The Postlib Corrido Cosmology

Los Corridos, a form of Mexican Norteña music, has been on the rise in the United States. The popularity of the genre has reached beyond the diaspora and into the Latin American community at large, resulting in chart-topping songs that penetrate the mainstream. Peso Pluma, the most emblematic success story in the genre’s history, performed on the Jimmy Fallon Show, America’s rigor mortis-grinning arbiter of pop culture.

Corridos are nothing new. Their roots originate from the admixture of German and Polish migrants to Northern Mexico in the 18th century. With tubas, accordions, and a yodelling vocal style, it is a close cousin to the Bohemian polka. However, the lyrical content of this new corrido, often called “corridos bélicos” (fighting ditties) is what is worth taking note of. The most popular new artists, such as Peso Pluma, Chino Pacas, Eladio Carrion, and Fuerza Regida, are overwhelmingly young and overwhelmingly cartel-affiliated.

From now until 1/1/24, you can get 65% off a yearly sub! Click here for deets. You can also gift people a subscription, and can get a discount for referrals (1 month free for 2 referrals, 3 for 4, 6 for 7).

When surveying their music videos, for example, Chino Pacas’s ‘El Gordo Trae el Mando’ (The Fat Guy is in Charge), it can strike a gringo observer as almost absurd that the music, with its gleeful tubas and twanging guitars, is being produced by balaclava-clad youths brandishing Glocks from the back of Raptors and F-150s. But among the less explored aspects of Corrido culture are its immersion in the Catholic religious and aesthetic imagination, and the challenge it presents to the Western neoliberal political paradigm.

