Order your copy of the zine vol. iii (feat. work by and ) here.

And RSVP for the launch party on 5/22 (where they’ll both be reading their work) here.

*Disclaimer*

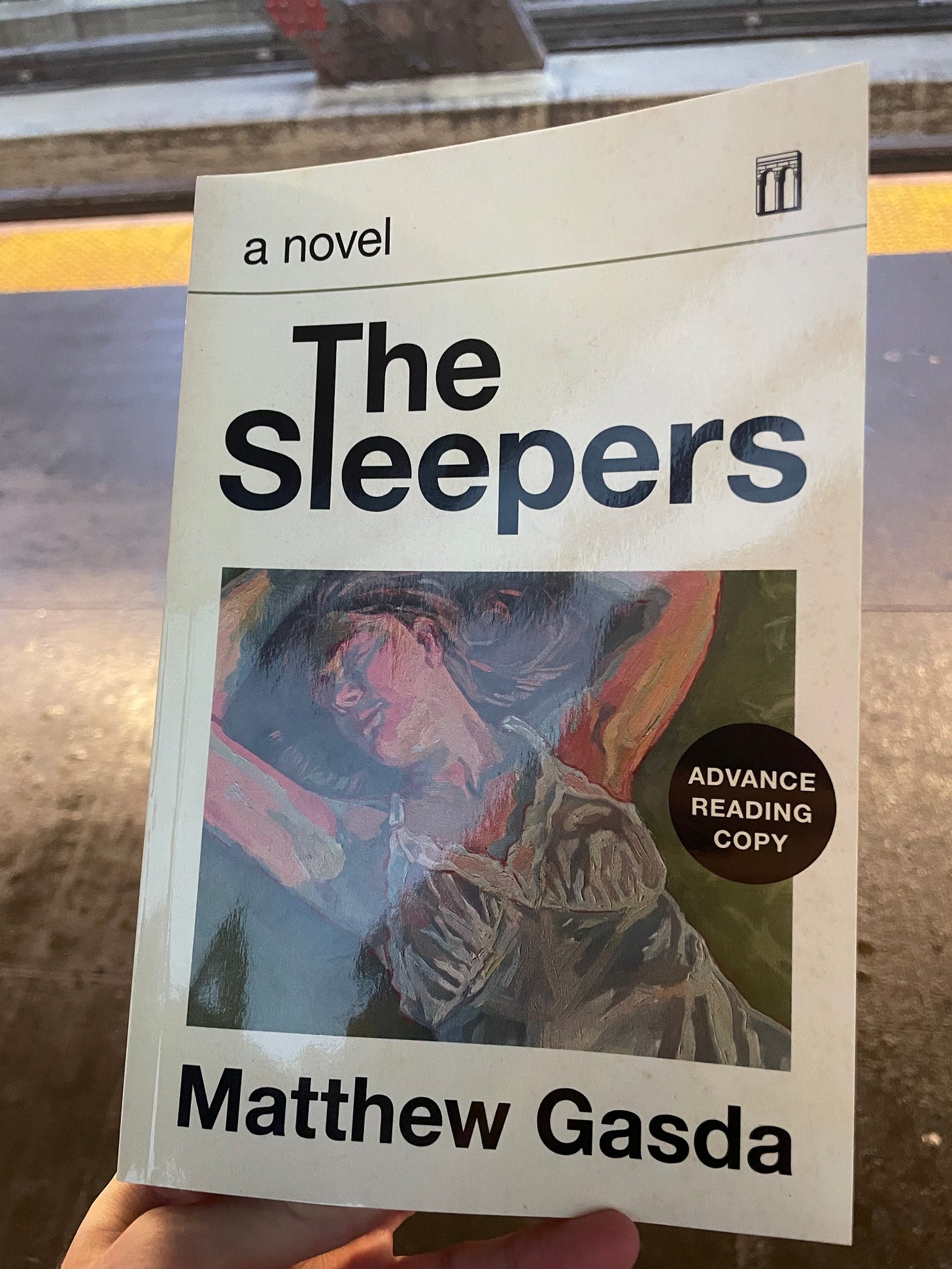

Arcade Press’s advance reviewer copy of Sleepers shouts, in thunderous all-caps surrounded by a heavy-inked black box on the title page, “THIS IS AN UNCORRECTED BOUND GALLEY. PLEASE QUOTE ONLY FROM FINISHED BOOKS.” With all due apology to Arcade Press, I’m gonna have to quote from this still-warm, wet-inked puppy a couple times to give it a maximally faithful review. But they don’t need to worry. Already, at this supposedly uncorrected stage, it looks like a carefully prepared novel. If some of the quotes don’t match their counterparts in the re-corrected and done-up printing, then, well, in Matthew’s own words, as emailed to me back in 2022, “as an artist--i always want my critics as far under the hood as they can stick their heads.”

Is this water?

Gasda’s first novel since his printing-on-the-basement-letterpress-with-his-sister days begins:

Akari decided to walk north along Bedford Avenue instead of switching to

the G train. The fresh air felt good, and it was a beautiful day, so why not?

That “, so why not?” gives us our way in.

Over these last few years, I’ve heard a good number of friends as well as critics decry Gasda’s literary style as “banal realism”—on the one hand, an effort to realize the jouissance of standing in line at the grocer as vaunted by David Foster Wallace in his (in)famous 2005 Kenyon College commencement speech, “This is Water.” And on the other, he’s been accused of collapsing full, human experience into stock characters of lame, pejoratively bourgeois drama-memes that exude contempt for its audience’s emotional complexity and intellectual ability.

