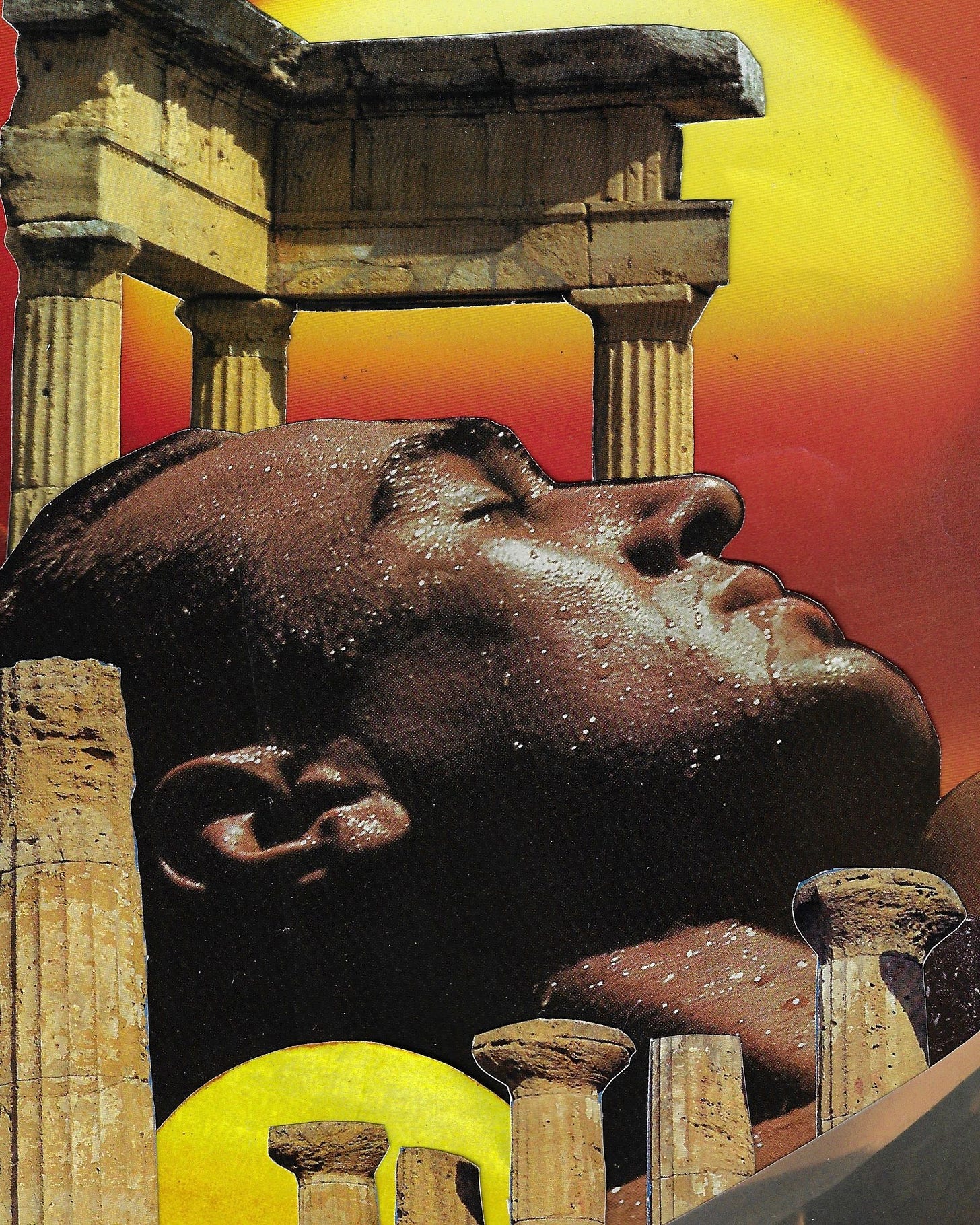

graphics by Patrick Keohane @revolvingstyle