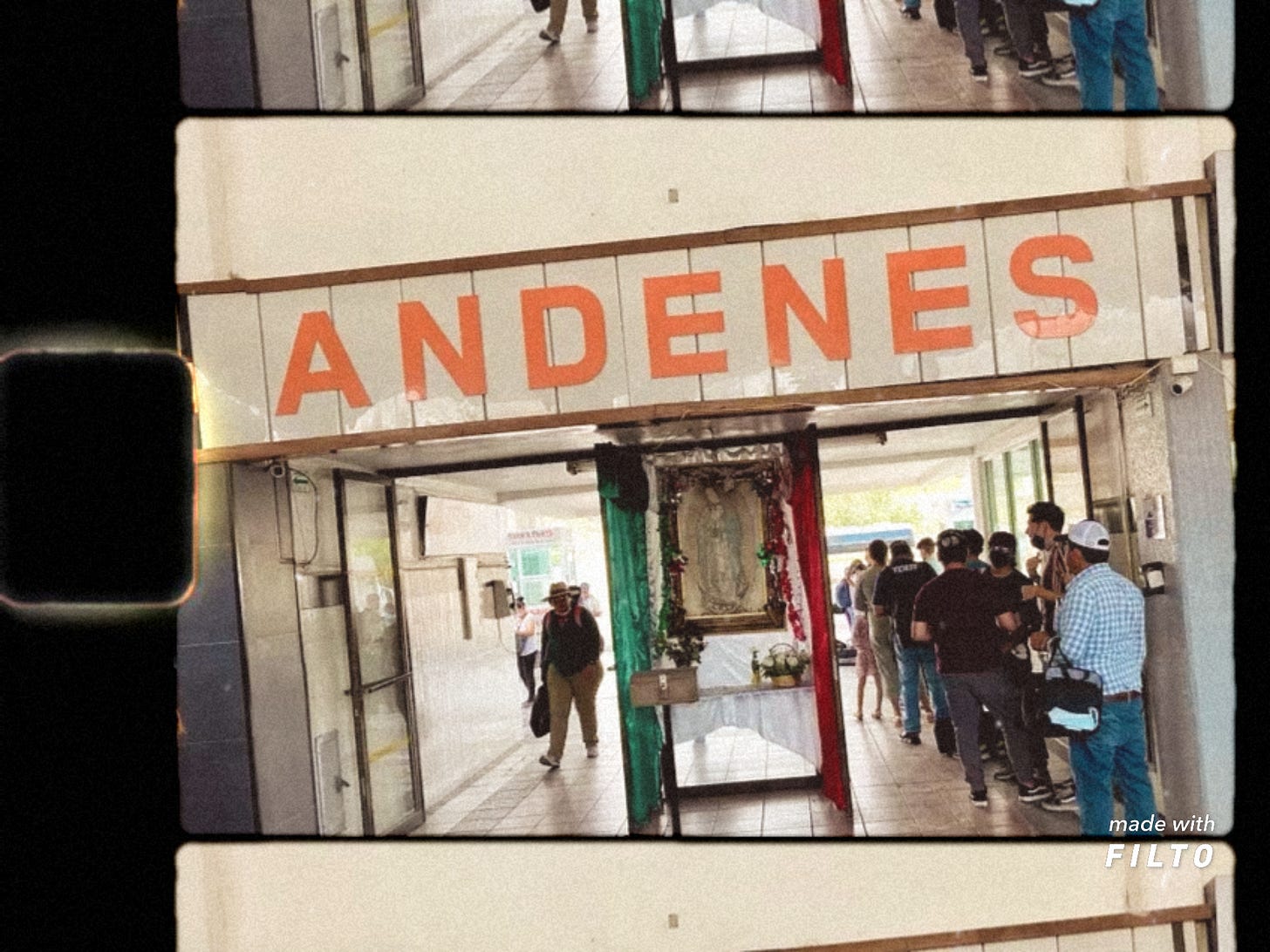

DISSONANT RELIGIOUS IMAGERY

One will also notice the presence of religious motifs, specifically pertaining to the Catholic faith, within these narco ballads. The lyrics often present what some might perceive as a stark contradiction: boasting of successful drug deals, deliveries of packs of weed, cocaine, and heroin, bales of greenbacks, firefights and murders, the opulent materialist life (also found in—and perhaps deriving inspiration from—American hip-hop culture)—and reverence for the Catholic faith, including mentions of scapulars and divine protection from above. Peso Pluma sings in ‘Rubicon’ (rather than a reference to Caesar’s fateful decision, it refers to the popular Jeep model):

‘They say that I’m pretentious, and also an asshole/ I don’t pay them attention, and even less believe them/ I don’t suffer from conscience, I take care of my own hide/ My instincts activate with a good drink’

This idea of not suffering from conscience is a constant within the corrido, after boasting of dominance, violence, and kidnapping, the singer will double down. And yet the next stanza:

‘Standing by on my cell phone and social media/ So that there aren’t problems in this territory/ I wander, well protected from up there in heaven/ You got ahead of yourself brother, we’ll see about that later’

Peso Pluma is coordinating his operation, and he’s convinced this position is ordained by God. He sings of an underling who is too big for his britches, and ominously indicates there could be consequences. Now the third:

‘All that remains for me here are what I bring, hanging/ I’ve got few friendships left by my side/ My necklaces on my chest protect me/ Warding off envy and traitors’

We’re presented with an image of an unrepentant gangster, proud of his achievements in the brutal world of narco manufacturing and distribution, suffering from false friendships and an inability to trust those closest to him, but with an unshakable faith in the religious medals and their symbolism to protect him. We also see this trope in ‘Negro Como la Pantera’ by Chino Pacas and Grupo 24:

‘And he shoulders his rifle/ Across his scapular which protects him from hell/ He’s bringing four mad bastards in the seats/ They’re baring their chests and ready for a firefight’1

Despite the imminent violence, likely ignoble, the scapular is seen as an ironclad protection against the chance of hell. Similarly, in another song from the same album as Rubicon, ‘77’, Eladio Carrión sings:

‘I don’t call the connection, I am the connection/ I don’t have to trust anyone if I have my Glock/ I have no fear, some time ago it was put away’2

NIETZSCHEAN UNDERTONES

Such an anesthetized mindset—the denial of fear and comfort with violence—is reminiscent of Klaus Theweleit’s Male Fantasies. The male soldier, especially under fascist regimes, must deaden all feeling and reject all emotion, and take up his right and duty to clean or purify their land of enemies.

In ‘Mi Terre CLN’ by Fuerza Regida and Juanpa Salazar:

‘Defending that cartel/ The M60 is hanging off me/ Cleaning all that which/ Wants to dirty our lands’3

He must take up the task of ‘cleaning up’ after what is perceived as degeneracy by any means necessary. The ‘freezing up’ or ‘paralysis’ preceding acts of violence described by Theweleit corresponds to the Christian notion of ‘hardening one’s heart’, that is, choosing to cynically embrace callousness in the face of the pain and suffering.

