Instantaneous

Mapping the Baudrillardian hellscape through Colombia, Florida, Alabama

“Esse est percipi” (to be is to be portrayed), wrote the Argentine Jorge Luis Borges in his short story A weary man’s utopia, which takes place in a futuristic and rather dystopian world. In this short story, the only relevant reality is that of the image. According to Eudoro Acevedo, the protagonist—as usual, a Borgean alter ego—in the past where he comes from, “images and the printed word were more real than things. People believed only what they could read on the printed page. The principle, means, and end of our singular conception of the world was esse est percipi.” In that sense, everything that exists beyond images is not to be counted as real, as seen in the future that comes to be realized out of the hyperreal utopia of our present.

If you aren’t already subscribed, click here to get a limited time 40% off discount on an annual sub.

To put it in Baudrillard’s terms, everything is now an image without referent, pure sign without an original source. It is, therefore, not a coincidence that, for Baudrillard, Borges was the progenitor of the “universe of simulation,” that point in which the elements of science fiction have been incorporated in our known reality.

This eerily echoes the experience of riding a plane nowadays. As I discovered on my most recent flight with Spirit Airlines from Orlando to Bogotá, just like seats have shrunk, so have windows—as in a world not much unlike Alice in Wonderland’s. Food is no longer served, and the shared experience of an in-flight movie is no longer available. As Ryanair’s CEO recently stated, “I want to get rid of the two toilets at the back of the planes so I can add six extra seats.” All you can hope for is for the experience to end as quickly as possible as you enjoy the cinematic experience of a plane ride on your handheld device.

The plane takes off and passengers scroll through their phones and go over the posts and Instagram stories they had already watched prior to having lost connection with their carriers. I do the same before watching the Cohen brothers’ The Big Lebowski on my iPad—which I manage to hide from the flight attendants in the back of the plane during the scene where they stick The Dude’s head in the toilet—and get the same kick out of rereading posts and rewatching stories.

As I move around in my seat and stretch my legs in the aisle, I catch a glimpse of Barbie and Napoleon on other people’s screens. For a second there, and after several bouts of turbulence, I feel like a passenger in Don DeLillo’s The Silence. I look across the aisle, realizing how much the cinematic experience of the handheld device on a plane ride is so much like that of wearing a facemask, especially for children and the elderly.

We approach Bogotá, the Capital of Colombia, which the proliferation of images over the internet might have you thinking of hot, tropical weather and voluptuous women in shorts and paisa accent like that of Karol G. The pilot welcomes us with his broken English: “overcast weather, 55 degrees Fahrenheit, and scattered showers all throughout the day”—appeasing the curiosity of weather-obsessed Americans.

Once on land, and after minutes of waiting for a crowded bus in the middle of the rain, I begin to feel that sense of proximity that I had been lacking the last couple of months while working on tedious academic work at the U of F in Florida. As I constantly check my pockets to make sure my phone and wallet were still there and I haven’t been pickpocketed, I can feel the anxiety of the past few days begin to dissipate. The third world bus ride was the cure to my overactive mind made worse by academia.

Borges’s main character elaborates a critique of his past world (Borges’s present) by contrasting his view of reality with that of the brave new world that has risen out of a reality made up of printed words and images. In this world, the tall man who welcomes Eudoro explains that “it is not advisable that the human race be too much encouraged,” and, thus, “what is being discussed now is the advantages and disadvantages of the gradual or simultaneous suicide of every person on earth.”

Apart from lecture halls in US grad schools, this is the sort of thought that crosses people’s minds, and which some utter aloud when riding Bogota’s public transportation system: a Malthusian take on life mediated by the internet, being that it’s enough to see photos of overfilled streetcars that were incinerated during the El Bogotazo to know things haven’t changed much.

I spend a whole week in the city, riding the bus the whole time. I saw people getting on and off, street rappers who coined their own words in Spanish to match those of rap lyrics in English. They rapped their rap conciencia about how much the system was after them, about the invisible Big Guy who exploits everyone but the privileged, and about how much they believed in family and God and distrusted the news—poorly rhymed lyrics that tell everyone what they want to hear while getting in return what they want: loose change to buy themselves a bottle of Rey de Reyes (a cheap whiskey to be mixed with orange juice). I can picture Žižek touching his nose and talking about the unspoken words of the Lacanian big Other in this urban transaction that takes place in the large and defective network of public transportation in Bogotá.

Before leaving the city, I find myself in a colonial-style home in the historic part of downtown sipping a beer with two female friends and my best friend during a poetry reading. I catch myself making a dad joke that can only be understood in Spanish. “Yo soy de Chupameestepenco, Guadalajara,” I say to a Mexican girl they just introduced to me. “Yo de Culiacán,” she replies.