That “, so why not?” that tags at the end of Sleepers’s first paragraph seems, at first, fodder for such dismissive readings: The question is redundant to the rest of its sentence, which has already established the half-in-the-character’s-head, half-remote tone that the question tries to drive home. It ostentatiously invites the reader to take part in Akari’s internal (not monologue, but) dialogue—not as an arbiter, but as a participant narratorily nudged toward agreement with her. It sets the novel up to be another wave in the long-rising tide of relatability-porn—the fundamental conceit of that half of autofiction that attempts to describe its supposedly unique author-protagonist in ways the reader will recognize in him-/her-/themself, so that the book is enjoyable, not as a fictional escape, but as an oneiric-onanistic mirror.1

But Gasda’s novel is not exactly that, and its first paragraph’s final tag-question might rather mean…nothing but that “, so why not?” is what Akari thought to herself as she decided not to take the train because the weather was nice, and the narrator reports this without any rhetorical intent beyond that basic reportage.

The same goes for Sleepers’ subsequent winding through episodes of the ennui-poisoned lives of Akari, her sister Mariko, Mariko’s live-in boyfriend Dan, and Akari’s (ex?)-girlfriend Suzanne. There are confused, aimless fights, despairing breakups, awkward dates, eventually a child and parenthood suffused with nostalgia-capped melancholy. The tone of that opening “, so why not?” never abates: Sleepers taps, in meticulous cycles, the inner lives of one character after another, as though the narrator is searching, just as desperately as any of the characters, for some final epiphany, some direction, some clear significance.

So this novel carves a strange diagonal across the otherwise parallel-row-ploughed field of banal-realistic autofiction: Gasda is not writing about himself. He shares a simplified style and certain standard conceits with autofiction, sure—the characters’ neurotic self-observation, the minute description of quotidian actions, etc.—but achieves a subtly different form and effect. To describe that effect accurately, though, I’ve got to run us back a couple centuries.