‘Entre lo Bueno y lo Malo’, by Grupo Diez 4to, on the other hand, more truthfully portrays the complex moral conundrum of the narco:

Money brings problems if you don't know how to control it/ This is the story of a narco whose life has changed those of many/ Like some, he comes from the bottom/ In a hurry he started to grow/ Now he’s got many men/ In the neighborhood slinging

He started off washing cars/ He didn’t like books/ His children were barefoot/ He didn’t make enough to even change it/ He began to despair/ He began to change necessity/ Things were coming hard and fast/ Little by little he scaled up

The DEA hasn’t rested/ They wanna see him 6’ under/ But he’s still in charge/ The bills keep circulating/ The envy is overflowing/ You have to eat in silence/ This is what happens when you get promoted quickly

And within the herd you’ll see him with his boys/ And you’ll see that they have really changed/ And with guns always at their sides/ Because death wanders freely/ I already know they want his head/ His blunts never make him fall asleep/ Only mother can get close to him4

The especially poignant line ‘la necesidad lo fue cambiando’ has an essentially Nietzschean metaphysical formulation: quite literally changing necessity through sheer force of will. The title (which translates to ‘between good and evil’, an almost verbatim reference to Nietzsche) and lyrics describes the role poverty plays in the narco lifestyle as well as the conscious choice to escape conditions by exerting one’s will power. However, one of the lines from the second verse goes:

‘The dogs keep barking, they never know when to keep quiet/That's why we keep winning/ There is a God who is listening to us’5

Despite assuming his actions as his own, nonetheless, all is attributed, ultimately, to God.

Corridos offer a sober, and maybe even cynical, understanding of the evils of this world, a lucidity about our participation therein. Its popularity in the United States is a symptom of the aesthetic and cultural expansion of our southerly neighbor as we plunge headlong into a baroque, chaotic era. Although the general trend of a Latinization of the United States is one which brings much needed culture and forms of life for metabolizing our period of decline, the corrideros who express little remorse for their lionization of violence is alarming, to say the least.

SOUNDTRACK OF NEOLIBERAL RESISTANCE?

Of course narco culture, and the primacy of cartels as small fiefdoms which act as the de facto governors of many of the territories of Mexico, can be directly traced back to the escalation of the war on drugs by the United States as a condition for Mexico to join NAFTA. Often, because the cartels are capable of providing public goods which the state is not, they are seen as more legitimate and more trustworthy.

The religious imagination present in corridos can be said to have positively inspired resistance against neoliberal monocrop mandates and opportunistic farmers. This is most evident in the spirituality of the Zapatistas of Chiapas, who aimed to preserve pre-Colombian farming practices that gave agency to local communities. But it also can be said to give justification to cartels, who depend on a constant stream of sacrificed human blood.

The idea that Christ smiles upon a gangster who boasts ‘no sufro de conciencia, yo cuido mi cuero’ is, needless to say, problematic. Naturally, as is the case in the world of US hip-hop, the extent to which Peso Pluma and other singers are directly involved in the crimes they extol is unverifiable. But the constant references to the Sinoloan Cartel imply a level of proximity which would doubtfully be aired publicly unless at least tacitly permitted.

Ironically, Peso Pluma’s name translates to “I weigh the feather,” an apparent reference to the ancient Egyptian eschatological belief that in the ordeal after death, preceding the afterlife, the soul of the deceased would be weighed against that of a feather to determine its preservation or destruction. I myself find the genre a joy to listen to, it makes one “bien empecherado”, is infectious, causing riotous dancing and jubilation.

Perhaps we can infer from the recent rapid expansion of cartel manufacturing and distribution operations this side of the border that a believing narco is dearer to Christ than a faithless government. But one thing is clear: without repentance, the soul of a narco weighs much more than a feather.

THE ENCHANTED NARCO COSMOLOGY

These themes’ coexistence with religious imagery and belief in a higher good may rub puritanically minded Americans as a sign of hypocrisy—or in the least, of cognitive dissonance. Are these corrideros “appropriating” religious imagery to justify their self-serving lifestyles? Are are they perhaps “confused” about the “true” teachings of Christianity. Such a simplistic conception of religion conceals an unimaginative, dualistic prejudice that deeply misunderstands the nuanced and richly textured fabric that is Mexican religiosity.