The night goes off with a couple of reasonable and earnest lines by the least pretentious poets. We are about to leave for another bar when the Mexican girl gets up all upset. “I know what you meant by Chupameestepenco, Guadalajara,” she says; the three guys she’s with, all poets, approach me, about to poke my eyes out, forgetting all the lure and power of words. “You wanted me to suck your dick; that’s what you meant, trying to act all machito on me.” I utter a couple of incoherent words and exit the place as my two female friends ran down the street after me. My bad joke is turned into a threat to demolish poetry and civilization. We saunter, as Thoreau would have put it, until we get to the bar.

The city–drenched in concrete–inevitably hardens you. As you approach the downtown area with its tall buildings and graffitied walls, the purer and the more realistic the experience gets. If you go to a bar, you can smoke by the entrance with no one complaining. Cigarette butts are scattered all over the sidewalks. Some garbage here and there. A homeless guy might show up from time to time begging for money, a cigarette, or just grabbing cans and glass bottles to exchange for cash.

“I’ve been working at this corner for four years now,” one of them tells me. “I follow the Socratic method: I’m like a gadfly. Now 74, but I have never been sick. I don’t eat much but sleep well. As long as you sleep well, food is secondary.” I tell him I eat well, but my issue is getting a good night’s restful sleep. “Spend time outside, be observant, talk to strangers,” he advises before leaving.

I’m back on a plane. The coffee is instant coffee–it sucks, it’s not free. I go over Instagram stories I collected from the trip. None of them show the scuffle, but I did manage to get a glimpse of the asphalt, the trash, the brick and mortar of the city. It’ll all be gone within a couple of hours.

Now I’m back in Florida. I spend Christmas Eve with the family. We sing villancicos, eat Venezuelan hallacas and Colombian tamales for breakfast. It’s a sort of intra-ethnic culinary competition. The dogs lay on the carpet and sleep. My dad and my uncle spar about Israel-Palestine. The war goes on, streamed in real time over the internet. You can partake in the best course of action if you go on Twitter. You can tell the good guys from the bad if you follow the right people. You can pick your favorite image of horror from the side that grants more social prestige and post it on Instagram. You might feel unsure about having posted it. But oh well…it’ll be gone within 24 hours anyway.

Karla (I’ll show you a picture of her) and I leave on a road trip. We sleep in the car the first night, the local Buc-ee’s. The brisket sandwich is awesome. I grab a couple of souvenirs for my friends that I intentionally forget to pay for. Next morning we drive through Alabama. The mountains shine. We have breakfast in Birmingham. At the museum we discover School of Beauty, School of Culture by Kery James Marshall’s. The setting is a black hair salon with references to Raphael’s School of Athens, and, at the bottom center of the canvas is—as in Holbein’s The Ambassadors—the face of a white, blonde woman. Everyone in the hair salon is so lively–memento vivere–the blonde’s face is gorgeously uncanny.