The Biedermeier Period

In the 1850s, lawyer Ludwig Eichrodt and doctor Adolf Kußmaul2 started publishing poems under the pseudonym “Gottlieb Biedermeier,” largely parodies of the poetry of small-town schoolteacher Samuel Sauter and of the staid, “kleingeistig” (small-spirited) provincial bourgeoisie he represented. Eventually that pseudosurname, “Biedermeier,” became shorthand for the literature written in German-speaking regions (there was not yet, alas or hallelujah, a Germany) from 1815’s Vienna Congress, in which, after Napoleon’s fall, Austrian Prince Klemens von Metternich attempted to restore Europe’s old monarchies to divine legitimacy, until 1848’s bourgeois revolution, which opposed the old monarchies’ restoration in favor of democracies.

The literature of that period, limited by harsh censorship of political speech on behalf of the newly restored (and rightly paranoid) royals, generally reacted to said censorship by constraining its scope to the small worlds and constricted experiences of the authors or, in any case, their petit bourgeois characters: the small-spirit conflicts of profession, social standing, and internality of a class whose only ambition was “ambition.” Around the same time, French revolutionaries were reprinting pieces of the Marquis de Sade’s Philosophy in the Bedroom as non-fictional political tracts.

Thus autofiction as we know it—in both its relatability-pornographic and voyeuristic modes—was born, and then, like all children, was ridiculed until it learned to be anxious. Now, looking back at the Biedermeier through the distorting lenses of its parodists and successors, it all looks like earnestness and parody and claustrophobic horror. In the same way, looking at recent autofiction from the vantage of those who can use that word (that is, in hindsight), we have to see, say, Megan Nolan and Sean Thor Conroe, in terms of the same mixture: They’re writing themselves while parodying themselves and the very notion of their autochronicles—even if, at the time of writing, they had no such intention.

But Gasda does a different thing, one that doesn’t exactly escape from that earnest-parody-horror complex occupied by the Biedermeier writers and their descendants in current autofiction, but one which does diverge from them by presenting its surface-realism as purely fictional. Far from the autofictional root-notion that a writer may only write from lived experience, and its ethical and political corollary that writers must not write about experiences that they (or people who superficially resemble them) haven’t lived, Gasda begins writing from a perspective that, on the shallow identitarian Venn diagram, he cannot have had—that of a shakily lesbian Japanese-American woman from the West Coast—and presents her perspective in terms of the same internal mode as autofiction. As Ludwig Eichrodt and Adolf Kußmaul ridiculed their pseudonym, Mr. Biedermeier, by writing just as his real-life counterparts did, Gasda critiques autofiction by applying its stylistic hallmarks to a story that violates its most basic tenets.

Internal Reverie Service

Our brief look into Akari’s life is no less earnest, parodical, and horrifying for the necessary degree of distance Gasda must hold from her. Same goes for the novel’s succeeding focalizers: Mariko, Dan, Suzanne. Gasda writes the same ultra-internal, hyper-detailed narrative for and from each, often spiraling off into self-auditing, but also universalizing, series of questions like (from Akari’s opening section),

Was there a difference between sensuality and narcissism? Was there

a way to revel in the sensual presence of another person without giving

the ego too much of what it wanted? Was it possible to lust after Suzanne

without seeing her as a good to be consumed?

These question-chains, at first glance, seem to plant an authorial ethics on top of Akari, turning her into a pawn for some sort of moral propaganda masked as fiction. But after each such detour, Akari’s narrative returns to immediate sensations—whether she’s actually hungry when she wanders into a restaurant in Brooklyn, what she’s feeling as she walks sleep-deprived to Mariko and Dan’s apartment—and then italicized digital conversations with her ex-girlfriend and various dating-app matches.

That is, what seems like stale propagandizing (or, read from another angle, bitter ridicule) shows itself to be Akari’s own ethical self-audit and is then dwarfed by avalanches of banal, neurotic detail of her thoroughly uninteresting situation—which, then, by sheer persistence, becomes horror.