The Middle Ages, writes theologian Luigi Giussani, was pervaded by “a widespread religious culture, where men were helped to grasp the fact that the religious sense coincides with man's interest in the whole meaning of his life, that the reality of God is the origin of his human personality and the determining factor in his evolution.” This point, argue Giussani, explain “some apparently contradictory phenomena,” listing examples like “religiosity as a declaration of peace (Franciscanism) and religion as a pretext for wars (the Crusades); the exaltation of one's fellow man as freedom in the face of the infinite and the attempt to bend man's will with violence (the Inquisition).”

He goes on to offer an imaginary situation that further fleshes out his assertion:

“there are four thugs in the pay of a certain petty lord who has ordered them to kidnap a nun from a convent. It would not be unlikely if the narrator of this lamentable tale were to tell us that the four thugs said a ‘Hail Mary’ before they set out, in the hope of pulling off the job successfully…On one hand, there is a principle that is quite right–the sign of a truth the social framework recognizes–that God is Lord of everything. Evidently, however, this principle was wrongly applied, not because God could be appealed to at all times only on devout occasions, but because we cannot ask for God's help in carrying out an objectively evil act.”

Corridos are a modern day embodiment of this pre-modern “enchanted” worldview which–though rife with paradoxes–contains more metaphysical depth than the misguided neognosticism and freemasonic utopianism that molded the United States.

Serge Gruzinski, a French sociologist, has deeply analyzed the culture of imagery of the colonization of the New World, especially of Mexico. The pre-Colombian cultures already possessed a theology of the image, and with the missionaries, gunpowder, and smallpox came Christian iconography and forms of piety. The replacement of one religion with another is hardly ever seamless, and despite the best and most brutal efforts of the Holy Office, the Maya and other indigenous cosmologies (already in many ways prefiguring Christian theology, from blood sacrifice, to the sacred nature of the heart) have remained dormant just beneath the surface of Guadalupan Catholicism.

And for this reason, I personally welcome the influence of Latin Catholic culture. This juxtaposition and syncretism of the malign, almost pagan celebration of violence, greed, and power, alongside the faith in the apostolic Church, and Jesus Christ as liberator of the sinful, and dread judge of the world, is more honest than the Protestant moralism of the United States, with its pseudo-prudish pearl-clutching, false consciousness, and prosperity gospel.

Though far from being sinless, the narco cosmology is more true to the essential truths presented in the Gospels: that God is Lord of the Universe, and Satan is prince of this World. Corrideros may not all be saints. Their songs may glorify actions that contradict the ideals of the Gospel. But to write off their religiosity as “false” or “impure” is to ignore the sincere humanity, and the depth of heart from which their songs emerge.

Please consider signing up for a paid subscription to this page for more riveting content. If you’re new to Cracks in Pomo, check out the About page or read up on our Essentials. Also check out our podcast on Spotify, Apple, and YouTube and follow us on Instagram and Twitter.

MASA tortilla chips by Ancient Crunch is offering our followers 10% off their order with the promo code CRACKSINPOSTMODERNITY. Click here to redeem.

graphics made on filto

Y carga su cuerno

Tras su escapulario que lo cuida del infierno

Trae a cuatro vatos bien locos en los asientos

Van empecherados y están listos pa'l refuego

Yo no llamo a la conexión, si la cone soy yo

No tengo que confiar en nadie si tengo mi Glock

No tengo miedo, hace tiеmpo se engavetó

Defendiendo aquel cartel

Colgado el M60

Limpiando de todo el que

Quiera ensuciar nuestras tierras

El dinero te trae problemas si no sabes controlarlo

Esta es la historia de un narco que la vida muchos ha cambiado

Como algunos, él viene de abajo

En putiza él se fue agrandando

Ahora trae muchos muchachos

En el barrio va zumbando

Empezó lavando carros

Los libros no le gustaron

Tenía a sus hijos descalzos

No alcanzaba para ni cambiarlos

Él se fue desesperando

La necesidad lo fue cambiando

Las cosas se fueron dando

Poco a poco fue escalando

La DEA no ha descansado

Le quiere dar para abajo

Pero aún sigue mandando

Los billetes siguen circulando

Las envidias van sobrando

Hay que comеr siempre callado

Esto pasa cuando andas subiendo rápido dе rango

Y entre la manada lo verán con sus muchachos

Y los verán bien cambiados

Y las armas siempre por un lado

Porque la muerte anda suelta

Ya sé que quieren su cabeza

Sus gallos nunca se le duerman

Pura madre que se le acercan

Los perros siguen ladrando, nunca saben estar callados/Por eso seguimos ganando/Hay un Dios que nos va escuchando