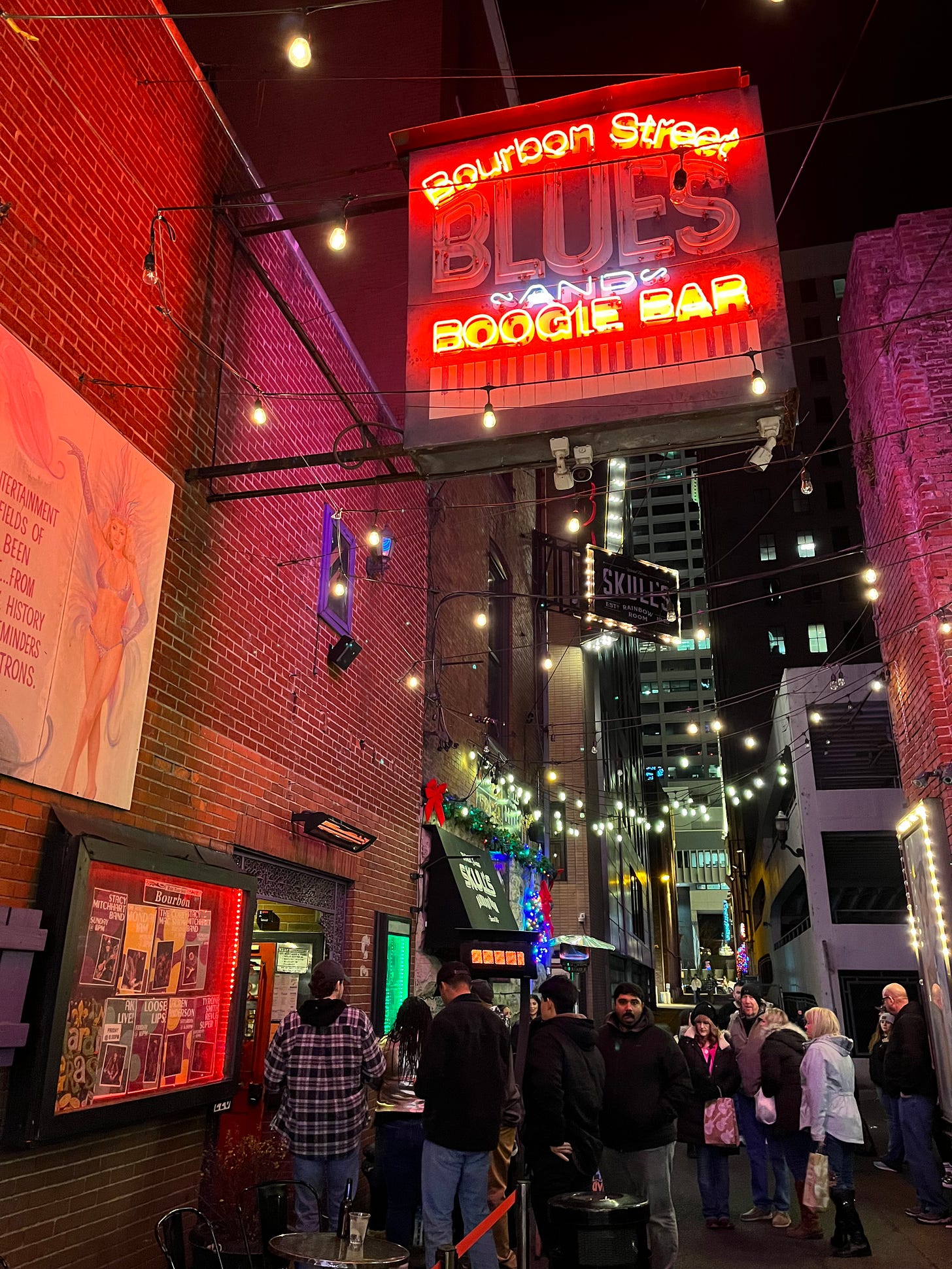

We spend a couple of days in Nashville. We get ourselves a black cowboy hat and eat fried chicken and banana pudding. It’s COLD outside. We end up in Printer’s Alley. There’s a blues/soul band playing. The only white guy is the sax player. He’s in his 70s and looks so gullible and wholesome. The singer is 84 and he’s wearing a Superman costume. I feel like I’m listening to Kerouac’s recording of The San Francisco Scene in my head.

It’s now New Year’s Eve. The town is booming, but we first go to the movies. We watch Poor Things. Rather than thinking of Frankenstein, it deserves to be watched as a contemporary reading of Hesse’s Siddartha—a female Buddha as she learns about life’s ailments and contradictions. Burger and fries and we’re heading to Nashville’s Big Bash. We arrive just in time for Lynyrd Skynyrd and the countdown before the Note Drop. Long beards and a southern drawl as they play their famous hits. Cowboy boots and hats everywhere you look. There’s a couple in front of us. They’re taller than everyone else. Some complain about their height because they’re blocking the view, but at the same time they look so angelic that everyone wants to stare at them, see them line dancing and drinking beer out of their hat crowns. “Let’s go Brandon!” some teenage kid yells from the crowd. Fascists, right? But are we really in the middle of a civil war about to break out? All I feel is my hands freezing and the serene urge to smoke.

We drive back home the next day. As Baudrillard puts it, America is primitive and “driving is a spectacular form of amnesia.” The American freeway as part of nature, a part of the desert like a “gigantic, spontaneous spectacle of automotive traffic. A total collective act, staged by the entire population, twenty-four hours a day.”

We let Spotify algorithmically pick a song, then manually switch to Dylan. “Key West is fine and fair / If you lost your mind, you'll find it there,” sings the Philosopher Pirate. We arrive in Gainesville at 1 am. We get chicken wings and Budweiser before arriving home. “That’s not beer, that’s lager,” a British guy told me once after I quoted Blake at a bar: “Prudence is a rich, ugly, old maid courted by incapacity.”

Please consider signing up for a paid subscription to this page for more riveting content.

If you’re new to Cracks in Pomo, check out the About page or read up on our Essentials. Also check out our podcast on Spotify, Apple, and YouTube and follow us on Instagram and Twitter.

MASA tortilla chips by Ancient Crunch is offering our followers 10% off their order with the promo code CRACKSINPOSTMODERNITY. Click here to redeem.

graphic by Patrick Keohane @revolvingstyle; photos by Juan M. Martinez