Enumerating every tiny detail, in turns, of Akari’s, Mariko’s, Dan’s, Suzanne’s unremarkable days and their anxious, relentless self-auditing, Gasda’s novel reads like a disinterested report from some Internal Reverie Service. Gasda’s is not a classic third-person limited narrator, but an omniscient narrator with an excruciatingly eidetic memory who is horrifically limited by the small-spiritedness of the characters Gasda has doomed it to narrate.

This is a double-decker horror: On one level, the characters themselves are so thoroughly trapped in stifling habit and moralizing reflection that their internal lives read like the futile, confused twitches of a dog whose master has locked him in a crate so small he can’t turn to chase his tail. From a higher vantage, the narrator’s prodigious capacity for detail and clarity, applied to such limited subjects, is like that master who, though the crate is locked, can’t bring himself to leave the room, for fear the dog will somehow escape and get hurt.

There is an absurdity in that image that has no counterpart in the novel, an absurdity made impossible by the helpless earnestness of the characters’ internal squirmings. The ideas of hope, aspiration, longing cannot exist in these characters’ narrative crate. The best they can reach for is not even escape or relief, but consolation, the comfort of the tail in the mouth—an exciting text message, an interesting sexual affair, an abstract thought that finally convinces them that they are in fact superior to what they thought they were, eating food and finding that they were actually hungry this time—which might, for a moment, allow them to forget the lock on the crate’s door. Each of Gasda’s Sleepers might easily produce, through the narrator’s ink, the line, “There is significance, but not for us,” then feel numbly guilty for thinking it and open Tinder so as not to see what bleaker thought might follow. Akari’s on-off lover Suzanne comes close, near the novel’s end:

All Suzanne can think about [...] is how ridiculously, stupidly ordinary, repeatable, universal, and human the scene is . . . how it’s happened billions of times before, and will happen a billion times in the future. She wonders if this is not the most significant thing: the sameness of people.

She doesn’t really wanna think about it.

If the dog were to think too hard on life outside the crate, he might quit chasing his tail and start biting at the door’s thick wires, which he knows would accomplish nothing but some ruined teeth. Likewise, Suzanne, here, casts herself as the cosmic-horror protagonista who turns back, on threat of certain madness, from consideration of eldritch terrors beyond her comprehension. But while Lovecraft draws his fear from impossibilities, Gasda draws his from and into the possible—and, further, into the common and the inevitable. For his Sleepers, anything at all becomes a cosmic horror when seen and contemplated from the right angle, so even horror becomes so banal as to ward off mention. Lovecraft’s hero scrambles, wide-eyed and shrieking, from the cyclopean cave of unearthly geometry; Gasda’s characters roll their eyes and slouch on. If they don’t, the narrator’s Internal Reverie Service might back-audit and fine them.

In the end, Sleepers is, on its surface, precisely a sleepy novel: Nothing happens that one might not see in the course of a normal few weeks, no one thinks anything that’s far enough from cliché to assert a clear distance, and no character is particularly worth caring about. But the very relentlessness of the novel’s description, with such subject matter to describe, evokes a harsh, strident sense of horror that sneeringly indicts on charges of crimes against the humanities the very realist and autofictional modes from which Gasda draws his style.

Jonah Howell writes and teaches literature in New York. His play Lillita and the Tramp will open in May at the Hudson Guild Theatre.

The other half of autofiction, with author-protagonists who actually are unique, tends rather toward voyeurism. Note that I observe neither that relatability-porn nor this voyeurism as bad things, but simply as the dominant strains in a new literary genre which any given reader may enjoy or not, with no moral implications either way—though the ability to enjoy is always better, for any given reader. Pickiness is far overrated.

Etymologically, Ludwig Oak-red and Adolf Kissy-face. I append no further comment.

I finished the book a week or 2 ago

The Akari - Suzanne bits seemed wholly unnecessary

Like a deflection from the main story, or maybe they shouldve been combined into one POV

The last chapter reveal felt good but perhaps stronger with bookends from Akari